An eccentric English aristocrat who constructed a 20-mile network of underground corridors to avoid coming into contact with his fellow humans on his country estate; a Japanese dentist who has amassed an enormous collection of decorative details from buildings spanning a century, retrieved from Tokyo demolition sites; the German inventor of ‘Scalology’, who has spent 60 years studying staircases; and Inuit soapstone carvings of a Cold War early-warning station and of an airport terminal are among the surprises offered by the 14th Venice International Architecture Biennale.

The Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas is this year’s artistic director. With his team of researchers, he has not only composed a fascinating show — Elements of Architecture in the Central Pavilion at the Biennale Gardens — but by insisting on the announcement further in advance than usual of the theme to be tackled by the national pavilions (Absorbing Modernity: 1914–2014) he has also shaped a more co-ordinated overall view of the chosen subject than ever before. The theme has given rise to a variety of thought-provoking reflections on both Architectural Modernism and its impact on those who have lived with the results.

The Architecture Biennale was launched in 1980 and, since 2000, has expanded rapidly and fruitfully, alternating regularly with the Venice Art Biennale. There are 65 national pavilions this year, with ten countries — Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, United Arab Emirates, Indonesia, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Morocco, Mozambique, New Zealand and Turkey — participating for the first time, 22 official collateral events and scores of other fringe displays. For the first time it will have the same duration as the Art Biennale, continuing until 13 November.

Elements of Architecture has developed out of a two-year research programme, involving a host of experts from academia and industry, at the Harvard School of Design. This back-to-basics display and commentary is historical, contemporary and sometimes futuristic in its examination of the primary components of building: ceiling, window, corridor, floor, balcony, fireplace, façade, roof, door, wall, stair, ramp, toilet, escalator and elevator.

The oldest exhibit here is in the ‘fireplace’ section, a detached piece of a Neanderthal cave floor, from Spain, dating back 228,000 years, and among the newest are an ‘intelligent’ toilet that can measure glucose and hormone levels in urine (useful for diabetics and for women trying to conceive, respectively) and prototypes of elevators that travel not only up and down but also sideways.

The ‘door’ section takes us through a series of Italian Renaissance, Indian and Chinese monumental outer portals to the modern airport security gate. ‘Balcony’ offers an abundance of data both on the design of this feature and on its political significance as haranguing platform. In terms of sheer Olympian height, the Pope’s balcony overlooking St Peter’s comes out way on top.

One overall message that emerges from the show is that the most unlikely architectural elements are being digitalised, from those data-gathering loos to intelligent floors that can assist the disabled and overhead infrared heating systems that warm not the room but the targeted individual, with the temperature regulated according to personal preference, so that ‘man no longer seeks heat — heat seeks the man’.

In 1914 Le Corbusier came up with a classic piece of basic design, the Maison Dom-ino, so-called because these simple housing units were conceived as suitable for constructing in continuous terraces and/or at right angles to each other. The material for the frame was to be prefabricated reinforced concrete, which could be assembled by non-professionals and be furnished with walls and other components from local sources. These units were envisaged as a solution to the inevitable housing shortage that would follow the destruction of the war, but none was ever built.

A hundred years on, a group from Architectural Association in London, led by project architect Valentin Bontjes van Beek, has finally given physical form to the Dom-ino house, working from Le Corbusier’s sketches and substituting for concrete machined wood, which has turned out to be lighter, stronger and a more practical material for the design. Produced by a specialist Swiss timber engineering firm, the Dom-ino was delivered to Venice in kit form and assembled by the AA team in five days on a small lawn in front of the Central Pavilion. It will later travel on to Bedford Square in London and to Japan.

La Corbusier later became a promoter of mass housing on a grander scale of the kind that Modernist architects came to adore but that many of the residents who had to live in these complexes often deplored. The French Pavilion’s exhibition Modernity: Promise or Menace, curated by Jean-Louis Cohen, examines a nightmare conclusion to a modernist dream.

France was in the forefront of using prefabricated concrete systems for public housing and a development at Drancy in 1934 included five 14-storey towers, the region’s ‘first skyscrapers’. But the remote location proved unpopular and the estate became a police barracks. From 1940 it was used as a concentration camp from which more than 60,000 French Jews were deported to Nazi death camps, as Le Corbusier’s domestic ‘machine for living’ became a horrifying component of a production line for killing.

A radical change of mood is supplied by an installation devoted to Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle, the 1958 comic send-up of the Modernist architect-designed house, in which tout communique (everything connects). Here, a 1:10 scale model of the Villa Arpel, designed by Tati’s painter friend Jacques Lagrange for the movie, is accompanied by clips of our pipe-smoking hero battling with the building and its modern conveniences.

The presence of two concrete cows, transported from Milton Keynes, at the foot of the steps to the British Pavilion and the blobby, nice friendly mandarin-orange graphics adorning the interior walls set the tone for A Clockwork Jerusalem.

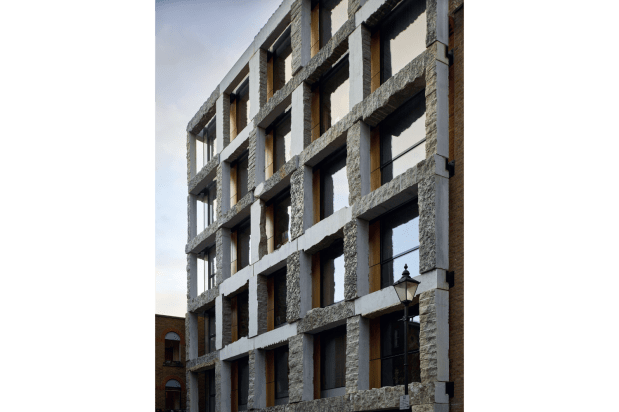

Curated by Sam Jacob and Wouter Vanstiphout, this entertaining tour of architectural utopianism à l’anglais argues that even British architects perceived as heartless Brutalists were secretly in the nostalgic grip of Ruins, Romanticism and the Picturesque. This the curators illustrate with examples such as the neo-Georgian crescents at the Hulme Council Estate in Manchester (now demolished), the rusticated concrete of the Barbican Centre and the plans to make Milton Keynes a ‘Forest City’ by entirely concealing it behind tall trees.

The top-down imposition of building norms is a reality that is being increasingly questioned around the world, with demands that the end users should play a greater role in the planning process. A particularly striking, indeed encouraging, case of this rethinking is provided by Arctic Adaptations: Nunavut at 15, in the Canadian Pavilion, curated by Lola Sheppard, Matthew Spremulli and Mason White, with architectural models carved in soapstone by local Inuit artists providing some of the illustrations.

Nomadic for thousands of years, in recent times the Inuit of Canada’s Arctic regions were effectively forced into settlements and into imported types of buildings quite alien to native traditions — the average modern kitchen is not configured to deal with a freshly caught seal, for example. In 1999, Nunavut (literally ‘our land’) separated from the Northwest Territories to become the country’s newest and, at two million square kilometres, largest territory.

Arctic Adaptations presents a series of new projects for housing and health, education and recreational facilities designed by combined teams of Canadian architects and Inuit organisations. And from the evidence here, these promise to be both imaginative post-modernist architectural designs in themselves and a model for community building elsewhere.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in