What’s that in your pocket? Magic or art? The near ubiquitous iPhone may be rammed with very new technology, but it is a witness of very old, even mysterious, values. Few of us understand its inner workings, even as we indulge ourselves daily with its impressive powers to astonish.

‘My life,’ Daniel Harris wrote in Cute, Quaint and Hungry, his witty critique of consumerism, ‘is suspended above an abyss of ignorance. Virtually nothing I own makes sense to me.’ This is a familiar feeling. If we had to start over, few of us would know how to light a fire, still less design and manufacture a beautiful smartphone.

If civilisations are remembered by their most significant artefact, the iPhone is our memorial. Arthur C. Clarke once said that ‘any technology sufficiently advanced is indistinguishable from magic’. I asked Jony (since May, Sir Jonathan) Ive, Apple’s vice-president of design, if he was familiar with this idea when he was developing the iPhone in a secret Californian wizard’s den. ‘Absolutely!’ he said. Today we have science fiction as reality.

Technology may confer on the iPhone its magical powers, but old-fashioned art is at least as important in creating its ineluctable consumer appeal, a force so strong it turns phone users into delirious acolytes and evangelical supplicants. And this art was the subject of the recent legal stand-off between Apple and Samsung. The distinctive rectangular shape of the iPhone, with its carefully radiused edges, was one of the patents that Samsung infringed.

The Apple–Samsung trial will be remembered as one of the most significant in recent business (and, indeed, art) history. Nine jurors in San Jose heard a month of evidence which required them to make a fine judgment about where respectful inspiration ends and ruthless plagiarism begins.

Compared with the $2.5 billion Apple claimed (and won) for the theft of its designs, the clumsy and irrelevant van Meegeren–Vermeer forgeries that came to trial in 1947 seem trivial and slight: it is estimated that a mere $30 million was conned from buyers by van Meegeren’s ham-fisted counterfeits. Compare this with Samsung’s 2012 Q2 sales of $5.9 billion from machines inspired by Apple’s example.

Fierce nationalist loyalties were excited during and after the trial. According to the New York Times’s David Pogue, Samsung cynically ‘ripped off’ Apple’s design. Meanwhile, a South Korean blogger argued that Apple was absurdly attempting to protect a simple rectangle with rounded corners, a ‘design’ that was surely within the public domain. The blogger continued: ‘If Apple had first made a car with wheels, we wouldn’t be able to make a car with round wheels!’.

What transcends the terms of a debate whose clarity is occluded by issues of protectionism and competitive advantage is the sheer physical beauty of the products Jony Ive has designed for Apple. Voltaire said it was the business of art to improve on Nature. So it is the business of design to improve on industry. This Ive has done. There were smartphones before Apple’s, but they were all clunkers.

The iPhone’s gorgeous shape is deceptively simple. It is a simplicity that has been very hard-won, a proportional masterpiece achieved only after a lot of trial and error. Its textures are deliberately gorgeous. The effect is an understated product that wins universal admiration.

Ive has developed a persuasive personal aesthetic of Zen-like intensity. He gives to any design project ‘effort and care beyond what is necessary’. He has a passionate engagement with materials: an element of an iPhone’s beauty arises from its designer’s perfect understanding of exactly how far you can go with aluminium and glass and how best you might bond these two inimical materials. These are technical problems that Donatello would have understood.

I once asked Ive if a designer could ever achieve perfection. He told me very crisply, ‘You can reach a point where you cannot use resources any better.’ Ive likes to speak of the ‘local maximum’. That’s what’s in your pocket. An iPhone might not be a work of art, but it usurps many of art’s effects. Not least, its power to move people. So the Apple–Samsung trial was not only about money, it was also about genius, creativity, tradition, authorship and provenance. All the stuff of art.

The only surprise, at least to me, was that no one in the courtroom mentioned Jean Seznec’s 1940 study La Survivance des dieux antiques (The Survival of the Pagan Gods). This was a classic of art history whose argument hinged on the important question: ‘revival or survival?’. Seznec argued that the pagan gods were never actually driven out of Christian art, they just adopted certain disguises.

It is exactly the same with Apple design which, in fact, represents a tradition, not a revolution. Jony Ive (born Chingford, 1967) fully acknowledges his own debt to Dieter Rams (born Wiesbaden, 1932). The gorgeous purity of the iPhone was itself inspired by the astonishingly pure, geometrically based designs which, beginning in the Fifties, Rams created for Frankfurt’s Braun electrical company.

A student of Ulm’s Hochschule für Gestaltung, itself a postwar revival of the famous Bauhaus, Rams perfected the aesthetics of restraint, of paring down his cabinets for Braun’s radios and tape-recorders until they were little more than a solid graphic. He still likes to say ‘Weniger, aber besser’ (Less, but more). Rams was trained as a cabinet-maker, not a philosopher, but his achievement was to bring the essential beauty of Platonic form to the production line.

But Rams himself owed something to an older German tradition. The architect Heinrich Tessenow built under the motto: ‘Das Einfache is nicht immer das Beste, aber das Beste ist immer einfach’ (Simple is not always best, but the best is always simple). And this austere aesthetic is itself based on the German pedagogic tradition of Froebel and Pestalozzi, of the nursery building blocks and the Kindergarten, who insisted that understanding fundamental geometrical shapes was an essential part not just of art education, but of all education.

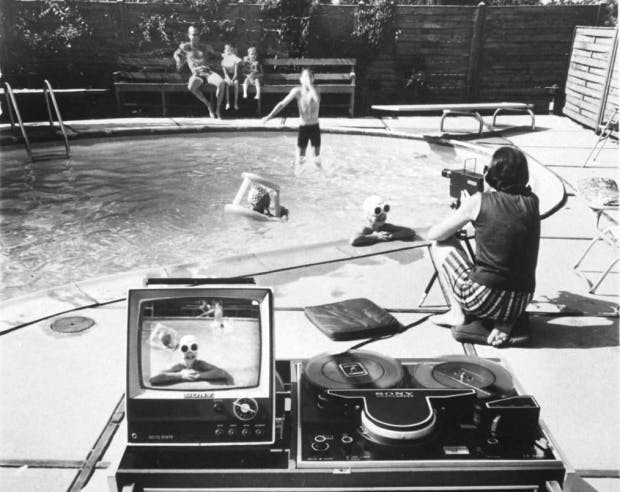

Long before Samsung aped Apple, Sony, the Apple of its day, was aping Dieter Rams and his infatuation with severe geometry. Designs of Rams shown at trade fairs in Germany in the Sixties were the inspiration for Sony’s own impressive range of purist electrical and electronic appliances. And here you find another link. Circa 1980, Sony’s Trinitron televisions were the ultimate expression of what was later called Minimalism. They were the work of Hartmut Esslinger, the independent German designer who, in 1984, shaped Apple’s own revolutionary Mac.

Is this all a story of cynical theft and plagiarism or one of polite borrowing, tradition and survival? Two things are certain. First, the San Jose ruling will force Apple’s competitors to innovate: aesthetic repetition is not a future option because a tradition has been put to the forensic sword. Second, where public interest is concerned, the torments and achievements of contemporary designers make the torments and achievements of contemporary artists appear thin stuff in comparison.

Apple’s address in Cupertino is Infinite Loop. An ‘infinite loop’ is computer language for a never-ending message, technically an ‘impossible termination condition’. Will the ancient design gods who brought us so much magic and art be terminated or reinforced by this patent trial? We shall see when we next visit an Apple Store.

The post Science fiction as reality appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in