Craig Raine

Philip Hancock’s pamphlet of poems Just Help Yourself (Smiths Knoll, £5): charming, authentic, trim reports from the world of work — City and Guilds, pilfering, how to carry a ladder, sex in a van (‘From the dust-sheet, wood slivers/ and flecks of paint stick to her arse’). One poem is called ‘Knowing One’s Place’; these poems know the workplace.

Nutshell by Ian McEwan (Cape, £16.99) was hilarious and compelling. The Pier Falls by Mark Haddon (Cape, £16.99) was grim and compelling. Both books are ripping, gripping yarns — narrative Velcro.

Paul Johnson

John Bew’s biography of Clement Attlee, Citizen Clem (Riverrun, £30), is a winner, though it might have been improved by cutting. Attlee was a more interesting man than people supposed. He read an average of four books a week, wrote a good deal of verse and almost made a movie. He was acerbic. The sharpest letter I received during the six years I edited the New Statesman came from him. My consolation was that he regularly received similar rebukes from his fierce wife, Violet, delivered verbally.

The book I most relished was Edgar Peters Bowron’s Pompeo Batoni: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, two volumes in a boxed set (£195). It fully holds up Yale’s reputation as the world’s best art publisher: scrupulous scholarship, superb illustrations and matchless reproductions. Batoni was the most accomplished of the Grand Tour portraitists and for anyone building up a library of 18th-century culture, this is a must.

Finally a word in favour of Grumbling at Large: Selected Essays of J.B. Priestley, with an introduction by Valerie Grove (Notting Hill Editions, £14.99). The master-craftsman misleadingly known as ‘Jolly Jack’ writes: ‘I have a sagging face, a weighty underlip, a saurian eye and a rumbling voice. Money could not buy a better grumbling outfit.’

Mark Cocker

Two nature books have really stood out this year. The Great Soul of Siberia: In Search of the Elusive Siberian Tiger (Collins, £16.99) is by the Korean filmmaker Sooyong Park, who has been on the trail of his totem animal for 20 years and singlehandedly obtained most of the cinematic footage which humankind possesses of this, the largest felid on earth. He has now produced a classic evoking the utterly bleak landscapes of Siberia as well as the grotesque abuse meted out to wildlife by poachers. Yet the book is most memorable for its soaring beauty and for Park’s Franciscan love for his fellow creatures.

Jennifer Ackerman’s The Genius of Birds (Corsair £14.99) is by a journalist, but her command of the latest findings on avian intelligence matches that of any top-notch researcher. This is science writing at its best: a book of knowledge, packed with mind-stretching information, but also steeped in a sense of wonder and written by someone clearly moved by the vast complexities of life.

Stephen Bayley

I told James Stourton that the world didn’t need to know anything more about Lord Clark of Trivialisation. And I was wrong. His meticulous and elegant book, Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Criticism (Collins, £30) perfectly captures the contradictions of ‘K’, an Olympian snob, but a true democrat who was thrillingly honest and also hard on himself. Britain’s best writer on art since Ruskin now has the biography he deserves.

Before he took his life with his own hand, the Infinite Jest author had used that same hand to play tennis at the US equivalent of county standard. The sport remained an obsession and if tennis is not itself a high art, writing about it this well most certainly is — as David Foster Wallace does in String

Theory (Library of America, £15).

My manic eccentricity award goes to Graham Robb, whose books on French culture have been justly popular. Now, in Cols and Passes of the British Isles (Particular Books, £20), the easygoing Robb has researched and catalogued Britain’s 2,002 cols, many of them hitherto unnoticed (including one in south London): a delicious and hypnotically fascinating

masterpiece of squinty-eyed fanaticism.

Ruth Scurr

‘Memory is a creature that is alive… nobody has simple relations with memory,’ Svetlana Alexievich told the Cambridge literary festival earlier this year. She was speaking through a translator about Second-Hand Time, first published in English in 2016 (Fitzcarraldo Editions, £14.99) and her earlier books including Chernobyl Prayer and War’s Unwomanly Face. Alexievich claims that she does not conduct interviews, only conversations, and that the stories she collects — about the collapse of communism, the suffering of those with radiation poisoning, and the experiences of women during the second world war — involve giving something of herself. Her books are repositories for voices that would otherwise be lost. Lest anyone think Alexievich is concerned only with grim and disturbing topics, her next book is about the experience of love. She is my discovery of 2016.

