Artists, poets and philosophers have not paid much attention to Milton Keynes …although comedians have. This urban experiment has been mocked by lazy satirists who find ambition derisory and concrete cows hilarious.

Milton Keynes is 50 this year and it has an honourable place in the history of that ancient chimera, the Ideal City. It was conceived in a decade when the improving influence of the ‘white heat of technology’ could be cited without irony (or embarrassment). In those days, technology involved calorific value, not cold, invisible bytes.

The name sounds like an ad-man’s invention. But until 23 January 1967, when the new city was designated, Milton Keynes was an old, quiet Buckinghamshire village near Bletchley, one of 15 that were absorbed into the whole. Its history involves utopias, the picturesque, Garden City idealism, a naive infatuation with America and a quaintly touching faith in the possibility of a tolerable future. Given the government’s recent announcement of the creation of 14 ‘garden villages’ (for what appears to be a bargain price of £6 million), it’s instructive to reflect on how Milton Keynes became very nearly, but not quite, the world’s greatest example of new place-making.

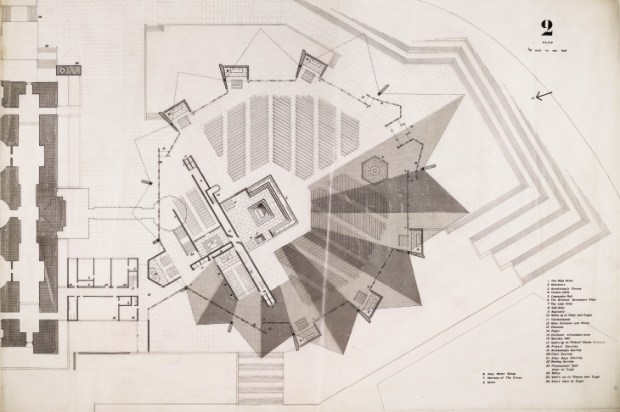

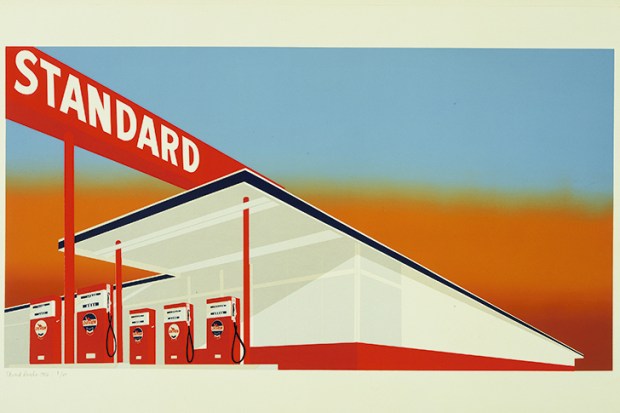

Hippy architects were crucial to it — they aligned the central boulevard with the trajectory of the sunrise on the summer solstice. But cars were even more fundamental to the Milton Keynes idea. Indeed, 1967 was something of a miracle year for the automobile with the launch of the technically advanced NSU Ro 80 and the Saab 99. You can still smell the fumes. The plan of the new city was drawn up when the 1963 Buchanan report, Traffic in Towns, was still a white-hot intellectual property. Addressing the minister of transport, Ernie Marples, Buchanan explained: ‘We are approaching the crucial point when the ownership of private motor vehicles, instead of being the privilege of a minority, becomes the expectation of the majority.’ In the days when architects and planners routinely went to the United States for their inspiration (Norman Foster and Richard Rogers both had fellowships at Yale in the Sixties), Buchanan wanted to see more motorways modelled on the American interstate network.

