What should a writer write about? The question, so conducive to writer’s block, is made more acute when the writer is evidently well-balanced, free of trauma and historically secure. It is made still more urgent when that writer is solipsistic in tendency and keen to write, not about the world, but about perceptions of the world.

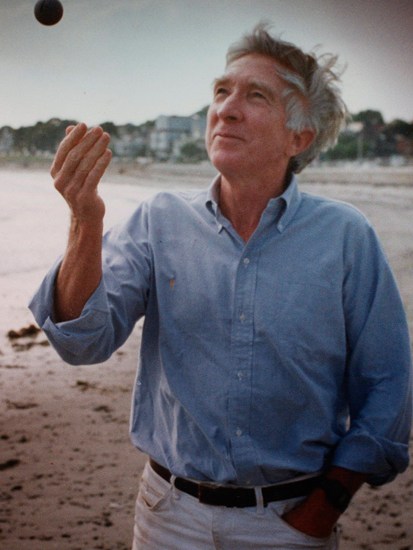

Two American authors of the same period arrived at different solutions to the problem. Sylvia Plath, in her husband Ted Hughes’s assessment, first found nothing worth writing about, and then deliberately encouraged demons and hitherto controlled minor difficulties until they flared up and killed her. John Updike, on the other hand, had an immensely long and sustained writing career, with few troubles to cope with other than psoriasis. His childhood was very happy, apart from a slightly disruptive move. As an adult, he met with immediate acclaim and success, which never entirely left him. What on earth was there to write about, to satisfy the immoderate itch that equally afflicts the talented and the untalented, the event-torn and the calm life?

Adam Begley’s interesting biography is largely an act of piety, but it may in the end contribute to the case for the prosecution. It begins with a truly startling example of Updike’s habitual creative process. A journalist came to interview him in 1983, and published the resulting article in the Philadelphia Inquirer on 12 June. Less than a month later, Updike published a short story in the New Yorker, efficiently translating the routine experience of being subjected to a provincial newspaper’s inquiries into well-turned fiction.

It was not a one-off. In 1972, for instance, a three-week vacation around the western states of America, in June, led to Updike ‘recycling his impressions in a short story — an expert distillation of the trip — and selling it to the New Yorker, which ran it in mid-August’. ‘Recycling’ is an odd word, used more than once by Begley, but not necessarily an inappropriate one. Sometimes Updike’s facility for transmuting experience into fiction was so great that he had to put the finished work aside to be published later — in the case of Marry Me, for 12 years.

This kind of efficiency has its advantages and disadvantages. Updike at his best resembles the visual artist he longed to be. Placed down in front of certain domestic circumstances, he sets to work evoking them in exact, lucid detail. He shares with his admired Henry Green a sense of the luminosity of things, though not Green’s virtuosity in dialogue, and his specificity can only come from a white-hot transcription of the immediate. When he writes, in Couples, of ‘A child of a cumbersome age, so wadded with clothes its legs were spread like the stalks of an H’, the sight is brought vividly before our eyes because it must have been so recently before the author’s own.

We are not going to disagree about Updike’s marvellous fluency, and when it meshes with one of the subjects that he found compelling, the results are masterly. The Rabbit books are great because their author found a way to direct his acute observing gaze through the sensibility of a man quite unlike himself, and yet identifiable as him: ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom is pretty much what Updike would have become if he’d had no connection to literature. Couples is so absorbing because Updike’s life had manufactured an immediate and traumatic mélange of moneyed adultery for its subject. The stories, too, are frequently so fine because of the immediacy of revelation: their best subjects — adultery, children and small-town bourgeois manners — were entirely familiar to Updike, and his linguistic inventiveness had something to work on.

Updike aficionados (like myself) may have their favourite novels apart from those acknowledged classics, but they are probably all different. I love Roger’s Version for its gleefully ruinous energy, and Memories of the Ford Administration — that gloriously boring title concealing one of Updike’s most entertaining books. On the other hand, In the Beauty of the Lilies is a total disaster, and other late books seem to show fluency continuing to work with nothing very compelling driving it. A woman blows some bubble-gum, and the prose rumbles on:

In this place, for decades a daily station of my pilgrimage, the young woman unthinkingly showed me her pink bubble, and then wolfed it back, seething with bacteria, into her oral cavity.