Hilary Spurling

I choose Ian Collins’s Rose Hilton (Lund Humphries, £35), a remarkable artist elbowed aside, like so many women of her generation, by a more established, much better known and far more forceful husband. Roger Hilton reckoned there was room for only one artist in their household, and that was him. This handsome, inviting and splendidly illustrated volume follows Rose as she makes her own way, with a lot of help from Matisse and not much from Roger, to emerge after his death as an authoritative colourist of great strength and warmth in her own right.

Catrine Clay’s Labyrinths (Collins, £20) tells a parallel story from 50 years earlier, following Emma Jung as she too fought free of Carl’s shadow, to take her own place, after years of struggle and rebuff, in the turbulent world of psychoanalysis.

A.N. Wilson

Michael Denton’s Evolution: Still a Theory in Crisis (Discovery Institute Press, £16.80). A sequel to his 1985 book — Evolution: A Theory in Crisis — this takes us up to date with the dazzling developments of life sciences over the past 30 years. Denton is a sceptic about Darwin’s theory of evolution on purely scientific grounds. It is hard to see how anyone reading his book could not be persuaded. Palaeontology provides abundant evidence of evolution within species, but none of one species morphing into another. Denton is fascinatingly clear in his exposition of the science of genetics, and how it destroys the Darwinian position. A truly great book.

The best new novel of the year, for me, was The Huntingfield Paintress by Pamela Holmes (Urbane Publications, £8.99), about the Victorian wife of a Suffolk parson who paints the parish church in all the poly-chromatic glory it would have known in pre-Reformation times. The story is a true one, but Holmes has written a profound novel about Mildred Holland’s marriage, and her relationship with her times. A double treat, if you read the book, and then go to see Mildred’s stupendous work for yourself. Golden angels sing from the beams and technicolour saints halloo you from the roof of the nave.

Jan Morris

Two of my most memorable books of the year were by two of the most brilliant writers of our day, and were both, to my simple mind, of opaque allure. Colin Thubron’s novel Night of Fire (Faber, £16.99) evokes the emotions of seven tenants, plus their landlord, when their apartment house is burnt down, and fascinatingly jumbles them all into a mystique contemplation of something or other.

Geoff Dyer’s White Sands (Canongate, £16.99) is subtitled ‘Experiences from the Outside World’ and is a virtuoso display of his particular kind of travel writing, sometimes fact, sometimes fiction. I was only half convinced by it all, but quite bowled over by the title story of the collection, which seems to me a little masterpiece.

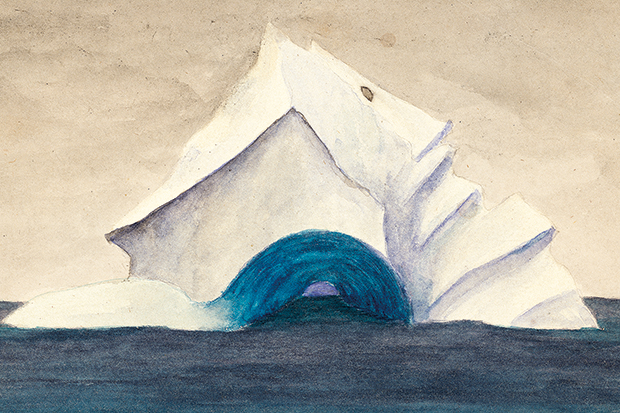

Frank Boas’s sketch of an iceberg made en route to Cumberland Sound. From Thames & Hudson’s Explorers’ Sketchbooks

But for pure unchallenging delight, I most enjoyed an astonishing collection of works of art created by explorers and adventurers down the centuries. It is a beautiful multi-edited sort of album, entitled Explorers’ Sketchbooks and published by Thames & Hudson at £29.95. If it were not such a sumptuous volume it would be glorious for reading in the bath.

