Which disease are you most scared of catching: Ebola or influenza? Before I read this medical memoir, I would have said Ebola. Now, I’d say flu. As Dr Ali S. Khan points out, Ebola is fairly hard to catch; flu is fairly easy. And unlike wimpy man flu, proper flu can be a killer. You’ve heard of the Spanish flu, which killed 675,000 Americans a century ago. But did you know that influenza still kills up to 50,000 Americans every year?

Most pandemics are more like flu than Ebola: they don’t sound that spooky until they get out of hand. Yet instead, we worry about killer bugs which we stand much less chance of catching. When I was a teenager, I was terrified of contracting HIV, though the risk I faced was minuscule. I didn’t worry about meningitis, even though it had already killed one of my best friends. Thirty years later, meningitis nearly killed my teenage son. Belatedly, I learned there are hundreds of different strains of meningitis, and that the vaccines we’re all given only guard against a few dozen. My son’s strain wasn’t one of them. Now which are you more frightened of: meningitis or Aids?

Khan is an American epidemiologist. Until recently he was director of the Office of Public Health Preparedness & Response at the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC for short). The CDC’s job is to stamp out pandemics before they get a proper foothold. This chatty, cheerful book reveals how he went about his work.

According to Khan, being an epidemiologist is a bit like being a private detective. He sifts through lots of paperwork; he treks from door to door. His first case was an outbreak of diarrhoea on a cruise ship. The crew were mystified: they’d cleaned the ship from top to bottom, yet loads of passengers still had the squits. Kahn kept asking questions, however, and eventually he found the answer. The passengers with the runs all drank iced drinks. Bingo! The bug was in the ice.

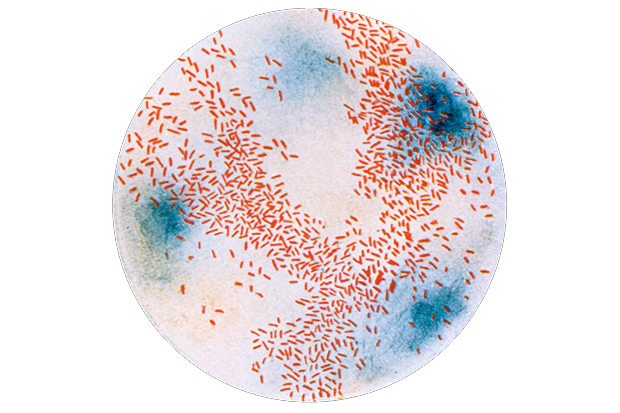

‘We humans act like we own the planet, when really it’s the microbes and the insects that run things,’ says Khan. ‘One way they remind us who’s in charge is by transmitting disease.’ These diseases have taken him all around the world, from anthrax attacks in the USA to monkeypox in the Congo. ‘Outbreak investigations are like solving jigsaw puzzles — or maybe ten of them mixed together,’ he explains. ‘Some of the pieces fit in multiple places. Some pieces are missing. The puzzle you need to solve may be an image you’ve never seen before.’

By rights, this should be a boring book — an endless succession of case studies. That it’s so readable is largely due to the hidden hand of William Patrick, novelist, ghostwriter and book doctor. He has written thrillers about germ warfare and collaborated on books by people ranging from the rocket scientist Adam Steltzner to Aerosmith drummer Joey Kramer (and if you can get an entire book out of a drummer you must be bloody good).

In his preface, Khan thanks Patrick for taking his ‘stream-of-consciousness transcripts from 25 years of public health case-files’ and transforming them into ‘a scientific adventure story’. So does he succeed? Pretty much. Their joint effort is mercifully free from ‘the deathless prose of a journal article’ (as Khan puts it) and amid the crises and tragedies, there are moments of pure comedy. Khan is a Muslim; but eating halal in the Congolese jungle proves to be an uphill struggle. Anxious not to break his dietary laws, he asks local villagers to bring him a goat, which he slaughters himself in the Islamic fashion. Suitably impressed, the villagers bring him a prize pig.

The title is a shameless tease: this isn’t a book about the next pandemic but about various previous ones. It does, however, give you a clear idea of how plagues get started and how best to stop them. Khan’s approach is supremely practical: find the source and then isolate and suppress it. There is no miracle cure.

As he says, the biggest challenge isn’t the science, it’s the social science. Investigating a viral infection in the UAE, he found that the problem came from local sheep, which carried the virus. He advised switching to imported sheep, but no one wanted to. Foreign sheep, he was told, had the face of the devil. Yet, as Khan observes, such ‘magical thinking’ is also prevalent in the USA, where parents refuse to get their children vaccinated against measles because they believe the celebrities who spout the superstition that the vaccines may cause autism. These are the witch doctors of the western world. Why do we believe them?

So should you be worried? Probably. Three quarters of emerging infectious diseases are transmitted from animals to humans. Globalisation is spreading infection around the world like never before. ‘The rest, such as drug-resistant microbes, are completely of our own making,’ says Khan (20,000 Americans are killed by antibiotic-resistant bacteria every year). The microbes that caused my son’s meningitis weren’t drug-resistant. My grandson may not be so lucky. ‘The infamous influenza pandemic of 1918 sickened 20 to 40 per cent of the global population and caused anywhere from 50 to 200 million deaths,’ concludes this modest hero. ‘Sad to say, there is nothing to prevent a pandemic on that scale, and that deadly, from happening again.’

The post Of microbes and men appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in