This biography moves very swiftly through the last 30 years of Updike’s creative life — he died, aged 76, in 2009 — and I think few people will complain about that.

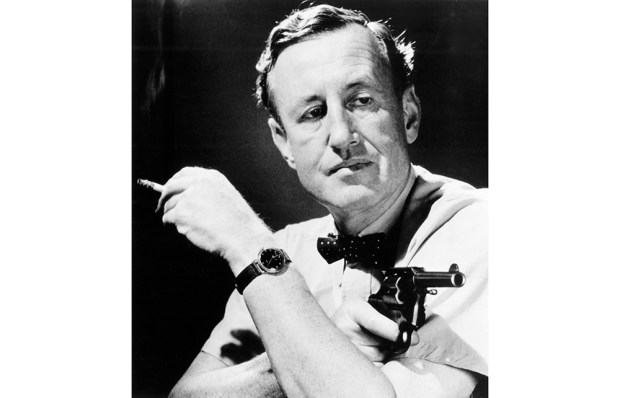

What went wrong, and what went right in the first place, are interesting questions. Updike’s elaborately Brahmin prose is so well-established that it comes as a mild surprise to discover how ordinary his background was. He was a small-town boy, the cherished only son (of course) of a schoolmaster and a would-be writer. He was a brilliant student, and was transformed into a star by his own clubbable nature, the Harvard Lampoon and a year at Oxford. He married before he graduated, and was being published by the New Yorker the second he returned from England. ‘He wasn’t despairing or thwarted or resentful; he wasn’t alienated or conflicted or drunk; he quarrelled with no one,’ according to Begley.

A period followed when he wrote apparently dazzling but beyond-parody New Yorker pieces. One, I am sorry to say, explains ‘how to make one’s way from the Empire State Building to the Rockefeller Center without ever setting foot on either Fifth or Sixth Avenue’, and is cringingly described by Begley as ‘delightful’. But soon Updike decided, rightly, that Manhattan was not for him, and he decamped with his family to a series of steadily larger houses and amazing feats of promiscuity in some charming New England villages. The novels that began to flow were deservedly acclaimed and immensely successful.

Begley thanks Updike’s first wife in the acknowledgements but does not mention the second. If this biography has a thesis it is that the adultery and the difficulties that characterised Updike’s marriage to Mary Pennington were good for him as a writer. His subsequent marriage, to Martha Bernhard, the most determined of his mistresses, secured him in an immense mansion, but the children had to make an appointment to visit and he was forbidden to write about the details of their life. (The uncharitable portrait of the wife in Toward the End of Time is the only good thing in that tiresome novel.)

The books kept on flowing — a historical novel, a magic-realist Tristan and Isolde set in Brazil, a future dystopic, and so on, as Updike amused himself more than his readers. The urgency, the ferocious need to transcribe what was there, whatever the affront to decorum, had gone, to be replaced by an apparently overriding preoccupation with his image. The slide began with The Witches of Eastwick, a book openly concerned to present the author, contrary to the views of feminist critics, as a great admirer of women. It sycophantically begins: ‘This air of Eastwick empowered women,’ and one’s heart sinks.

Begley’s biography is, on the whole, a solid one. Interestingly, he puts some stress on Updike as a religious writer, without seeing what a total waste of time religious investigation is to that most worldly of professions, the writing of fiction. And he occasionally misses the tone: the female character in a 1960s novel reading Alberto Moravia is not signalling a devotee of ‘highbrow Italian literature’ but rather a sexy sophisticate.

This may be the first biography, too, that describes the grand house in Nash’s Cumberland Terrace that Updike once rented as ‘snazzy’. It is disappointingly discreet not just about Updike’s 1960s’ adulteries but also, oddly, about the identity of his elder daughter’s long-dead first husband. I would have welcomed more on the immense — even comic — spread of Updike’s reputation: Nicholson Baker’s U and I is hardly mentioned, and Begley would never deign to tell us that Updike once hit the dizzy heights of appearing as a guest star in The Simpsons.

The acclaim, of course, stopped short of the Swedish Academy, which made rather a point (according to American critics) of not giving Updike his due with the Nobel prize. There are many great novelists who are not rated for their entire oeuvre. As Begley comes close to admitting, in the end Updike’s reputation will rest on the Rabbit novels, a body of sleek short stories and three or four other novels, including Couples. And that’s probably good enough to draw him out from the giant shadow of his master, John Cheever.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in