One of the big differences between Frank Lloyd Wright and me is that, when he was nine, his mother gave him a set of wooden building bricks. When I was the same age, I wanted Lego for Christmas, but my own mother thought it a mere toy, a puerile gift. So she put away childish things and I was given something more high-minded. Perhaps a boring encyclopaedia or a hated chemistry set, useful only for making obnoxious smells.

It was 1876 when Anna Wright presented her boy Frank with Froebelgaben, or ‘Froebel Gifts’, an educational tool devised by ur-pedagogue Friedrich Froebel, who also gifted us the Kindergarten idea: the belief that children’s intellects can be cultivated like flowers. The ‘Gifts’ (which Wright referred to throughout his long and productive life) were coloured woollen balls on string and unpainted wooden cubes, cylinders and spheres. Additionally, Mrs Wright gave him samples of high-quality German art paper.

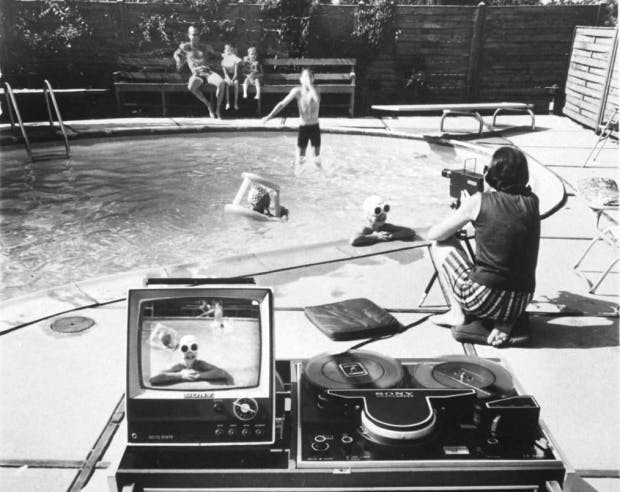

These proved to be one of the most artistically influential gifts of all time (surely even greater than this year’s popular ‘techie treats for tots’, which include a flying fairy that eats expensive AA batteries that are hard to recycle). Sitting at the kitchen table, the future architect became engrossed in form, line and space.

He wrote in his autobiography: ‘I soon became susceptible to constructive pattern evolving in everything I saw. I learned to see…I wanted to design.’ Even as a child, Wright did not want to draw Nature. He wanted to be Nature. Of course, he became one of the greatest architects ever. Meanwhile, the Froebel building bricks continued their adventure in architecture when they became the inspiration for the famous Bauhaus logo.

Lego has educational roots too. In 1949, a Dane called Ole Kirk Christiansen stopped making wooden toys and moved into plastic. His idea was to create a system of interlocking units — he called them ‘Automatic Binding Bricks’ — which allowed children to explore constructive ideas.

Education should teach refinement, encourage discrimination and taste while stimulating individual creativity. This was Lego. Of course it was high-minded (at least compared with the intellectually limited and fast-selling Furby): Lego is a contraction of ‘leg godt’, which means ‘play well’ in Christiansen’s native language.

Today’s Lego bricks, unchanged since a redesign in 1958, are manufactured to a tolerance of one millionth of a metre. They bind together in infinite variety and with beautiful precision, yet disassemble easily. If in their precision, clarity, logic and bright colours we can see something of the achievement of Danish Design as a whole — Verner Panton’s furniture, for example — then that’s an added benefit for connoisseur’s of miniature perfection.

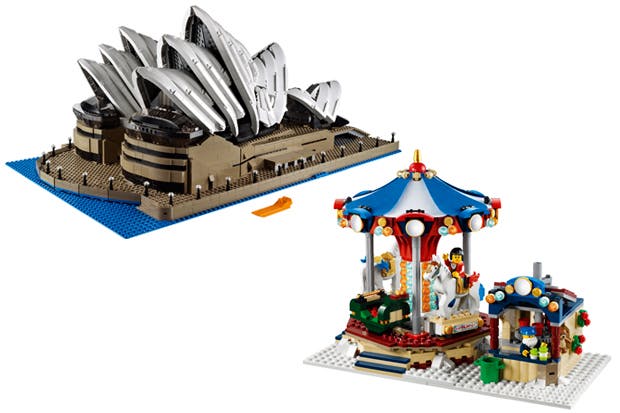

Fortified by seasonal goodwill, I went into Hamleys toy store on London’s Regent Street to check on the current state-of-the-art in building bricks. With a nice symmetry, Lego now sells boxed sets that allow an architecturally inclined child to build little models of Wright’s Robie House in Chicago and his Guggenheim Museum in New York (the latter’s cylindrical form presenting special challenges for rectilinear bricks, just as the real building presented contractors with genius-challenging tribulations of their own). You can also get the Rockefeller Center, the Brandenburg Gate, Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House in Illinois, Tower Bridge and the Sydney Opera House.

Sure, to prescribe what might be built with Lego is, essentially, a denial of the system’s open-ended creative intentions, but only an unseasonal churl would deny that introducing masterpiece architecture to children is an advance, culturally, on selling Christmas super-soakers. Besides, Hamleys Lego emphasises its architectural credentials with a full-size model of Giles Gilbert Scott’s K2 Telephone Box.

But with the idea of the young and inspired Frank Lloyd Wright in mind, Hamleys is a bit of a disappointment, artistically speaking. It is huge, but claustrophobic: an inferno of garish and saccharine tat. The children I saw there looked glum. You must visit to refresh any slumbering sense of outrage at what has been wrought by telly tie-ins mated to high incomes and low brows.

But to be generous, almost everything is available here…except, that is, beauty, charm, sources of contemplation or any suggestion that a child might explore ideas of his own rather than be drowned in the kitsch of media-mandated role-playing fantasies. Easy excess is depressing, especially when you think of a nine-year-old Unitarian pastor’s son playing with shapes and setting a pattern of thought that led to building designs of shocking originality and enduring beauty.

If you understand the constructive and delightful nature of simple play, you understand everything. Froebel knew that. Wright inferred it. Lego knows it. The architect said of his building bricks: ‘These primary forms and figures were the secret of all effects…which were ever got into the architecture of the world.’ Yes, the child is father to the man. And today’s techie treats for tots have all the inspirational value of a dead battery.

The post Building a future appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in