‘Curious to see Mrs Aveling addressing the enormous crowd, curious to see the eyes of the women fixed upon her as she spoke of the miseries of the dockers’ homes, pleasant to see her point her black-gloved finger at the oppression, and pleasant to hear the hearty cheer with which her speech was given.’ So Labour MP Robert Cunninghame Graham described Karl Marx’s youngest daughter, Eleanor, giving a speech to 100,000 demonstrators in Hyde Park at the height of the 1889 dock strike. ‘Brilliant, devoted and beautiful,’ agreed the trade union leader Ben Tillett. ‘During our great strike she worked unceasingly — a vivid and vital personality, with great force of character, courage and ability.’

And in Rachel Holmes’s bold, fluent, scholarly and rewarding new biography, Eleanor Marx’s voice as polemicist, activist, feminist and socialist is rediscovered. It does not quite match the heights of Yvonne Kapp’s masterful 1970s two-volume biography of ‘Tussy’ (as she was known in the nickname-rich Marx-Engels environs), but nonetheless covers familiar territory in a refreshing manner and has made good use of the archives to craft a sophisticated account of Tussy’s thwarted life and socialist legacy.

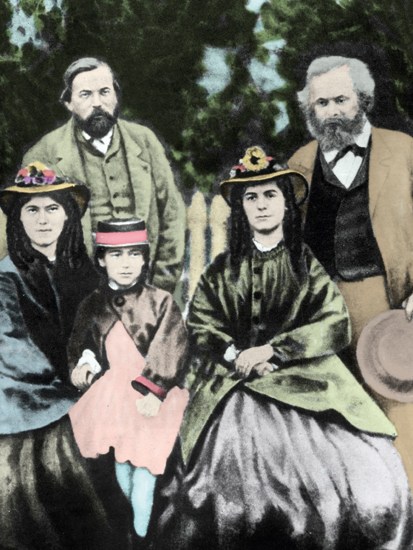

Whatever did Marx do to his daughters? The careers and families which Eleanor, Jenny and Laura built seemed never to match the impact of their father’s love for them:

My earliest recollection is when I was about three years old and Mohr [Marx] was carrying me on his shoulders round our small garden in Grafton Terrace, and putting convolvulus flowers in my brown curls.

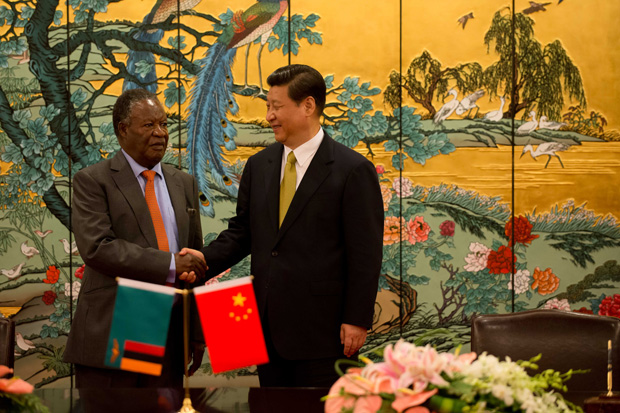

With a sometimes over-generous literary flair, Holmes deftly describes Eleanor’s upbringing in the chaotic, erratic, but mostly joyous Marx household. The picnics on Hampstead Heath, the Shakespeare and Goethe, the ever-present Uncle Engels. One unexpected insight is just how interested Marx and Engels were in matters Chinese during the 1860s — which coincided with Tussy enduring a bout of jaundice:

I remember well, that seeing myself quite yellow I declared I had become a Chinaman and insisted on my curls being made into a little pigtail.

At the same time, Tussy was always adamant that she would not be the third daughter left behind in the household to look after Mohr. She was an agitator and activist in her own right. Denied much formal schooling, she learned her political philosophy from Engels, the British Library Reading Room, and the ever-shifting array of exiled European socialists who made their way through the Marx living room.