Anna Aslanyan

The philosopher Simon Critchley wrote On Bowie (Serpent’s Tail, £6.99) to say, with eloquence and feeling, what many have tried to say over the past year. Upon learning of the death of the icon, Critchley spent the evening of 11 January listening to Blackstar. ‘It simply sounded different, and (although this is obviously absurd) it sounded like Bowie was speaking directly to me.’

The Transmigration of Bodies is the second novel by the Mexican writer Yuri Herrera to appear in English (And Other Stories, £8.99). Herrera’s talent for portraying ‘liminal situations’ puts him in the same league as J.G. Ballard, while his ability to switch between registers and his inventive language, skilfully rendered by the translator Lisa Dillman, make for unique reading.

The Man Booker judges were impressed enough by J.M. Coetzee’s The Schooldays of Jesus (Harvill Secker, £17.99) to longlist it, but it was as disappointing as its prequel.

Richard Ingrams

The death of Jeremy Thorpe aged 85 in 2014 finally made it possible to tell his extraordinary story without fear of the libel laws. John Preston has seized the opportunity in his gripping account A Very English Scandal (Penguin/Viking, £16.99). The leader of a political party involved in a murder plot easily trumps any other political scandal of our times; but the fact that in the event it was only a dog that died gives the story an air of farce.

Apart from Thorpe himself, vain and intensely ambitious, Preston handles with great skill a cast of astonishing characters. These include Thorpe’s devoted ally, Peter Bessell, who later betrayed him; and his monocled, cigar-smoking mother, Ursula; not to mention the two lawyers who got him off the hook — the brilliant barrister George Carman and the grotesquely biased judge Sir Joseph Cantley. All the major players are now dead, apart from the troubled soul who started it all — Norman Scott, who lives on in a Dartmoor village with 70 hens, three horses, a parrot, a canary and five dogs.

Daniel Hahn

I’ve chosen two very different stories of young American lives. In Another Day in the Death of America (Guardian/Faber, £16.99), the journalist Gary Younge anatomises American society and its squandered potential by means of a simple conceit: he chose a random date in 2013 and investigated the lives of those children and teenagers shot and killed on that day. It’s a profoundly important piece of reportage, seemingly written with restraint but devastatingly powerful.

Bonnie-Sue Hitchcock’s debut, The Smell of Other People’s Houses (Faber, £7.99), is a gorgeous young adult novel, interweaving the lives of four teenagers in small-town Alaska in the 1970s — their community, their struggles and joys. Younge and Hitchcock probably have little overlap in their readerships, but their books, besides being two of the best I’ve read this year, are also exceptionally good at taking characters one would expect to be incomprehensibly distant and bringing them close — making us feel an intimate part of their lives and they of ours. They’re both, in short, exemplary reminders of that thing books do best.

Mark Mason

I thought I knew my Macca, but then along came Philip Norman’s Paul McCartney: The Biography (Weidenfeld, £25). We see the star asking for vegetarian food in his Tokyo jail (he is allowed apples and oranges, but not bananas, in case guards slip on the skins) and letting a visitor to his Sussex home handle the famous Hofner bass. ‘Don’t drop that,’ says McCartney. ‘It’s insured for two million.’

Jonathan Mayo’s Titanic: Minute by Minute (Short Books, £8.99) is gripping. It took longer than you’d think for the ending to become clear — nearly half an hour after impact, passengers were happily adding fragments of the iceberg to their cocktails.

Stewart Lee’s Content Provider: Selected Short Prose (Faber, £14.99) is as brilliantly crafted as his stand-up. Could there be a better summation of Louise Mensch than that one of her ideas ‘spurted though the

Twitterverse like a frozen spear of urine falling from an aircraft toilet’?

Daniel Swift

My book of the year was not published but reissued this year. It is The Last Samurai by Helen DeWitt (Vintage, £9.99), and was first published in 2000 but fell into some obscurity, partly due to the release of a truly rotten Tom Cruise movie with the same title in 2003. DeWitt’s novel (not Cruise’s film) is about Greek dictionaries, comparative linguistics, Bach and samurai. A hyper-educated single mother brings up her son by exposing him only to high culture and works of genius. In the second half of the book the son, kitted out like a samurai with only this rarefied equipment, sets out on a quest to find — or perhaps to invent — his absent father. It’s a brilliant and sad book, about being a child, about reading and parenting, about art’s relation to the world. It’s also the funniest book I’ve read in years. Let’s not let it vanish again.

