It has been a bracing start to the year at English National Opera. David Alden’s production of Peter Grimes, praised to the skies for the musical performance under Edward Gardner, returned to the Coliseum. Next up is Rigoletto (reviewed on page 50), directed by Alden’s twin, Christopher. Then comes Rodelinda, in another new production (or co-production, as is often the way these days) by Richard Jones.

Audiences will be particularly keen to see the Rigoletto, and not shy of making comparisons with the celebrated production by Jonathan Miller, which has finally been stood down after three decades. Hanging over everything, though, is the realisation that Gardner’s time at the helm is drawing to a close. Next summer the music director will end an eight-year term in the post before taking up the principal conductor’s position with the Bergen Philharmonic, which occupies a position in the second division of European orchestras. That is not to belittle the Norwegians. But Bergen is not Berlin or even Birmingham, where Gardner is currently the principal guest conductor of the CBSO. Why could he not have combined the two positions? Clearly he felt his race was run.

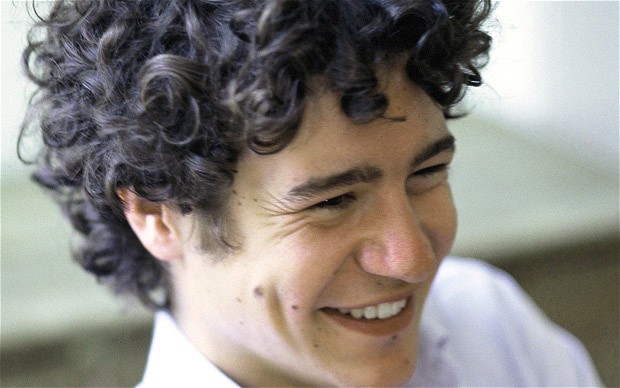

The new man, appointed last month to a few raised eyebrows, is Mark Wigglesworth. Two decades ago, after he had won the Kondrashin conducting competition in Amsterdam, Wigglesworth worked regularly with the great orchestras of Europe and America. This month he can be found in the boondocks of Colorado and Utah. So when his position was announced last month, people looked at each other and wondered: ‘Is this Granada I see, or is it just Asbury Park?’

Gardner leaves ENO with his reputation enhanced but with the house in a state of arrested development. This is not the chaos of a decade ago, when Oleg Caetani’s appointment as music director was rescinded before he had climbed into the saddle. Gardner, it is agreed, has been good for the company, and there have been a few hits along the way. There have also been misses, rather too many for the ENO’s reputation. The question is being asked once again: with an international opera house only a six-iron away at Covent Garden, what is ENO for?

An advertising slogan used to proclaim that ENO was English, National and Opera. Yet the productions frequently feature foreign singers when there are plenty of good native ones. Opera is a collaborative art form, of course, and nobody wants to set up a Checkpoint Charlie in St Martin’s Lane. But, when the role of Ellen Orford in the recent Grimes is taken by a South African, there is bound to be some muttering: can’t we cast a role like that from the home team?

Some things English, it must be said, should never have got approval. As much as it would like to attract a younger audience, ENO ought not to have given house room to something like Dr Dee, the ‘opera’ by the pop star Damon Albarn, which was essentially a vanity project. There are those who recall, through clenched teeth, the Gaddafi opera presented in 2006 by Asian Dub Foundation, described at the time by John Berry, ENO’s artistic director, as ‘groundbreaking’. It was, by Jove! But there is some ground that is simply not worth breaking.

An opera house should never apologise for being what it is, or bend to what others may want it to be. The best way to attract younger audiences to an art form that, of necessity, appeals to a discriminating élite, is to do good work, without embarrassment. That means engaging top-class conductors and singers, and hiring directors humble enough to recognise that the composer must always come first. Good composers help, too. We’ve heard enough Philip Glass for one lifetime.

The best answer to the charge of ‘élitism’ came years ago from San Francisco. Lofti Mansouri, then the general manager of the opera house there, flicked aside inquiries about the search for more socially ‘diverse’ audiences by saying: ‘I am not concerned with trying to attract people who are uninterested in opera. I am concerned with appealing to those people who are.’

That’s a good place to start. And if it means that ENO audiences are deprived of future productions by Calixto Bieito, that is something they will take in their stride. Let us do away with Regietheater, and the upside-down world of ‘concepts’. From Monteverdi to Mark-Anthony Turnage there is enough work for an opera house to present without recourse to the predictability of bogus radicalism. Masterpieces are not there to subvert; they are there to explore.

And so to Wigglesworth, who will be a youthful 51 when he succeeds Gardner. It is a mighty challenge for him, and his accession may yet be the making of a talented man who has, for reasons he clearly finds strange, acquired a reputation of belonging to the Awkward Squad. Rather like Kevin Pietersen, the England cricketer sacked last month for disloyalty, he finds the collegiate approach is not always to his taste.

His days with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales ended in mutual bafflement. He wasn’t invited back to the Royal Opera after conducting Meistersinger, and exposure to Glyndebourne, just down the road from his home in Sussex, did not lead to a regular working relationship. Nor does he work with the leading British orchestras. Put simply, and it sounds brutal, they don’t want him back.

Then there was the botched business in Brussels. The management of the Monnaie theatre appointed Wigglesworth music director in 2007 but the musicians, who had not been consulted, rebelled and the appointment was scrubbed within a season. It will be a wiser man, therefore, who joins ENO next year knowing this opportunity is the best chance he will ever have to become the conductor he wants to be.

He knows the orchestra, having conducted Così fan tutte, Falstaff and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk there. Best of all, three years ago, was his handling of Parsifal, which earned glowing notices. There is no doubt about his talent. But he has to convince others, who might have preferred an expat conductor such as Graeme Jenkins or Ivor Bolton to have taken the job, that he is worth the bother.

Yet again ENO stands at the crossroads. Long-standing supporters, fed up with novelty and vulgarity, are drifting away, and Gardner’s loss is a more bitter blow than anybody is prepared to admit. The clock is ticking.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in