Shortly before his death, David Frost rang to ask me to take part in a radio series he was making to mark the 50th anniversary of ‘the year, Chris, that I know is closest to your heart, 1963’. This was not because 1963 was the year when he and I worked together on the BBC satire show That Was The Week That Was (TW3), which overnight made Frost a television superstar. It was because he remembered the importance I had given to the events of that year in The Neophiliacs, a book I wrote long ago analysing the tidal wave of change which swept through British life in the 1950s and 1960s.

By any measure the stream of scandals, shocks and sensations which poured through the headlines in 1963 made it as extraordinary a year in Britain as any since the second world war. Recent books, films and articles have recalled some of the individual events of those surreal 12 months — the worst winter for 200 years, which covered Britain in snow from December to March, the Profumo scandal, the Great Train Robbery, the explosive rise of the Beatles, Harold Macmillan’s dramatic exit from the political stage. In recent days, we’ve been treated to lots of recollections of that year’s most sensational event, the assassination of President Kennedy.

What has been lacking, however, is any real attempt to put all those individual dramas of 1963 together, to show just why they made it such a watershed year in Britain’s postwar history. The reason it took up an entire chapter of my book was that it marked the moment when the ‘old order’, which had for so long seemed to be at the core of our national identity, finally crumbled, giving way to the very different kind of country that in many respects we still live in today.

There is no better measure of the pivotal importance of 1963 than to recall what Britain was like in the early 1950s, as we slowly emerged from the shadows of the second world war. The great Labour experiment of 1945 had petered out in a grim slog through years of austerity and rationing. With Winston Churchill back in No. 10, life had begun to crawl back to ‘normality’. Conservative values ruled: respect for tradition, discipline and authority. The old class structure still stood. No extramarital sex or homosexuality. In the cinema we were entertained by cosy Ealing comedies and films portraying the ‘stiff upper lip’ spirit which had won the war. Pop music, hardly ever allowed on the BBC, centred on crooners such as Frankie Laine and adaptations of folk songs. The pomp and pageantry of the Coronation in 1953 reminded us how Britain still stood proudly at the centre of a worldwide empire.

Between 1955 and 1957, however, this complacent mood was rudely challenged by the first harbingers of a different world to come — commercial television, the great rock’n’roll craze inspiring a new ‘teenage culture’, ‘Angry Young Men’, the humiliation of Suez. As this turbulence died away, the British in the late 1950s sensed that they were being carried forward into a wholly new kind of future, the ‘age of affluence’. Television had moved to the centre of national life. Traditional moral values were losing their hold. But no one seemed more successfully to ride this ‘wind of change’ than the new Conservative prime minister, Macmillan, hailed as ‘Supermac’, winning in 1959 a landslide election victory and the following year coining that very phrase, to reflect the speed at which Britain was divesting herself of her colonial empire.

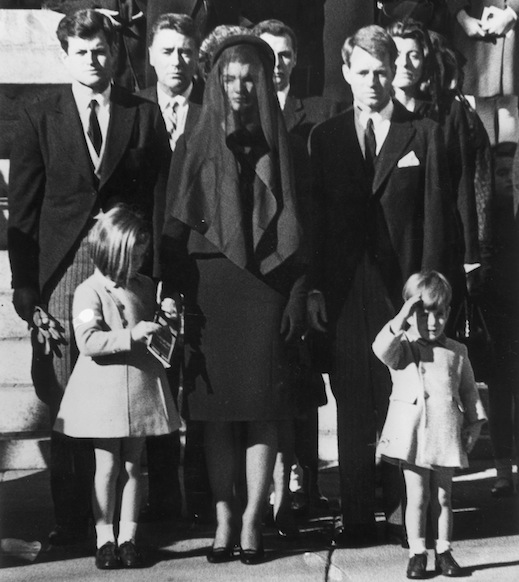

By 1960 the sense that an unprecedentedly hopeful new age was dawning was nowhere better symbolised than in the election of John F. Kennedy as the youngest US president in history, to become the new decade’s first towering ‘dream hero’. But no sooner had Macmillan made in 1961 his most daring move to break with the past, by bidding to take Britain into ‘Europe’, than the mood again abruptly changed. Suddenly, not least in contrast to Kennedy’s youthful glamour, the ageing Macmillan came to be seen, by a new generation of young satirists, as an upper-class Edwardian relic, quite out of touch with the new world. Catching the same irreverent spirit were an unknown group of young Liverpudlians singing rock ’n’ roll in Hamburg nightclubs. By the end of 1962, as a former US secretary of state proclaimed that Britain had ‘lost its empire and not yet found a role’, in a country now increasingly scornful of all those traditional values and assumptions which had been losing their grip, the stage for the watershed year of 1963 was set.