Mark Amory

Anne Tyler’s Vinegar Girl (Hogarth, £16.99), her modern version of The Taming of the Shrew, came as a surprise: the funniest book she has written, much funnier than Shakespeare.

Private Eye considers that I should not praise Ferdinand Mount because I was at Eton with him but we never spoke to each other there, so perhaps it is acceptable to mention his English Voices: Lives, Landscapes and Laments 1985–2015 (Chatto, £15.99): a large volume of his reviews, I think literally without a dull page.

Otherwise, I have been catching up on good books I have never got round to. I was going to say that Paul Scott’s The Raj Quartet was underrated until I came across a review stating that it was Tolstoyan in scope and Proustian in detail, so I’ll settle for a huge, gripping achievement. Among Penelope Fitzgerald’s extraordinary novels, I particularly liked The Beginning of Spring (Harper Perennial, £8.99) and The Bookshop. I thought I did not care for historical novels but it seems I do.

Disappointment: Dickens thought that he was at the height of his powers when he wrote Martin Chuzzlewit. He was wrong.

Clare Mulley

2016 has been a good year for the Nazis. For The Gestapo: The Myth and Reality of Hitler’s Secret Police (Hodder & Stoughton, £9.99), Frank McDonough trawled surviving records to provide new insights into the workings of Hitler’s terror state and the perennial questions around coercion and consent.

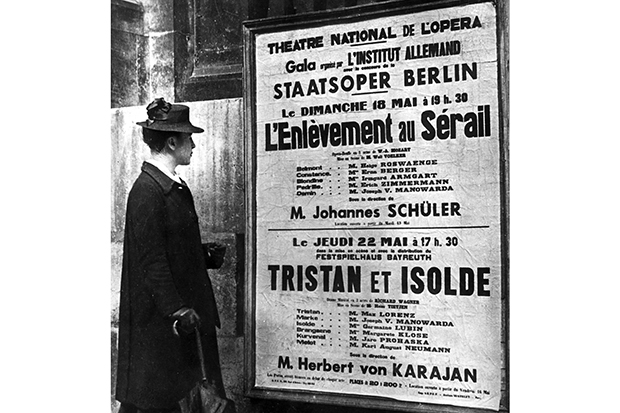

An elegant Parisienne examines what’s on at the Paris opera in 1941

Two books examining responses to the Nazis’ rise and fall have also stood out for me this year. Anne Sebba’s Les Parisiennes: How the Women of Paris Lived, Loved and Died in the 1940s (Weidenfeld, £20) skilfully weaves the history of wartime and postwar Paris through the stories of women from all walks of life. Turning the better-known Paris tapestry over in this way reveals fascinating and sometimes long-hidden threads. It is the responses of artists and writers to the aftermath of Nazi Germany, as Europe began its new transformation, that are examined in Lara Feigel’s engrossing The Bitter Taste of Victory: In the Ruins of the Reich (Bloomsbury, £9.99). All three books address differing human responses to crises and atrocities, and all three resonate today.

Sara Wheeler

Far and Away: How Travel Can Change the World is a collection of pieces by the American essayist Andrew Solomon (Chatto, £25). From Moscow to Mongolia, Antarctica to Afghanistan, Solomon observes the world and reflects what he sees both on himself and on his own country. Resilience, hope, flux: Solomon has an outsider’s eagle eye. A dazzling volume.

I also enjoyed On Reading, Writing and Living with Books (Pushkin Press, £4.99). This slim tome is among the first of a gorgeous new series culling extracts from the shelves of the London Library, an institution which celebrates its 175th birthday this year. Authors anthologised include Virginia Woolf and George Eliot. In half an hour, this book delivers the fruits of many days cruising the stacks in St James’s Square.

Marcus Berkmann

I loved Deborah Levy’s Hot Milk (Hamish Hamilton, £12.99). It’s a short, characteristically oblique story of a young woman in southern Spain with her crapulous mother, there to attend a dodgy-sounding, marble-adorned medical establishment where they hope to find — at last — a cure for the mother’s inability to walk. It’s no surprise it didn’t win the Man Booker prize, because as well as being elegant and deeply strange, it’s hummingly funny throughout. As we all know, prize juries regard jokes as a distinct

disadvantage.

