Laikipia

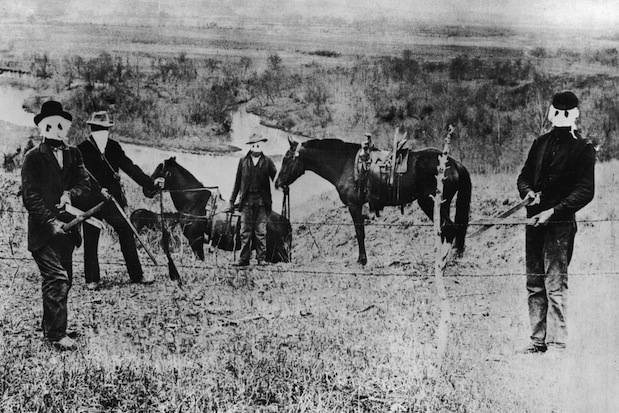

In the cattle rustlers’ camp, I know as I write this that the warriors are sharpening their blades, staring down the dirty barrels of their rifles, and loading their clips with bullets. Before full moon on the 17th of this month they will set out in their war paint, glistening with rancid butter and ochre. There will be four of them, young men not much more than teenagers. One will carry a bucket of sheep’s fat, and on this disgusting ration they will survive while lurking in the thorn scrub for days, never making a fire, leaving no tracks, sleeping cold on the rocks — and watching us.

They will watch us as we go about our daily routines. They will observe the cattle as they emerge from the boma night enclosure as the askaris let them out at dawn to graze and the animals spread out across the plains. They spy on the herds as they water at the springs. They crawl up close enough to see if the cowhands are armed, or if they carry radios. They can see which cattle are easily driven, the fattest steers, the ones that are sturdy enough for the long stampede. At the same time, they look at the ones that are to be avoided because they seem aggressive, or have calves at foot, the ones that will not run. Before dusk, when the animals return to the big stone boma, the bandits will see how the cattle are shut in with two sets of iron gates, three padlocks on a big chain and then coils of razor wire blocking the entrance.

I know what happens next and how things unfold because we’ve now been raided six times this year, during robberies in which dozens of bullets have been fired each time. Christmas is the worst time of the year for rustling because the police tend to be off napping, while even bandits want to enjoy the holidays by feasting on mountains of beef. We are on such high alert as we enter these holidays that I think if Santa Claus tried to make a delivery he’d be shot before he made it to the chimney.

But that will be unlikely to scare off our rustlers, who are brave enough to strike under cover of darkness. A night or two after full moon, they will attack, just as the herders are hanging up their boots and twiddling their toes by the campfire. A couple of bursts of AK-47 fire is enough to send the men scurrying for cover and as one or two gunmen stand ready to fire at anybody trying to return, two other bandits run up to the boma gate and start hammering at the padlocks with their knobkerries. I’ve been through just about every type of padlock on the market. I think I have found a make that is almost unbreakable — and the thieves have three of them to get through. At some point they might give up and start breaking the sturdy dry-stone wall that forms the boma perimeter. This is a formidable barrier to thieves, but not impenetrable. This week we had a leopard leap into the boma again, drawn by the scent of blood and afterbirth from a calf that was only a few minutes born and lying next to her mother. The leopard pounced on the little creature and half-devoured it within minutes.

It might take 15 minutes or more to break down the wall. All this time we will be regrouping. The armed askari, a determined man no more than five foot in height, will hopefully open up with his semi-automatic rifle, firing in the air. Last month he emptied the entire clip in several bursts, almost herding the bandits away as they returned fire in a desultory attempt to fight back. But if the bandits get through that wall they will drive out as many cattle as they can in a mob, running them as fast as they can go. Then we lay ambushes along their route, hoping to peel cattle off from the main group in a confusion of gunfire and shouting. Last week my neighbour had 40 cattle stolen long before dusk and they headed out across plains that are so wide they could not even be spotted from a circling aircraft.

Once the cattle are off the farm, vanished into the night, there will be nothing left to do but follow up on the tracks, a job that has become a familiar routine for us. Night-vision binoculars, extremely powerful torches, trauma medical kits, survival manuals and sleeping pills — these are the sorts of presents I get at Christmas, from concerned relatives who have become used to my holiday nerves. I hope my vision of that gang of rustlers trekking towards my boundary is wrong for once, but I will be eating my turkey half-listening for gunfire on the hill.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in