It’s been a sensational week for opera in London, with a sensationally good performance of Strauss’s Elektra at the Royal Opera, and a sensationally terrible production of Fidelio at English National Opera. Charles Edwards’s production of Elektra is revived for the second time, but this is quite the finest account of it, thanks above all to the conducting of Andris Nelsons and the assumption of the title role by Christine Goerke.

This opera can, and usually does, remind me of lying on the road under a deafening drill, and reinforces my admiration for the tact with which Wagner places his climaxes. Nelsons, having dealt a hefty blow with the first chords, then managed the dynamics with extraordinary skill, providing plenty of respites both for the singers and the audience. Not, I suspect, that Goerke needs respites. She has a huge voice, absolutely steady throughout its range, and she seems one of those artists, like Astrid Varnay and Birgit Nilsson, who is destined for or doomed to this role. Her timid sister Chrysothemis seems a perfect role, too, for Adrianne Pieczonka. The only lead I had any doubts about was Michaela Schuster’s Klytämnestra, who seemed inadequately raddled, in fact in quite good shape, and, for my taste, didn’t ham sufficiently in a role that screams for it; and surely a part that consists largely of retailing nightmares and envisaging assault and death should sound less mellifluous? Iain Paterson’s Orest was so noble that I expected him to become the Wanderer in Siegfried at any moment. Still, musically the cumulative impact was immense, and triumphed over the rather vague setting and direction.

This production is set in 1900s Vienna, with a revolving door but no café, and some ancient Greek ruins. Costumes are more or less Klimtian, though Elektra wears a timeless loose black dress. Quite a lot of the text must seem gibberish to anyone who isn’t used to opera productions that ignore the passage of time, though Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s adaptation of Sophocles does largely remove the theological dimension of the work, thus making it morally and psychologically incoherent. In other words, the characters almost all seem mad, whereas in Sophocles they are not only continuing a family saga in which Agamemnon appears in no good light, but they are also behaving as they do because of their relationship to the gods and to concepts of eternal law and justice. But, given Strauss’s temperament and the nature of his talent, it was probably a good idea for him to stay in the purely human world of psychopaths and neurotic cripples.

It is a commonplace that Fidelio is a problematic opera, thanks partly to the naïveté of its text and more to the simple-mindedness of its central ideal of freedom. Yet in a straightforward production, or when you listen to a fine performance on record, those problems and any others disappear in the overwhelming nobility and generosity of Beethoven’s vision. What Calixto Bieito has done, first in Munich and now at ENO, is to interfere radically with the work and thereby, according to his disciples, simultaneously share and undercut Beethoven’s vision. You can’t do both. The place to undercut, deconstruct, interrogate, contest (or any other cant term one might care to use) is in an article about the work or about a production of it. What anyone who misguidedly goes to this Fidelio will see is not a drama at all, and certainly not Beethoven’s.

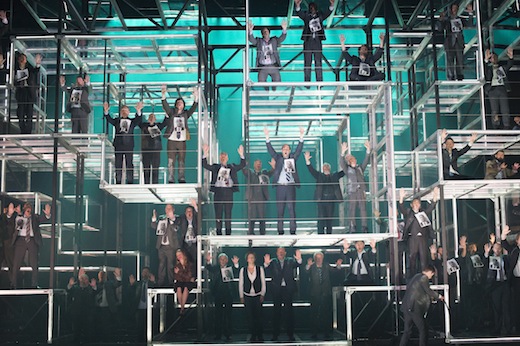

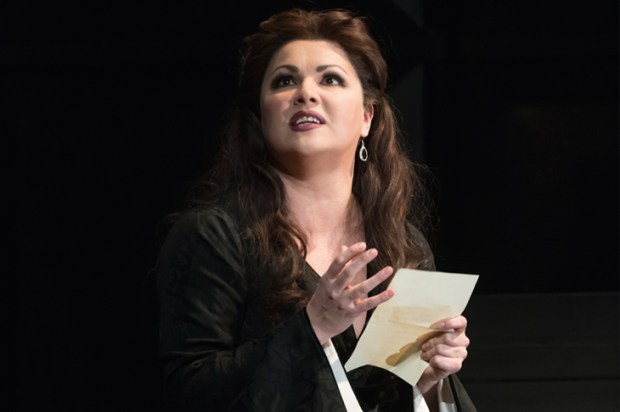

Fidelio by Beethoven at the London Coliseum Photo:Tristram Kenton

Fidelio by Beethoven at the London Coliseum Photo:Tristram Kenton

It opens with our being blinded by a set of neon-lit cages, while Emma Bell, who plays Leonore, says something too quiet for most people to hear. The Overture that follows is Leonore No. 3, which, as Wagner pointed out, makes the ensuing drama largely redundant. We got a good sample here of Edward Gardner’s conducting: swift, a lean sound, decidedly meagre lower strings. Those features persisted throughout, so that mainly the musical reading was superficial. But that was the least of my problems. All the dialogue was cut, and, stilted as it may be, it does efficiently lead from one musical number to the next, as well as giving us a clear idea of the narrative.

In Bieito’s Fidelio, a quite separate thing, we get mystifying snatches of Borges and Cormac McCarthy. Nor is David Pountney’s ‘translation’ of the sung text any help. It is a strange mixture of styles, and not easily singable. Enunciation is on the whole poor, with Bell singing her heroic part beautifully but unintelligibly. Stuart Skelton is much better in that respect, and his singing of his aria was the musical high point of the evening. After he had been rescued — by Leonore pouring acid over Pizarro, who had gone in for self-harming while singing his aria — and the happy pair had changed into evening wear (a wretched touch), a string quartet came down in three glass containers and played the slow movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet opus 132, omitting the andante sections: very moving, but quite extraneous to what we had seen and heard onstage. The coup de disgrâce was the appearance of Don Fernando dressed as a ludicrous fop, singing the score’s most solemn music and shooting Florestan, who was resurrected by Leonore. Need I go on?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in