London

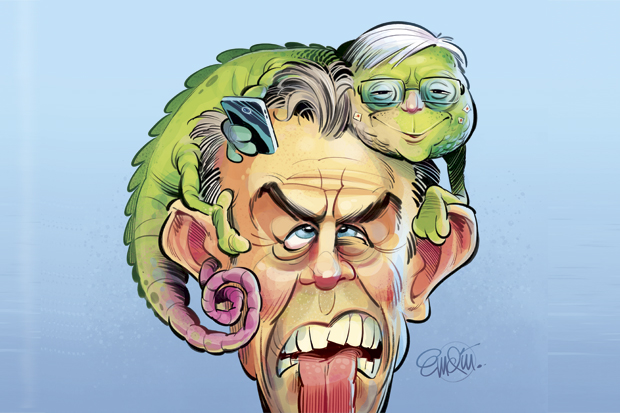

There is something alarming, and distressing, for any sensitive Pom watching from afar your general election campaign. It is the similarity between Kevin Rudd and our own former prime minister Tony Blair: though Blair won three general elections, two of them by landslides and the third by a handsome margin, something Rudd will do only in his dreams.

In Britain, Rudd further distances himself from Blair (who, for all his many faults, was a consummate politician) because of the two things for which he is famous on this side of the planet: eating his earwax and politically assassinating his successor. Blair preferred to eat Italian, and it was his successor who dementedly spent years trying to assassinate him. However, beyond such questions of scale, there are similarities.

In most civilised western democracies there is an acceptance of capitalism and the importance of the prosperity it brings. Blair was, and is, fully signed up to the creed, at least where he himself is concerned — reports of the wealth he has amassed in the six years since he left office usually deal in tens of millions of pounds. In his first election campaign, in 1997, Blair appeared to have bought Britain’s Thatcherite consensus lock, stock and barrel. He promised to maintain the outgoing Tory government’s spending plans for the first two years, and not to raise income taxes. However, thereafter the brakes on spending came off, and a variety of ‘stealth tax’ rises — on anything other than income tax — defined his premiership.

A number of other policies turned out not to be quite as they had been imagined. Blair promised that devolving many central government powers to a national parliament in Scotland would not lead to the break-up of the United Kingdom. However, the nationalist party is in power there, and in a year’s time is holding a referendum on independence. He pursued policies to counteract so-called man-made climate change, but never told the electorate how this would drive up the price of energy and make us a less productive and competitive nation. And he turned a blind eye to large-scale immigration from Eastern Europe, which colleagues of his openly rejoiced in as changing the social face of Britain, but which has caused massive community tensions and has demoralised many of Labour’s own constituency in the indigenous working class to the point where some of them routinely support far-right extremist groups.

Yet Blair kept getting elected, despite the misrepresentation of his party and its policies as something approaching centrist or even conservative, for one very good reason: he had a dismal opposition. So craven was the Conservative party in the 2001 election that it was afraid even to raise the question of the National Health Service, the epitome of the bloated welfare state, despite the fact that Blair was being heckled all over the country about Labour’s stewardship of it. In 2005 the Tories deselected one of their candidates, a sitting MP, for suggesting that taxes and spending might be cut. Such idiocies were an invitation to vote for the smooth-talking and utterly plausible Blair, or, more to the point, not to vote at all.

Rudd does a passable imitation of Blair’s smoothness and reasonableness, but lacks Blair’s advantage of a useless opposition. It was clear from the first leaders’ debate last Sunday that Tony Abbott not only has policies, but that they are sensible ones at a time when Australia, buffeted by a world financial crisis and taken backwards by six years of inept, business-unfriendly Labor government, needs to retrench and put itself on a new footing of fiscal rectitude.

Like Blair, Rudd is pretty poor at admitting to unpopular things. Unlike Blair, however, he has an opponent who will give leadership on matters such as reining in public spending, and will appeal to the good sense of the Australian public to applaud his honesty and realism. Whenever Blair felt forced by his party to pursue a policy that many in the country would find unpopular, he had the knack of sloughing off responsibility on to someone, or something else. When the UK parliament wasted an enormous amount of time in 2003 abolishing fox-hunting — a cause dear to the heart of the exceptionally urban Mrs Blair — Blair simply observed that it was the decision of the legislature. When Rudd said that the much-needed expansion of airport capacity in Sydney would be a matter for his deputy and for other colleagues, it was an abdication of responsibility even more outrageous than anything Blair was capable of.

Rudd knows that he must appear more centrist than he really is if people are going to consider entrusting him with another three years of power. Hence his toning down of his rhetoric about climate change policies, and his specious language about a strong Australian economy. He has not, however, brought himself to admit that much public money is being wasted, any more than Blair could when he was in power. But then Rudd, like Blair, sees running a left-of-centre government as a mission to create a client state, whose votes will return his party to power again and again.

Blair, too, abdicated big policy decisions. The biggest of them was of economic policy to his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, whose recklessness and doctrinaire socialism ensured that Britain had a far worse financial crisis in 2008 than was remotely necessary. From the way Rudd disported himself on Sunday, I’d say he’d learned quite a lot from that. I especially admired the way that he seemed to justify higher public spending to help hard-pressed families out of economic difficulty (and, no doubt, towards a Labor vote at the election) without mentioning that it was Labor policies that have largely brought about such problems. And his shambolic handling of the question on immigration policy seemed to an outsider final proof of why Australians could not entrust such a man with three more years of power. Abbott’s point about not handing over immigration policy partly to people smugglers was the right one, and exhibited a clarity of which Rudd would appear to be terrified. But, in Blairite manner, Rudd was careful to allow style to dominate substance, and to con an electorate unattracted by left-wing radicalism into believing they would be getting ‘a regular guy’ — a phrase Blair once used about himself — if they put him back into power. Rudd’s regularity includes breaking the rules of the leaders’ debate by speaking from notes.

It was often said of Blair when he was in power in Britain than he appeared shifty, and that the ministrations of his spin doctors were used to conceal a socialist heart within a body of apparently reasonable policies. That’s Rudd down to a tee. And Australia lacks the excuse of a mediocre opposition that might cause him to have another term of office. Blair’s ten years are what a country gets when its opposition implodes. Luckily for Australia, that problem doesn’t arise.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Simon Heffer is political columnist of the Daily Mail.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in