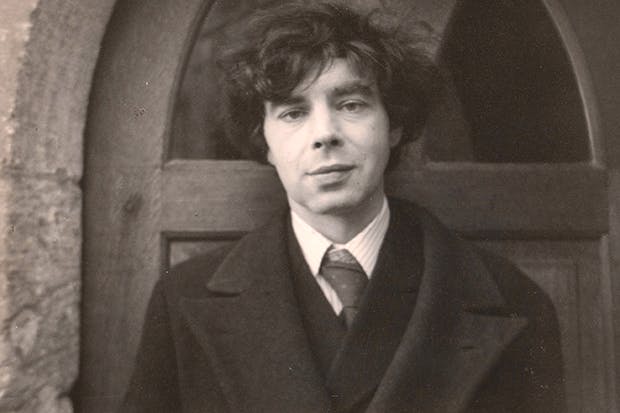

Who the hell was Dylan Thomas? Boozer, womaniser, sponger, charlatan — or master craftsman, besotted husband, generosity personified and one of the greatest literary talents of the 20th century? Or all of these? Fifty years ago (in November 1964) the writer Constantine Fitzgibbon grappled with these questions in The Spectator as he completed the first full-length biography of his friend the poet.

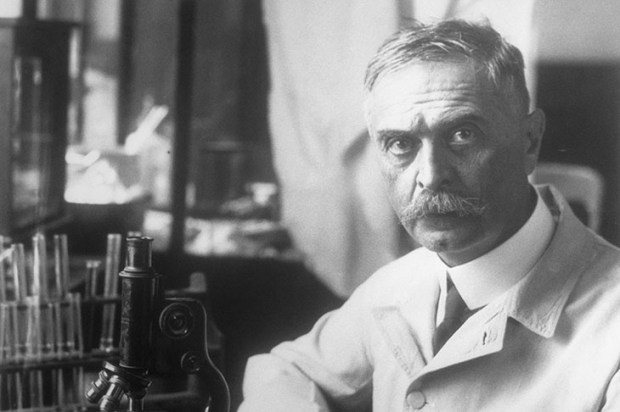

The article was illustrated by my late father, the artist Alfred Janes, a mutual friend (Thomas had a lot of them). It was one of three portraits that he made of his contemporary, whom he had first met in their ‘ugly, lovely’ hometown of Swansea in the1930s. This one was posthumous: Thomas had died in New York in 1953 aged 39.

‘It should be possible to form a rational judgment of the man and his work,’ Fitzgibbon wrote in his piece. ‘In literary and biographical terms, I hope this is the case, but any such assessment must now be performed beneath the shadow of the Dylan Thomas legend, or legends, and these are only incidentally concerned with literature or with truth.’

The self-styled ‘Rimbaud of Cwmdonkin Drive’ always provoked extreme reactions. Now, in his centenary year, the tussle over Thomas continues, and I am contributing with my own book, based on the three portraits by my father, painted over the course of their 20-year friendship. I grew up loving ‘Fern Hill’ and Under Milk Wood, which pleasingly echoed my own childhood surroundings in Gower and Swansea. I was born too late to enjoy the visits my family made to the Boat House in Laugharne, where Thomas settled after the war above ‘the mussel pooled and the heron / Priested shore,’ but I suspect I would have enjoyed them as much as my parents did.

The last visit was made just days before Thomas left for a fourth sell-out tour of America. They had turned the poet into a performer whose reputation was beyond even his wildest dreams. It caught up with him when, his health undermined by booze, fags, a terrible diet and inappropriately administered morphine, he collapsed and died in New York.

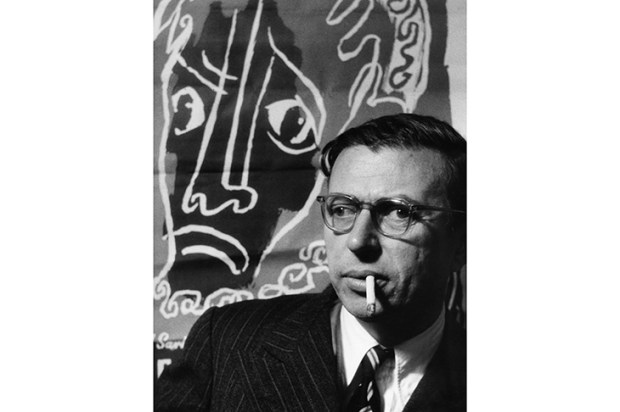

There was not a little rage at the dying of the light from those who pointed a finger at his American hosts. It prompted John Malcolm Brinnin, Thomas’s fixer-cum-manager in the US, to publish his own version of events, Dylan Thomas in America, three years later, a warts and all account that really put the cat among the pigeons.

To others, Thomas’s demise was good riddance. Many a Welsh tongue wagged at the no-good boyo, especially the kind that went to chapel on Sundays. ‘Dylan Thomas, ach y fi,’ as one woman put it, savouring the Welsh expression for ‘yuck’. And English writers like Kingsley Amis shed no tears. A lecturer at Swansea university in the 1950s, he was part of the poet’s circle — later re-incarnated in his Booker-prizewinning The Old Devils. But he met ‘Thomas the rhymer’ only once, and was disappointed not to get the ‘pub performance’ that he expected.

Amis, another Spectator contributor, belonged in a different, postwar, pared-down literary camp and loathed the Welshman’s ‘vague beauty-in-pit-dirt, How Green Was My Valley aura of the fruit-trees out of the coal-hill,’ as he told readers in an August 1955 review of a posthumous collection, A Prospect of the Sea.

Whoever once said that Thomas was too Welsh for the English and too English for the Welsh was probably right.It may have taken decades for his homeland to wake up to one of their greatest cultural assets, but now he is gripped in a warm Welsh embrace in the shape of Dylan Thomas 100 (www.dylanthomas100.org), a year-long programme of events backed with £1million of government money, not just in Swansea and Laugharne, but around the world. A congregation of Wales’s finest, including Michael Sheen, Jonathan Pryce, Tom Jones, Charlotte Church and Katherine Jenkins, are singing the poet’s praises. Griff Rhys Jones is even organising his own festival, Dylan Thomas in Fitzrovia, in October. The BBC, for whom Thomas made 200 broadcasts, is also creating a lot of noise with a dedicated season and microsite. A driving force behind the centenary is Hannah Ellis, the poet’s granddaughter. A primary school teacher, she wants to introduce his work to new, younger audiences and focus, understandably, on his achievements, rather than his failings. The shadow of the Dylan Thomas legend is a long one, and she has grown up under it.

Will we be any the wiser about who her grandfather really was? I’ll give the last word to my father, who wrote of Thomas after he died:

His empathy with the world and those around him was complete and he responded to his surroundings in such a way as sometimes to give the impression that he comprised multiple, diverse personalities — each one a stranger to the rest. He could be punctilious, outrageous, comic, tragic, or just totally unexceptional. The intelligentsia, the bartenders and even the herons could easily take him as one of themselves.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in