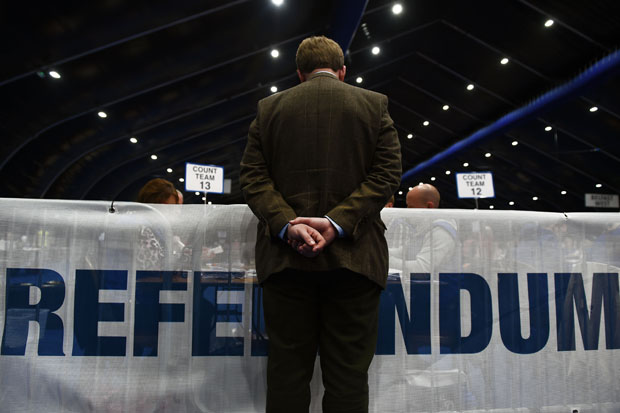

A few hours after voting started in the European Union referendum, Populus released its final opinion poll showing a ten-point lead for Remain. This carried weight because the founder of Populus, Andrew Cooper, was also pollster for the official Remain campaign. His findings had been passed to 10 Downing Street earlier, leading David Cameron and his team to become very confident. There were reports that the Prime Minister was not even going to stay up for the result: he intended to go to sleep early and wake up to victory.

The vote for Brexit, by 52 per cent to 48 per cent, confounded the financial markets and wrongfooted most opinion pollsters. But no one called it more wrong than the chap at the helm of the Remain campaign. Lord Cooper has form: last year, his bullishly named ‘Populus predictor’ gave a wonderfully precise figure for the Tories’ chance of winning a majority: 0.5 per cent. On polling day, he denounced Cameron’s triumphant general election campaign as a ‘prolonged exhibition of insanity’. All of which raises a question: why put him in charge of an EU referendum campaign whose failure could (and did) destroy the Prime Minister?

Those who worked on the Remain campaign found themselves asking this question in the final weeks before the vote. On polling day, for example, they were dumbfounded to find out that Cooper had released an estimate of a ten-point victory. What possible purpose could this serve, other than to set an unhelpfully high bar for the Prime Minister? Or to persuade Remain voters that they didn’t need to go to the polling station on a rainy Thursday, because the race had already been won?

Lord Cooper’s job was to gauge public opinion, the better to direct the efforts of his campaign team. But to the bewilderment of some of his colleagues, he acquired the habit of issuing two sets of polling figures each day. Some staff say he offered no guidance as to which set he believed to be correct. (Cooper disputes this.) One foot soldier in the campaign said: ‘He was sending out polls with a note saying even he didn’t believe the numbers. It’s not great to have your pollster tell you that. To send out two polling figures isn’t just unusual, it’s unprecedented.’

There were also concerns about his other unorthodox behaviour: late-night eruptions on Twitter, and firing off long emails to the Prime Minister without copying in other members of his team. When I asked Cooper about this, he said his second set of (adjusted) polling figures were seen by only a small number of colleagues who knew how to handle the disparity. And that he would always copy at least one of his Remain team colleagues on his emails to Mr Cameron. But not too many of them, because then a personal email would take on the form of an official memo.

Therein lies the problem. Cooper and Cameron have known each other for years, and are very comfortable with each other. Both were Tory party advisers under the Major government when Cooper started to work on what became known as the modernisation project: moulding policies and updating the party image to seem more in tune with modern Britain. It was a great branding success, albeit one that did not translate quite so strongly into electoral success.

The modernisers’ work was largely complete when Cameron was elected in 2010, but the project (and the alliances) survived. The Prime Minister has a weakness for hiring his friends and assembling what his colleagues refer to a ‘chumocracy’. When Cooper was appointed as Cameron’s chief strategist, his critics feared that he was a Tory moderniser first, and a pollster second. That he tended to interpret polling data in a way that reinforced his general political view. And worse, that the ‘modernising’ agenda was at least ten years out of date, making the party unable to judge a changing country.

Two meteors have hit the political landscape in recent years: the financial crash and the global wave of migration. The crash affected everyone, but some recovered more quickly than others. Rock-bottom interest rates sent asset prices soaring, doubling the wealth of those who already had it. For the well–educated and wealthy, globalisation brings new opportunities and dangles the prospect of a jet-set lifestyle. But for the working class and the jobless, it has seemed to bring immigration — which meant competition for jobs, houses and school places. And for some, stagnant wages.

Perhaps the worst blind spot of the Tory modernisers was their disregard for those unsure about globalisation and immigration — who could be disparaged as Old Tories, bigots, or those who could not make peace with the modern world. The losers. If they didn’t like the way the world was changing, well, they could go hang: no one was bringing the 1980s back in a hurry. Modern Conservatives should have no interest in such people.

But as it turns out, such people are now the next big thing. It was the skilled working class that swung the EU referendum campaign. As Brendan O’Neill argues on page 28, they felt they had not been listened to — and, anyway, saw the European Union as an undemocratic scam, emblematic of a new economic order that was making things worse for them and their families.

This is the awesome new opportunity for Conservatives. Labour is in crisis because a third of its voters went for Brexit and might now be ready to abandon the party altogether. If Ukip was semi-functional, then it would evolve into a new party of the working class and do to Labour in England what the SNP did to Scottish Labour. But as things stand, these voters — who were persuaded by Boris Johnson and Michael Gove over Brexit — might well sign up to a reoriented Conservative party.

Just before losing the 1979 general election, Jim Callaghan observed that there are times ‘when there is a sea change in politics. It then does not matter what you say or what you do. I suspect there is now such a sea change. And it is for Mrs Thatcher.’ A similar change is under way now.

The post The pollster who called it wrong. Again appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in