Jeremy Corbyn may not be right about many things, but when he sat on the floor of a train, hoping to raise awareness about overcrowding, he was at least on to something. Of course, in classic Corbyn style, he proved to have ignored reality to make his point: there were plenty of seats on that particular train. It was nonetheless a point worth making. Millions of passengers jostle for standing space every day; Britain’s rail system is in urgent need of help. And there is apparently money to be spent. It just won’t be going on the most overcrowded lines.

Instead, the cash is destined for High Speed 2 — one of those mysterious vanity projects that refuses to go away even though common sense begs it to. Polls show the vast majority of us are against it. I have yet to meet a single person who minds one bit that the travel time between London and Birmingham is 82 minutes rather than 55, as it would be with a new line. The original estimated cost was £30 billion. It has since risen to an astonishing £56 billion, far more expensive than any other high-speed rail line in the world, ever.

But the more the cost rises, the more prime ministers and their secretaries of state for transport seem to love it. It’s a cross-party darling: everyone’s favourite ego-trip. First the New Labour transport minister Andrew Adonis pushed the idea, captivated by the notion of European-style high-speed rail; then George Osborne coveted it after taking a trip on a super-fast maglev train in Japan in 2006 and feeling embarrassed that Britain was being left behind. Philip Hammond supported HS2, allocating £1 billion to be spent on preparations for it; Justine Greening and Patrick McLoughlin nurtured it; and now Chris Grayling has said he has ‘no plans to back away from the HS2 project’. But what about Theresa May?

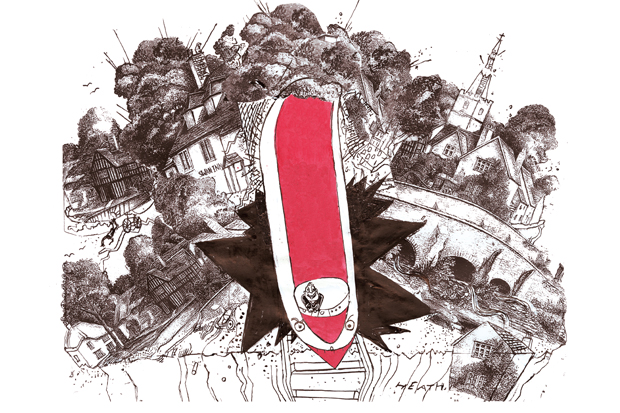

‘Phallic’ is a term you hear used to describe HS2: and when you look at the map, the proposed line, so beloved of powerful men, does seem to go upwards at a phallic angle, with a slight bend at the bottom, between Euston and Old Oak Common. It then proceeds in a virile north-westerly straight line all the way to the Birmingham interchange, where it spurts into a Y shape for the second phase. But now we have a female Prime Minister. Will she put a stop to this macho nonsense?

People living under the blight of HS2 have been holding out hope all summer that she might. Entire communities are waiting to find out if they will be wrecked to make way for the track. In the village of Wendover, Buckinghamshire, houses have been earmarked for demolition. The last season of cricket is being played on the village pitch: if HS2 is granted royal assent in December, it will be a mudheap by next summer.

There’s good reason to think May might be having second thoughts about this absurd project. She has already been bold in her about-turns. Guided by a common-sense approach to economics, she is known to disapprove of plans that aren’t tidy and meticulous. She applied the brakes to Hinkley Point C on the day before the contracts were due to be signed. If she can do that to a nuclear power station, why not a railway line?

Yet during a recent hustings, HS2 was about the only thing Theresa May spoke of with any passion. So while the villagers of Wendover — and the nation as a whole — might wish she would put an end to this much-loathed white elephant, it’s highly likely to go ahead. Prepare for years of chaos, and for the loss of 63 areas of ancient woodland. Prepare for the last few patches of green oasis near Euston to be bulldozed. And be very annoyed when messages from HS2 ask you to ‘consider the environment before printing this email’.

Of course, we need to be hard-hearted as well as hard-hatted when it comes to projects in the national interest. What are a few hundred demolished homes compared to that? But it has become more and more clear that HS2 is not in the national interest, and that, far from helping to create a ‘northern powerhouse’ — an Osbornian phrase May seems reluctant to utter — it will suck hundreds of thousands of people southwards towards London. The ‘new city’ to be built between Birmingham and Coventry will be a dormitory town for the London commuter. Even Lord O’Neill, the former Goldman Sachs economist who was hired as a commercial secretary to the Treasury by George Osborne, sees this truth clearly. He now believes it would give far more power to the north if the government made its priority HS3, a project that would connect Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds and Hull. This interconnection of northern cities really could produce a northern powerhouse to rival the southern one.

Chris Grayling now claims that HS2 is ‘a capacity project’ rather than one to promote speed. And it’s true that the number of rail-users is rising each year. But if you look at statistics about overcrowding on trains, the Euston-to-Birmingham line never gets a mention. It’s only at 60 to 70 per cent capacity. Meanwhile, all over Britain on small, unglamorous railway lines, the degradations and humiliations of the daily commute continue.

Southern Rail, with its summer of strikes, reduced services and closed stations, is just one example. Crowding on to packed trains, nose to armpit, commuters start their working day in helpless, exhausted misery. They don’t even bother to look for a seat: no chance. They can’t use the travel time usefully because they have to hang on tight — all they can move is a thumb to play a game on their smartphone. Imagine if some of the £56 billion to be spent on HS2 could instead be used to make small improvements to hundreds of different lines, lengthening platforms and trains, re-opening closed stations, and installing reliable onboard Wi-Fi. It might not be a high-profile project but it would relieve the national stress level far more effectively than it would helping a few business travellers on expenses shave 25 minutes off their journey.

As HS1 in Kent showed, lavish high-speed train projects are intended for the well-off, because these are the only people who can regularly afford to travel on them. Normal mortals chug along on slower, cheaper trains. Railways are far from an egalitarian form of travel, and HS2 would make them even less egalitarian than they already are.

We’re a train-loving nation, and so we should be. We fall in love with our country when we see it from a train, much more than we do from a car. The raspberry bushes in the deep backs of long gardens, the delicious leafiness of it all, the rhythmic sound as the train rattles through a cutting — these are wonderful things, on a human scale. However much modern rail companies try to de-romanticise train travel — by installing horrible lavatories with panic-inducing slow-closing circular doors and press-button locks, and ‘airline’ seats not aligned with the windows — we still cling to the romance of train travel and would far rather be stuck on a slow train than in a traffic jam. Has there ever been an ‘Adlestrop’ of motorway driving? I don’t think so.

The thing about HS2 is that it spits on communities. It doesn’t love this country. It whooshes past it on a concrete viaduct, leaving nothing but noise. Residents of Wend-over, hearing the constant roaring of the train in 2026, will be reminded that it does nothing to help their lives. The nearest station would be 35 miles away, in London. If this line is built, it will be a triumph of globalised marketing-speak over reality. I went to a meeting of residents about to lose their homes or local parks near Euston and saw what they were up against: six HS2 employees in smart clothes, slithering out of any tricky questions or agonised concerns with ‘Can I take that away and think about it?’ and ‘That’s not necessarily something I can come back on quickly.’

Theresa May has spoken about wanting to heal this country in the post-Brexit era. But while the nation may be divided on many issues, on the matter of HS2, it is broadly united. We hate it. I’d love to see the look on the faces of those who commissioned this testosterone-fuelled boondoggle if Theresa May turned round and said of it, ‘Let’s have a rethink, shall we?’

The post The vanity line appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in