Arthur Rackham shouldn’t have lived in anything as conventional as a house. It should have been a gingerbread cottage, like the one he drew for Grimms’ Fairy Tales, with cakes for a roof and boiled sugar for windows. Or a Rapunzel turret, for letting down ropes of long, blonde hair, except he was so very goblin-bald. Or a Sleeping Beauty palace with a spinning-wheel in the topmost tower.

As it was, he lived in Chalcot Gardens, north of Primrose Hill and south of Hampstead Heath, with his wife Edyth Starkie, a portrait painter, and their daughter Barbara, at the end of an 1880s row set back from the road. It may not have been a fairy-tale castle (you don’t get many of those in Belsize Park), but it was distinct from its neighbours: an odd, square Voysey house, the sort that children draw, with a high, steep roof like a witch’s hat.

In the 15 prolific years Rackham lived there from 1905, strange things were summoned and conjured. Mad Hatters came to tea, mermaids found themselves beached on the studio floor, geese laid golden eggs, Gulliver surveyed the troops of Lilliput and the Pied Piper played his tune. Rackham marshalled them, not with a long trilling pipe, but with pencils, brushes and watercolours. In a portrait of 1924, when the illustrator was 57, he painted himself against the Thames, his spotted tie neatly knotted, and his pencil sharpened to a spinning-wheel’s point.

Rackham, who celebrates the 150th anniversary of his 1867 birth this year, had to be tidy to keep his sprites and fiends, elves and fairies, giants and wolves, sacred crocodiles and stoned caterpillars, in order. The munchkins and mischiefs of his imagination — more than 3,000 sheets of them over a lifetime, some with as many as 50 rioting hobgoblins to a scene — would have run away with him if he’d let them. So he balanced rabbling goblin markets on the page with order in the studio and in life. He was tidy, thrifty and cautious. He recycled old newspapers into blotting paper, into wrapping paper, for keeping warm in bed, for drying damp shoes, into a tablecloth to catch the oil and flakes from sardines.

He did not smoke. His favourite meal was cold roast beef. He drank little, but in later life allowed himself a small nightly glass of Marsala. He was thin and had the same slim suit made and remade by a tailor each time it wore out. Not very bohemian, not very Beardsley.

He played golf and wore steel-rimmed spectacles. A pair for reading, a pair for tennis, a pair of bifocals for careful work. He always had a hot Thermos for a cold train. He did smash a few plates to get the detail right in his Alice in Wonderland (1907) illustrations. Doris Dommett, the little girl who modelled for Alice, asked of the Rackhams’ cook: ‘Will she throw plates?’ ‘Oh no,’ said Rackham, ‘they’ve already been thrown.’

When asked to celebrate his art — his trade, too, for he took on more ‘pot-boiling’ hackwork to pay the bills than he would have liked — for the Old Water-Colour Society’s Club, he wrote this: ‘From the first day when I was given, as all little boys are, a shilling paint box with the legend printed along the space for the brush — “Waste not, want not” (so I was informed, for I couldn’t read then) — from that day, when I first put my water-colour brush in my mouth, and was told I mustn’t, this craft we are celebrating has been my constant companion… Such a modest silent convenient companion too.’ Modest, silent, convenient. Waste not, want not.

Did he want to join them? The Mad Hatters and March Hares and Toads of Toad Hall? Again and again, he sneaks into the stories. When Scrooge’s doorknocker takes on the face of Marley in A Christmas Carol (1915), it is Rackham’s face, spectacles propped on the top of his head. Gulliver borrows Rackham’s specs to view the fleet in Gulliver’s Travels (1900). The skinny Jack Spratt of Mother Goose (1912), wearing spectacles and wrinkled stockings, is Rackham again. The Mad Hatter has the sloping Rackham nose.

On many writer and artist anniversaries we have to do a recovery job: ‘the unfairly neglected Rumpelstiltskin’, ‘the out-of-fashion Miss Muffet’, ‘the ripe-for-revival Tom Thumb’. With Arthur Rackham there is no restitution to be done. He has never gone away. Children are still given Everyman Children’s Classics by god- and grandparents on their birthdays and Rackham has become a hero of the adult colouring-book market in colour-your-own editions from Pook Press.

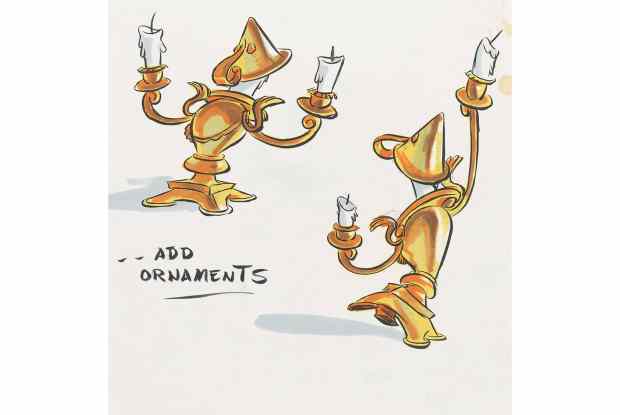

He has been made and remade by others. He is there in the films of Max Reinhardt and Lotte Reiniger, and in the romances of Walt Disney. Rackham family myth has it that Disney invited Rackham to California in the 1930s to work on Snow White, but no biographer has yet found the letter. California or not, Disney’s princesses — Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Belle, Ariel — are Rackham princesses. They have the tiny waists, tapestry grace and heart-faces of Rackham’s siren-heroines.

Rackham, for all his fastidious, bow-tie niceness, could do gorgeous. To get the tail-swish of his slinky mermaids and Rhine-maidens right, he had his models pose nude, suspended on a trapeze from the studio ceiling. The fairies for Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906) flounce in off-the-shoulder gowns. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1908), Titania nuzzles Bottom’s great ass’s head, and knots her fingers through his mane. There is something sexy indeed about the 12 pairs of spent satin slippers, kicked off on the bedroom floor by the Dancing Princesses when they return from a night’s waltzing.

Would there have been a Biba without Rackham’s rich stuffs and embroideries, or a Laura Ashley without his barefoot gypsy girls and Tattercoats? He is there, too, in the work of contemporary fashion photographers Tim Walker and Mert Alas & Marcus Piggott with their living dolls and Red Queens.

He is there in Harry Potter, in the walking trees of Lord of the Rings and, inescapably, in the films of Tim Burton. There is not a frame of Burton’s Sleepy Hollow that hasn’t a Rackham tree — he illustrated the Washington Irving story in 1928 — stretching bony twig fingers into the forest. Once you have seen a Rackham tree, leafless, reaching, clawing, you can never look at any tree at this time of year, black against a grey sky, and not imagine it twitching, not think of goblins in the branches and demons peering through the knots.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in