With the onset of the so-called festive season, I fear that two of the more significant newspaper articles of recent times could easily have passed us by virtually unnoticed. Both appeared in the Australian.

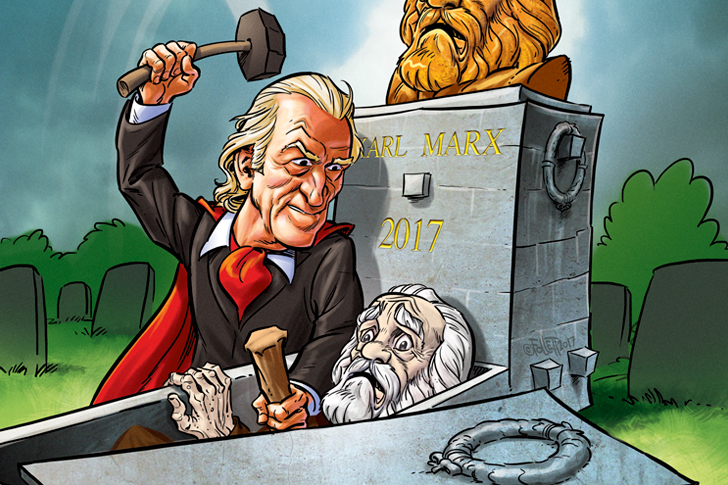

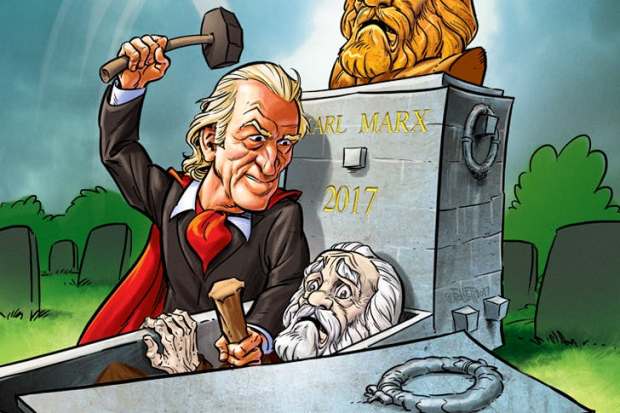

What I suggest, at the start of a new year, is that placed together this pair of articles has great significance for the future of Australian life since both now implore us, for the good of all, to cease our overlong and largely delusory national obsession with Marxism and its ‘neo’ derivatives. Indeed, no more appropriate moment could possibly exist for such a cessation than the year of the centenary of the Bolshevik revolution.

The first article by Kevin Donnelly, a senior research fellow at the Australian Catholic University, appeared on December 28. Its sub-heading which reads ‘Let’s drop Marxist-inspired nonsense and get our children back to basics’ is more or less self-explanatory – at least to the culturally sane. In Australia Kevin Donnelly is known, among other matters, for his sterling work on a national curriculum – a role to which I contributed myself on a British version more than a quarter of a century ago.

The headline of the second article on January 3 – which was a reprint from the Times in Britain – is certainly no less explicit: MARXISM BELONGS IN HISTORY’S BIN AFTER 100 YEARS OF HELLISH FAILURE and the start of the article, by Matt Ridley, could hardly state its intentions more clearly: ‘Human beings can be remarkably dense. The practice of bloodletting, as a medical treatment, persisted despite centuries of abundant evidence that it did more harm than good. The practice of communism, or political bloodletting as it should perhaps be known, whose centenary in the Bolshevik Revolution is reached this year, likewise needs no more tests. It does more harm than good every time. Nationalised, planned one-party rule benefits nobody, let alone the poor.’

Ridley took us by the hand and led us through a century full of communist horror stories which collectively killed an average of a million people a year. But what is a little matter of a 100 million deaths among friends – or should I say comrades – providing, of course, that they died as a result of a familiar, brutal and unworkable ideology?

Half a century ago I met a Russian-born musician, Galina Solodchin, who was the first person to alert me to the terrible plight of citizens then in Soviet Russia. She had escaped with her grandmother on foot via Russia and China before making her way to Australia – where she won an international violin contest – and finally arriving in London.

The horrors of what occurred in the Soviet Union aside, we can now look back on the frequently murderous history of China since 1949, followed by locations such as Cuba, Burma, Benin, Zimbabwe – where Robert Mugabe put into practice much of what he had learned at the London School of Economics – the Congo, and rather nearer to home, Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge managed to kill roughly a third of that unfortunate country’s entire population. Finally, in Ridley’s own words: ‘North Korea managed to turn communism into a feudal dynasty of unparalleled paranoia, which not only executes supposed dissidents in unusually gruesome ways but managed to starve millions of its own citizens during the 1990s, a time when the rest of the world was feeding itself ever more abundantly’.

The alternative to international Marxism is not laissez-faire economics based roughly on a model provided by Goldman Sachs and other so-called ‘merchant’ banks but a novel form of capitalism which performs – and is made to do so by law – under a far-reaching ethical umbrella.

In short, money – and the ruthless and unprincipled pursuit of it – should never be regarded as the sole or even a major purpose of sensible human existence. Instead, national pride needs to be based once more on self-reliance and communal courtesy and concern. Britain, in the years following the Second World War, was, for example, much more unified in its sense of public concern than it is today, and it is my guess that Australia was once similarly a more cohesive, principled and self-confident nation. Prior to the mid-Sixties – or early Seventies in the case of Australia – secularised Christianity formed the moral basis for the greater part of civil, intellectual, legal and academic life – as in most other free Western democracies. Yet none of the latter countries basically valued themselves enough to withstand the subtly disguised tyrannies which sprang or were about to spring from New Left sources overseas. Political correctness was merely the first of such tyrannies which have attempted to warp and otherwise undermine Western life.

As noted American cultural commentator Roger Kimball has remarked: ‘It has been in the life of art and the life of the mind, however, that the counterculture has had its most devastating effects. To an extent which would have been difficult to imagine thirty years ago, art and education have become handmaidens of political radicalism… Colleges and universities, aping this exhausted radicalism, have given themselves up to an uneasy mixture of politically correct causes and the rebarbative rhetoric of deconstruction, poststructuralism and “cultural” studies’. Sadly, what he is commenting on here so unfavourably remain ‘flagship’ courses in neo-Marxism, in fact. So why does so much of Australian academic life continue to pay daily homage to a discredited system?

The so-called ‘Long March’ envisaged by Gramsci, Marcuse and other Marxist hardliners has taken Western society and academic life just about as far as it can possibly go now in a misguided and largely destructive direction.

So how about marking 2017 in Australia with a hugely overdue turn-around in our national academic and cultural priorities? No more appropriate memorial could exist for the millions who died or were hideously oppressed by communist ideology for an entire, misguided century.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in