Holmes’s biography emphasises Tussy’s role both as the earliest biographer of Karl Marx (and, hence, the initial codifier of his thinking) and as a significant British socialist in her own right. Holmes seems to lose interest in her first task but more than makes up for such omissions with her account of Tussy’s journey toward the political front line.

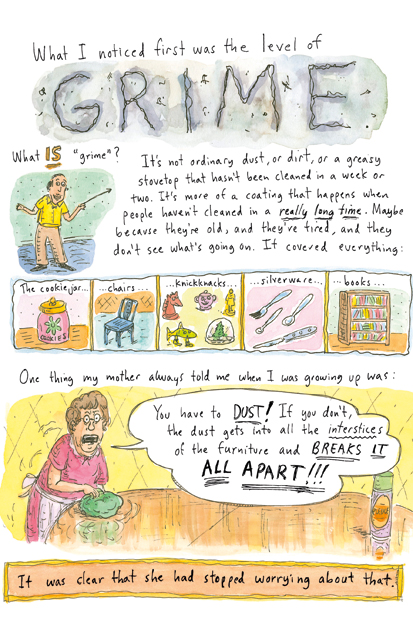

Because far more than either Marx or Engels, Tussy believed in praxis — in the practical application of her socialist values. She began by drawing on her love of drama to teach students sitting the Cambridge Higher Local Examinations instruction in As You Like It. She then branched out into night classes for the Social Democratic Federation. ‘A score of memoirs by working-class leaders bear testimony to Eleanor,’ writes Holmes, ‘who tutored them in reading, writing, accountancy, and political and economic theory, as well as speech-writing and public speaking.’ And, quite rightly, Tussy thought that ‘education to a socialist means also art education’.

As a socialist agitator and polemicist in late-19th-century London, Tussy was inevitably drawn into the politics of the East End. ‘To go to the docks is enough to drive one mad. The men fight and push and hustle like beasts — not men — and all to earn at best 3d or 4d an hour!’ She visited the homes of the poor, organised union committees, campaigned for an eight-hour day and better pay. Her skills were swiftly made use of by the gasworkers’ and miners’ unions as well as the splintering constellation of international socialist bodies. Just as her father had taught her, she translated motions, chaired committees and penned pamphlets.

Tussy’s most significant intellectual contribution was in the field of feminism. She deepened the work of August Bebel and Engels on the materialist foundations of sexism with her own readings of Darwinian history and, more importantly, the insights she had drawn from her close readings of Ibsen and Flaubert. Yet while she agreed with the traditional Marxist line that female oppression was the product of economic factors, she also supported the campaign for equal suffrage, explaining:

Truly the working woman approves the demand of the middle-class women’s movement. But only as means to the end that she may be fully armed for entering into the working-class struggle along with the man of her class.

All of which makes the defining tragedy of Tussy’s life — her relationship with the dreaded Edward Aveling — the more darkly compelling. ‘Aveling was one of those men, who have an attraction for women quite inexplicable to the male sex,’ thought Henry Hyndman; ‘ugly and repulsive to some extent, as he looked, he needed but half an hour’s start of the handsomest man in London.’ He was a shit of the highest order — jealous, petty, vain, insecure, greedy, devious, sadistic — but Tussy loved him. ‘Well then this is it — I am going to live with Edward Aveling as his wife,’ she announced to friends in 1883. ‘You know he is married, and that I cannot be his wife legally, but it will be a true marriage to me.’ It certainly wasn’t to Aveling, and Holmes charts with wretched precision the catalogue of abuse meted out to Tussy — who in her own personal life could never live up to the empowering feminism she had done so much to promote.

Tussy’s early years were overshadowed by Mohr; her end was at the hands of Aveling. Her life has so often been depicted as a traumatic experience caught between Marx and this monster. The great success of Holmes’s book is to understand the richness of Eleanor Marx’s contribution on her own terms.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in