That transcontinental dream was only partially realised in our shabbily apologetic motorway system, but another idea in the Buchanan report accurately predicted the Milton Keynes plan: ‘The future pattern of cities should be conceived as a patchwork of environmental areas.’ Which is to say, traffic-free zones connected by roads. This was also the idée fixe of the Californian planning theorist Melvin M. Webber, the true father of Milton Keynes. Webber’s vision was that modern telecoms and cars made citizens infinitely mobile, so the traditional notion of the concentric city with a core was irrelevant. Instead, it was to be atomised: ‘community without propinquity’ was Webber’s catchphrase.

Thus, Central Milton Keynes, always known as CMK, was a commercial centre only. Forget for a moment that the unusually articulate town planner Francis Tibbalds called it ‘bland, rigid, sterile and totally boring’: it was designed by architects who, innocently, revered Chicago. The residential part of the city was laid out on a grid of horizontal and vertical roads at one kilometre intervals with many, many roundabouts. These roads did not run through the independent communities within the grid, but connected them, as Webber had insisted.

If this sounds lamely in thrall to the automobile, the original planners also said that no building should be taller than the tallest tree and there was even ambitious talk of making a ‘forest city’. And architects of real ability — including that same Foster as well as Ralph Erskine and Richard MacCormac — were eventually chosen to give individual identity to each separate community with, it must now be admitted, only partial success. That said, the Chinese regularly send their city planners here to take notes.

Snobbery about Milton Keynes takes no account of its utopian spirit. This idea of designing a perfect community is as old as history itself. It’s a long journey from Hesiod’s Golden Age to the Buchanan report and in between you find Plato and Thomas More. Not to mention Tomasso Campanella, whose influential La Città del Sole (1602) suggested a perfectly managed city where, for example, sodomites walk around with shoes around their necks to show how little they understood the natural order. Granted, concrete cows are a poor alternative.

Then there is that distinctive English contribution to world architecture: the city and the town harmoniously combined. From John Wood’s Habitations of the Labourer (1781) to John Nash’s 1812 report of the Commissioners of His Majesty’s Woods, Forests and Land Revenues, which gave us the incomparable Regent’s Park, and on to Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City movement, English town planning was a world exemplar. True, the French had their planning theorists in Saint-Simon and Fourier, but their visions were unbuilt.

The problem with Milton Keynes is that, for all its good intentions, newly fashionable ideas that could have improved the city were ignored. So, too, was beauty: exit at junction 14 of the M1 and the vista could not be confused with, say, Federico da Montefeltro’s Urbino. When New York decided on a grid plan in 1811, having considered alternatives with star shapes and ovals, it was not on account of idealism, but economy and convenience. But, in the end, that loose-tight structure actually encouraged extraordinary architectural improvisations. In Milton Keynes, the isolated communities have remained exactly as they were on the original plan. Of benevolent organic growth, there is little to say. Probably cities need to be more messy to be good.

The very year when Milton Keynes was designated, Edmund N. Bacon, who saved Philadelphia from roughneck redevelopment, wrote a memorably simple line about city building: ‘One of the prime purposes of architecture is to heighten the drama of living.’ Buchanan had a conclusion too: ‘The freedom with which a person can walk about and look around is a useful guide to the civilised quality of an urban area.’ With only those ideas in mind, Milton Keynes failed.

Today you drive around the city, dazed by the roundabouts and musing that it is not quite the exciting urban forest that was promised. Or you get off the train and stare glumly at a bleak Soviet parade ground. Perhaps Tibbalds was correct when he said that Milton Keynes is not ‘awful’, but ‘disappointing’: yet to cite disappointment is evidence of high ambition. You’d have to be an insensitive brute not to sense the touching idealism of it all. After all, Milton Keynes was the scriptural home of the University of the Air which, as the Open University, established Massive Open Online Courses long before internet nerds appropriated the idea. My own first job was there and the sense of esprit de corps was absolutely real, even if the genius loci was already elusive.

Still, as London becomes dismayingly polarised between the nomadic international rich and an embittered indigenous underclass, maybe the disenfranchised youth and persecuted middle classes who are all plotting to leave the capital will see something inspirational in the Milton Keynes idea.

I know I do.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in