I’m reviewing the year’s cricket books at the moment for next April’s Wisden, and the outstanding volume so far has been The Grade Cricketer, by Dave Edwards, Sam Perry and Ian Higgins (Melbourne Books, £14.99). This is actually even funnier than Hot Milk, a faux-memoir by a low-level Australian cricketer of modest talents, who knows that scoring runs and taking wickets matter less than the possession of a good ‘rig’ (body) and a decent grasp of Anchorman quotes. ‘Most grade cricketers have contemplated switching clubs at one stage or another. As humans, we have an inherent tendency to think the grass is greener on the other side. But all grass looks the same when you’re standing on it for six fucking hours every Saturday, wondering what you’re doing with your life.’

Peter Parker

My novel of the year was What Belongs to You (Picador, £12.99), Garth Greenwell’s slender, poised, clear-eyed and devastating account of the depths to which unrequited sexual obsession can lead you, particularly if you become entangled with a rent-boy in Sofia. I also enjoyed and admired Aravind Adiga’s funny and touching Selection Day (Picador, £16.99), in which cricketing prodigies in Mumbai face googlies from both bowlers and life. And Tom Bullough’s densely and thrillingly written Addlands (Granta, £14.99), which traces the lives of a farming family on the Welsh borders through 70 years. Treat of the year was Richard Stokes’s The Penguin Book of English Song (Penguin, £30), an original and invaluable anthology of poems that have been set to music. Arranged in chronological order by author, from Geoffrey Chaucer to Sidney Keyes, it is supplemented with succinct, elegant and illuminating descriptions of the lives and works of both poets and composers.

Kate Womersley

As events unfolded this year, it was reassuring to read superb non-fiction that celebrated expertise. Two stand out. Trials: On Death Row in Pakistan (Penguin, £16.99) tells how Isabel Buchanan, fresh from a law degree, applied her feeling and intelligence to apprentice in a jurisdiction which, by 2014, saw a person executed every day. Ed Yong’s magnificent revaluation of bacteriology, I Contain Multitudes (Penguin, £20), counsels humility for student doctors like me: modern medicine’s pathogens may be the future’s therapeutics.

And then there is Mark Greif’s Against Everything (Verso, £16.99), which — as its title suggests — matches brilliant critique with improbable optimism. His essays risk embarrassment to analyse the irritations of urban life — hipsters, foodies, gym-goers — so that we might see these characters in ourselves, and treat them with, if not more kindness, more interest.

From the lives of others elsewhere to the trillions of microbes inside us, all three books interrupt our unimaginative monologues, and prompt us to ask better questions.

James Walton

Lionel Shriver’s The Mandibles: A Family, 2029–2047 (Borough, £16.99) is set in a bankrupt America where the middle classes are foraging to survive. All aspects of the dystopia are thoroughly and chillingly imagined — but without ever losing the psychological plausibility of a gripping family saga.

My other favourite novel was Jonathan Unleashed (Bloomsbury, £14.99), Meg Rosoff’s first work for adults. For some writers, twentysomething Jonathan’s inability to ‘cross the huge gulf between childhood and adulthood’ might be evidence of male inadequacy. Rosoff, though, shows how right he is to be scared about growing up, in an exhilarating read that makes abiding pessimism very funny indeed.

Finally, for all music fans, there’s David Hepworth’s 1971 (Bantam, £20), which argues — and very possibly proves — that 1971 was the best ever year for rock albums. Mixing great anecdotes with thoughtful criticism, this is a richly entertaining reminder of when LPs ruled the world.

Honor Clerk

The Vanishing Man (Chatto, £18.99) by Laura Cumming is a moving memorial, written in the wake of the death of the author’s father. An impassioned celebration of Velázquez and a snapshot of the snobberies of the art world in the mid-19th century, it’s a cracking good story to boot.

By contrast, a slow read rather than a page-turner, Ann Wroe’s Six Facets of Light (Cape, £25) is a compendium of art, literature and science that takes you from Fra Angelico and Eric Ravilious, Milton and Gerard Manley Hopkins to Einstein, Newton and Clerk Maxwell. A book for winter.

