What, really, is a literary education for? What’s the point of it? How, precisely, does it help when you’re another day older and deeper in debt?

These are questions that after a while begin to present themselves with uncomfortable force and persistence to those of us who have believed from our earliest youth that if literature will not save us, it will, surely, at least do us some small, perceptible good. What answer can we make, surveying the ruins?

Nicholas Lezard is useful here, as a test case, a case tested to destruction even. Not only does he have a thoroughly literary turn of mind, he is, as he says, probably the last remaining person in the world who makes ‘what could loosely be called a living from reviewing books’.

He has for several years also been writing a column in the back of the New Statesman called ‘Down and Out’ describing his misadventures in a slummy flat near Baker Street, which is, apart from the contributions of one or two of its arts critics, the main attraction of that otherwise hopelessly confused magazine.

Bitter Experience Has Taught Me is a lightly revised gathering of the first 90 or so of these pieces, and it is a delight, a book so funny it helps you understand what it means to be exhilarated: to have your whole mood lifted, to take your own sorrows more lightly.

If there was a precursor for this column, it is the much missed Jeffrey Bernard, who actually began it in the Statesman, as Lezard dutifully points out:

As it happens, I used to hang out with Bernard, to the point that he had the sauce to pinch a girlfriend off me; she came back after a brief interval, during which she discovered that diabetic alcoholics who drink a bottle of vodka a day can have problems in the sack. But that’s another story for another day.

Lezard himself claims to stick to the ‘iron rations’ of no more than a bottle of wine a night, although I suspect that that may be an underestimate; or perhaps he means one of those plus-sized bottles named after a card from the Old Testament.

However that may be, or whatever other misdemeanours he committed, five years ago, aged 45, he was summarily sacked by his wife and cast out of the family home to become yet another derelict middle-aged man. Now he lives in ‘the Hovel’, mostly shared with a friend called Razors, and he is vigorously pursued by the taxman. He has no money and his post-marital lovelife does not go smoothly.

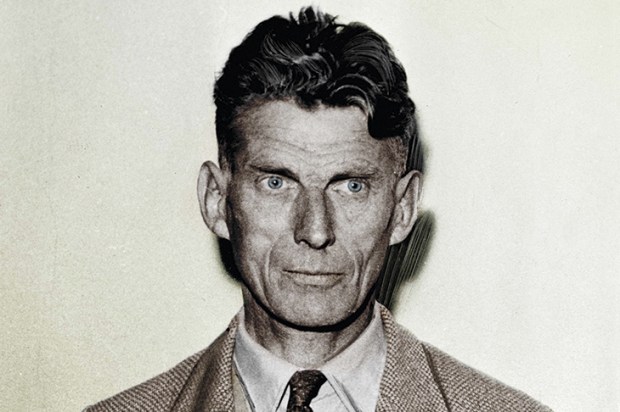

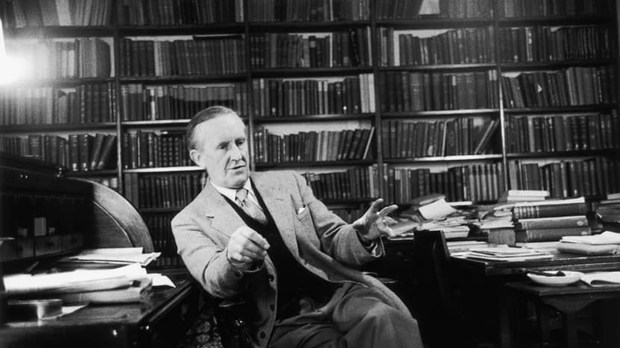

Sometimes he describes real unhappiness, but he does so in such high style that it is still a pleasure to read about. Indeed the routine disparity between the poverty of his situation and the lavish provision of his language is funny in itself. For, as a prose stylist, Lezard is the bastard offspring of a previously unsuspected union between P.G. Wodehouse and Samuel Beckett, mixing the eloquent inventiveness of the former with the sudden nihilism of the latter.

Both of these idols are constantly invoked here, in the interests of seeing his situation as comic rather than pathetic. Perhaps Lezard even takes them too seriously? At his lowest point after separation from his wife, he says:

Wodehouse, at the moment, is causing me a lot of problems. His world is indeed Edenic, prelapsarian; but I find myself taking his deliberately silly love plots seriously, and becoming enormously fretful about the prospects of his characters’ problematic engagements. Please, I say to myself, the tears welling in my eyes, let it all work out for Bingo Little. And Bertie, what is so bad about Florence Cray? At least you will have in her a woman who cares whether you are dead or alive.

He brings, you see, a developed style, not to mention an apt allusion, to every problem. He is equally funny here about rail replacement buses, instructions for a toaster, being dumped, and his filthy fridge, which he suggests should have a note stuck on the door saying: ‘The smell you will experience on opening me may as well be a symbol for the Augean stables of your existence.’

Literature may not have saved him, it may have actually led him to destruction, but it has helped him to see the joke. Can we ask more?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in