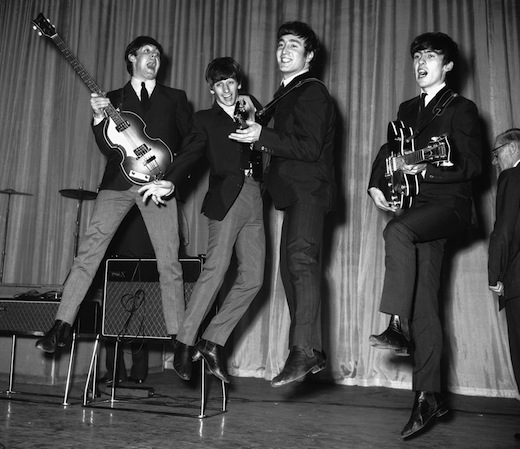

Many people were to remember the winter of 1962-63 above all for three things. One was the hypnotic popularity of TW3, the BBC’s new Saturday-night satire show, ridiculing politicians in a way which in the deferential 1950s would have seemed unimaginable. Another was the first appearances in the record charts of the Beatles, unlike any pop group heard before. The third was the blizzards which buried the country under snow for nearly three months, bringing havoc to almost every form of human activity.

One shock at this time was the death at only 54 of the Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell, succeeded by a man more attuned to the spirit of the age, Harold Wilson. Another was the slamming of the door by President de Gaulle on what had become Macmillan’s flagship policy, his bid to join the Common Market. A third was Dr Beeching’s bid to drag at least one of Britain’s failing 19th-century industries into the modern age, by closing down half our railway stations and scrapping the steam engines which for more than 100 years had been such a proud symbol of the country where they were invented.

It was also at this time that the first rumours began to swirl around London of an immense web of sexual scandal, involving not just one of Macmillan’s ministers but numerous other members of the establishment and the upper classes. The significance of what was eventually to break surface as the Profumo affair was that it bore little relation to the comparatively trivial sexual misdemeanours that had given rise to it. It was seized on with glee as a shadowy indictment of Britain’s entire ruling order.

What might have made this seem incongruous was that Britain was now meant to be enjoying a full-scale ‘permissive revolution’: the ‘New Morality’ being celebrated at this very time by a Bishop of Woolwich who three years before had given evidence in favour of allowing four-letter words to be published in Lady Chatterley’s Lover and whose book Honest to God, ditching the Ten Commandments, was now topping the bestseller lists.

When in June John Profumo confessed that he had lied about his brief fling with Christine Keeler two years before, as I wrote later, ‘all the swelling tide of scorn and resentment for age, tradition and authority, all the poisonous fantasy of limitless corruption and decay into which it had ripened, were finally unleashed in their full fury’. So bewildered was Macmillan by the madness of this new age that he could only brokenly stammer to the Commons: ‘I do not live among young people fairly widely.’ For weeks the hysteria raged on, culminating in the trial and suicide of Stephen Ward, after no evidence had been produced to support the charges on which he was about to be found guilty.

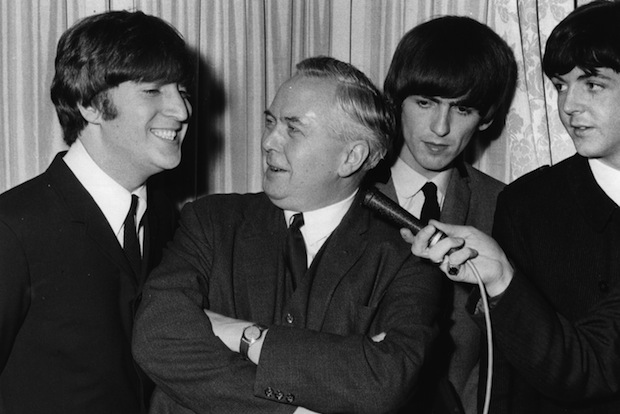

Almost immediately the headlines were again filled for days with news of the Great Train Robbery, a crime so daring that its perpetrators were portrayed as heroes. But even more obsessing the public now, as their fourth record ‘She Loves You’ topped the charts for seven weeks, were the Beatles, so hypnotically glamorous that they had joined Kennedy as the supreme ‘dream figures’ of the decade.

At October’s Labour conference, the ‘class-less’, ‘dynamic’ Harold Wilson united his fractious party round a nebulous vision of ‘the technological revolution’ and ‘coming to terms with a world of change’. The Tory conference was stunned to hear that Macmillan, his health broken, had resigned, plunging his party into a hysterical leadership war which, to universal astonishment, resulted in his succession by the 14th Earl of Home. TW3 greeted this with a sketch so contemptuous (alas written by me) that, after the BBC switchboard had been paralysed by an avalanche of protests, a panicking director-general decided that the show must be taken off the air.

Labour raced towards a 20 per cent lead on the polls. In November the Beatles, greeted by thousands of screaming teenage girls, stole the show at the Royal Command Variety Performance. On 22 November the shock news flashed round the world that Kennedy had been murdered. It was the only sensation which could have outstripped all the rest. In December a special edition of the Evening Standard summed up 1963 as having been simply ‘The Year of the Beatles’.

Niagara had been shot, ‘Old England’ was dead. The following year ‘Swinging London’ was being hailed as ‘the most exciting city in the world’. Bringing an end to ‘13 years of Tory rule’, the ‘dynamic’ little poseur Harold Wilson — a proto-Blair — strode proudly into No. 10. The new world we have lived in ever since had been born.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in