Graham Robb

My novel-reading year has been dominated by Barbara Pym, starting with Excellent Women (Virago, £8.99). Pym is usually likened to Jane Austen, but her hilarious situation comedies and recurring characters constantly reminded me of Balzac.

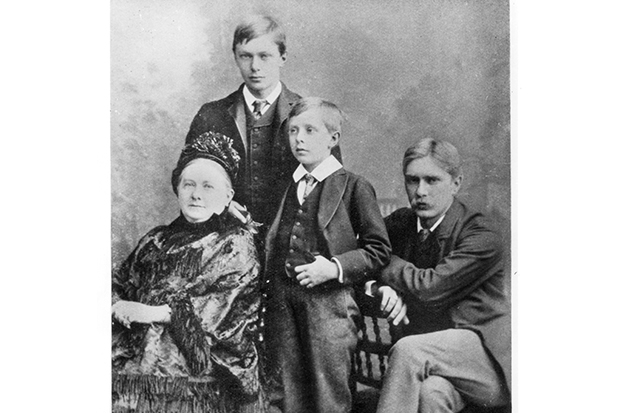

‘Chalk Paths’, by Eric Ravilious

Island Home: A Landscape Memoir (Picador, £12.99) is an all-too-brief autobiography by the novelist Tim Winton. He sees Europe with the eyes of an extra-terrestrial, finding nature ‘impossibly fertile’ and the Alps ‘claustrophobic’. As an unhappy schoolboy in Western Australia, he explored the violent, delicate landscapes which cars have erased, rendering ‘the outlandish mundane’. Winton’s dry, physical descriptions have the opposite effect.

Hannah Kohler’s The Outside Lands (Picador, £12.99), the tense saga of an American family at the time of Vietnam war, struck me as the work of a seasoned American novelist though, apparently, she grew up on the south coast of England and this is her first novel.

David Crane

Lyndal Roper’s Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet (Bodley Head, £30) is an impressive and fascinating read. I have no idea what Lutherans have made of it, but for those of us who have harboured an irrational dislike of this extraordinary and unpleasant man, it’s a comfort to know we weren’t completely wrong.

It’s taken me a long time to come across her, but it’s hard to imagine there is a better short-story writer than Deborah Eisenberg. All unmistakably hers, all intriguingly different, and almost all brilliant, her Collected Stories (Picador USA, £17.75) brings together 30 years’ work that shows no sign of going off in quality.

John Sutherland

Best novel: no question, Razor Girl by Carl Hiaasen (Atlantic Books, £13.50). A Florida comcrime (I just made that word up) which makes you feel better about the US in a year when that’s been tricky. You can be sexually saucy and inoffensive — a lesson Donald has never learned.

It’s been a crowning year for our best living literary critic, Sir Christopher Ricks. His long campaign for Bob Dylan to be taken seriously in a literary way has triumphed. His edition of The Poems of T.S. Eliot, with his co-editor Jim McCue, (Faber, two volumes, £26 each) is (literally) monumental and will last for as long as poetry is read.

Peter Parker’s Housman Country: Into the Heart of England (Little Brown, £19.99). Parker — one of the few biographers, I suspect, who has actually shorn a lamb — penetrates to the Englishness at the heart of A.E. Housman. The book is appropriate for a year which may see the end, or rebirth, of the country.

The most poignant memoir of 2016 was Beyond the High Blue Air (Atlantic Books, £14.99), Lu Spinney’s account of her son’s vegetative condition after a snowboarding accident and the cruellest decisions a mother can be confronted with. Exquisitely written.

Philip Marsden

More of Patrick Leigh Fermor this year, with a selection of his letters, Dashing for the Post, edited by Adam Sisman (John Murray, £30), in which he gushes and charms and enlarges the world with his enthusiasm for its people and its pasts.

As a traveller Geoff Dyer is a little more sardonic. The faraway places in his White Sands (Canongate, £16.99) are filled with disappointment, with the press and pallor of the present. But he writes with such wit and brio that you can’t help wanting to be there with him.

The post Books of the year appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in