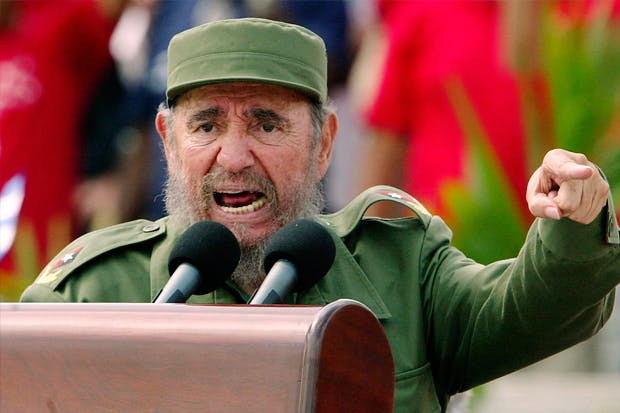

Whatever else may be said of the late Fidel Castro, he has one distinction no-one can take from him or is likely to equal in the future: he was the only man in history who actively sought to provoke a nuclear war between the super-powers.

He had asked the Soviet Union to install nuclear missiles in Cuba in 1962 and was furious when Khruschev withdrew them in response to President Kennedy’s blockade instead of launching them (Perhaps he was looking forward to haranguing an audience of obedient cinders). He may more recently have played a part in swinging an important part of the Hispanic vote in the US – the Cuban exiles and refugees in Florida – to the Republican Presidential candidate.

Those émigrés – filmed dancing in the streets at news of his death – had not forgotten or forgiven President Obama’s cosying up to him – an action undertaken despite the pleas of the heroic Cuban dissident democratic leaders and one which represented a heavy blow to any hopes of installing a democratic regime there. It was not the least of Obama’s impressive, indeed virtually unblemished, record of foreign policy disasters.

One leading dissident who went on a hunger strike over the state of human rights, which he claimed had actually got worse since Obama’s one-sided détente with Castro, was tricked into quitting by what looked like a KGB-style ‘active measures’ operation; a fake website falsely claiming his demands had been met.

Upon coming to power in 1959, Castro’s government at once built a highly effective machinery of totalitarian repression. By September 1959, KGB agents were in Cuba advising the security service. Jorge Luis Vasquez, a Cuban imprisoned in East Germany, states that the East German secret police also trained the personnel of the Cuban Interior Ministry. The death penalty, which had been at least formally abolished by the previous regime (an abolition probably honoured in the breach rather than the observance) was formally re-instated, and the usual Communist jurisprudence held sway. There were hundreds of executions. Other dissidents were held in tiny cells until their leg-muscles atrophied, confining them to wheel-chairs. Amnesty International reported in December last year: ‘Cuban human rights activists are at increased risk of detention or harassment from the authorities amid demonstrations on International Human Rights Day, 10 December.’ There had then been almost 1,500 arbitrary arrests in just over a month. ‘Police in Havana arbitrarily restricted the movement of members of the prominent Ladies in White (Damas de Blanco) group of activists as they prepared for today’s demonstrations.’ This came after at least 1,477 politically motivated detentions in November 2015, according to the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation.‘For years, harassment on Human Rights Day has been the rule rather than the exception.’

Human Rights Watch says Cuban prisons are overcrowded, inmates are forced to work 12 hours a day and punished if they fail to meet production quotas. Outside monitor organisations are not allowed to visit the prisons. Further, ‘arbitrary arrests of human rights defenders, independent journalists, and others have increased dramatically in recent years. Other repressive tactics employed by the government include beatings, public acts of shaming, and the termination of employment.’

Castro and his associates, as soon as they gained power began confiscating, well, everything, and without compensation. It was this that led Ernest Hemingway to praise Castro and pose in a propaganda photograph fishing with him – it was not that he approved of the confiscations, but that he was trying to escape them and to keep his own property in Cuba. One of the dictator’s Marxist supporters admiringly stated that Castro even took his widowed mother’s lands. Despite resisting, she was ‘allowed’ to stay under protection thanks to the ‘benevolence’ of little brother and successor-dictator Raúl.

The general level of happiness and prosperity Fidel brought his people can be judged by the number who crossed, or drowned in attempting to cross, 90 miles of open ocean to Florida on old inner tubes. Like other communist leaders who brought their countries dictatorship and poverty, Castro basked in the admiration of prominent Western intellectuals, artists and progressive clergymen. Ideology-addled American students tried to get to Cuba to help bring in the sugar crop. Why this sort of thing happens with even the most repulsive dictators remains a mystery, though Professor Paul Hollander has done important work documenting this form of pathology in Political Pilgrims.

Vladimir Putin called Castro ‘a sincere and reliable friend of Russia’ who had built ‘an inspiring example for many countries and nations’. From Putin this might be expected. President Obama made a statement, described as ‘pathetic’ which avoided saying anything. Turnbull has said nothing at all. Castro groupies like Canadian PM Justin Trudeau and the increasingly ludicrous former US President Jimmy Carter showed themselves in their true colours with eulogistic obituaries for the ghastly dictator.

One of his more starry-eyed groupies in later years was the ineffable Pope Francis, who, possibly forgetting his earlier support for the quasi-fascist junta in Argentina, referred to his death as ‘sad news’ and told Raúl, ‘I express to you my sentiments of grief’ – sentiments which had not been on show during the regime’s often lethal persecution of the Catholic Church. The two previous Popes had met Castro but had at least confronted him on his behaviour. Francis broke from the Vatican’s usual practice of having the Secretary of State send official condolences. In a mark of the great personal esteem the Pope held for Castro, Francis signed the telegram himself.

Last year, Francis visited Castro for what were described as ‘intimate and familial’ discussions, with Cuba’s human rights record presumably not high on the intimate and familial agenda. During that visit, democracy activist Ángel Moya, who had previously been imprisoned for eight years, and his wife Berta Soler – the leader of the dissident group Ladies in White – had been among several dozen people detained by Cuban security officials to prevent them attending the Papal Mass. Others were arrested when they tried to approach the Pope. A disgusted Moya was moved to say then: ‘We’ll defend our rights with or without the pope. He is no liberator.’

One can only hope that when the elderly Raúl Castro also finally dies, the virulence of the regime may begin to modify.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in