‘Oh, some of my films have been attacked with absolute vitriol!’ said Nicolas Roeg, 85, and still one of the darkest and most innovative of post-war British directors. We were sitting in his study in Notting Hill; nearby in Powis Square is the house Roeg used for his 1968 debut, Performance, starring Mick Jagger as the rock star who entices a gangster (James Fox) into a drug-induced identity crisis. The film was shelved for a year before Warner Brothers dared to release it.

‘The critics didn’t always get it then — but they do seem to now,’ said Roeg.

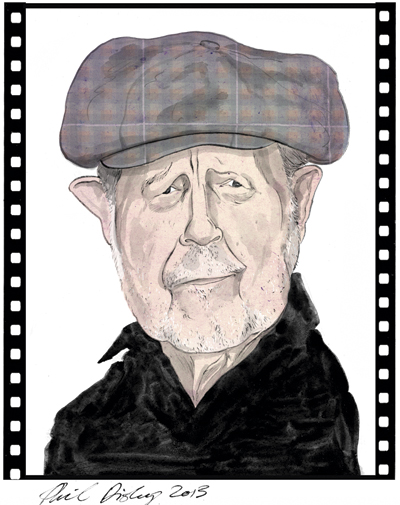

Roeg was born in 1928 in St John’s Wood into a vaguely bohemian background. A lifetime’s accumulation of books, awards and framed pictures of his former wife, the actress Theresa Russell, spills into the room. Roeg, a rumpled, softly spoken man with a very English reserve, has just published a book of reflections on film, The World is Ever Changing, in which he chronicles (among other things) his ‘flawed life’ as a director.

‘I liked the book a lot,’ I said.

‘It’s very nice of you to say so. The last thing I wanted was to write an academic treatise or to lecture at the reader from the pulpit.’ Instead the book is tinged with a sense of amazement and the self-examination of an older man looking back on a most unusual career.

Roeg was eight when he discovered film. ‘Going to the cinema was an adventure. I was always a bit arty-farty as a boy. “Come on, Mr Arty-Farty,” my sister used to say to me.’ Babes in Toyland, with Laurel and Hardy, was the first movie to open up the ‘mystery’ to Roeg of celluloid make-believe. Roeg’s has always been a painterly imagination. In his immensely stylish The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), starring David Bowie as an extra-terrestrial in search of water for his drought-stricken planet, Roeg made an artist’s use of the parched hinterlands round New Mexico.

Bowie was reportedly on cocaine for much of the shooting. ‘Well, David’s performance was something quite unique. He never came on like a rock star — he used his part to explore ideas of rock idolatry and celebrity. David was very clever and creative in that way.’ Bowie’s 1977 album Low was intended partly as a soundtrack to the film, but Roeg chose not to use it. ‘It was better that way — the film was able to keep its integrity.’

Impressively, Roeg’s career spans half a century from his start as a clapperboy for MGM in 1950 and camera operator for such unlikely films as Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure. ‘I came up the old-fashioned way — tea boy, cutter, focus-puller, cinematographer — but I wasn’t myself old-fashioned.’ In the early 1960s Roeg worked for David Lean on Lawrence of Arabia and Dr Zhivago and, later, for François Truffaut.

Roeg’s best-known film, Don’t Look Now (1973), was a meditation on supernatural coincidence set in Venice, that still frightens like an unlucky number. With its use of swift cross-cutting and tumultuous imagery, the film radiates a fierce beauty and disquiet that could only be Roeg’s.

However, it was Roeg’s coming-of-age film Walkabout (1971) which made his name. I first saw it on television as a teenager in the mid-1970s; inevitably with my hormones fizzing I was struck by Jenny Agutter as the schoolgirl lost in the Australian wilderness. Agutter turned 17 during the shoot, Roeg recalled — ‘the same age as my granddaughter is now’. (Roeg has six sons and three granddaughters.)

I said: ‘My daughter saw Walkabout the other day and loved it.’

‘I’m so pleased to hear that. What’s her name?’

‘Maud.’

‘Maud! That was my mother’s name!… Or was it Mabel? Actually I think it was Mabel.’

(It was definitely Mabel.)

As a director, Roeg is concerned above all with the frailties of human desire. In perhaps the most notorious scene from 1970s cinema, Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie make love (supposedly for real) in Don’t Look Now before going out to dinner in their hotel. Their marriage has been put to the test by the death of their daughter in England but in sex at least they find a consolation. ‘The American censors put an “X” on the film because of that scene but there’s no seduction involved and it’s shot as a completely normal human event.’ Roeg added: ‘By the way, I hate the term “sex scene”. It suggests pornography, which 99 per cent of the time has nothing to do with the human condition. Yeats said that sex and death are the only things that can interest a serious mind, and I have to agree with him on that.’ Daphne du Maurier, on whose novella Don’t Look Now was based, wrote to Roeg to say how much she admired the film. ‘But foolishly I gave the letter away to a biographer, who never returned it.’

Roeg’s masterpiece is Bad Timing (1980); in a most disturbing scene, the American psychoanalyst played by Art Garfunkel has sex with Theresa Russell’s unconscious body after cutting away at her underwear with a penknife. The work was condemned by its distributor Rank as a ‘a sick film made by sick people for sick people’. Roeg, then 52, was already established as a film-maker in the visionary company of Powell and Pressburger, and cared little for box-office success.

His more recent work, with its trademark plot twists and disorientating camerawork, has been critically mauled at times. Only now can we see a film like Puffball (2007), based on Fay Weldon’s novel of the same title, as extraordinary and enduring.

‘You know, film remains completely mystical and mysterious to me,’ Roeg said to me as I left, still smitten after all these years. Out in the July sunlight again, I felt grateful to have met this last true magus of the silver screen.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

The World is Ever Changing by Nicolas Roeg is published by Faber.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in