The civilised world felt as if its heart had been touched by an icicle. Photographs of murdered children. Biogs of people like us; we could have been on that plane. We will be on similar ones, now reminded of our vulnerability to frivolous barbarians in possession of terrifying weapons. Grief and fear lead rapidly to anger: to the demand that something must be done to punish the evildoers and rescue us from insecurity. That might seem a comforting thought. It is also false comfort, for there is a basic problem. What can we do?

When in doubt, think hard, in a long historical perspective. Paradoxically, that apparently arid discipline may bring real comfort.

The disintegration of empires always makes the earth tremble as it is battered by tumbling geopolitical masonry. Think how long Europe took to regain the civilised standards it lost with the fall of Rome. Consider the Austro-Hungarian and Turkish empires: above all, the British one. Our imperial exhaustion led us to abandon Palestine and Pakistan, those two Ps which no princess’s mattress can suppress: those two possible catalysts for a nuclear war which could destroy mankind.

By comparison, the end of the Russian empire has been surprisingly pacific. No insoluble problems have emerged, and no strategic quarrel with the West. There are diplomatic difficulties, but if we cannot resolve them without threats, posturing and insecurity, we will be guilty of contemptible ineptitude. We must start by considering different versions of history. The Russians believe that they broke Hitler after appalling sufferings and sacrifices, none of which were fully aided by or appreciated in the West. They also believe that they renounced their empire, virtually accepting their defeat in the Cold War — while the West promptly set out to continue that war by extending the frontiers of Nato in order to humiliate Russia.

It is a partial view, omitting interesting details such as the Molotov/Ribbentrop Pact and the nature of empires. The western empires in the third world had a civilising mission. This was not true of the Soviet one in central Europe. That said, the Russian version of recent history is no more dishonest than de Gaulle’s account of the liberation of France in 1944. Since 1945, French foreign policy has owed more to post-traumatic stress disorder than to a rational appraisal of events. The French had an excuse.

Look at the American South. Defeats inflict psychic punishment which endures for decades. In its response to Cold War victory, the West had no such excuse. Our handling of Russia since 1990 has been a succession of abject failures.

We needed an aphorism, and a conclusion. The aphorism was Churchill’s: in victory, magnanimity. The conclusion was more complex. Russia was on a new trajectory. Where it would lead, no one knew, least of all the Russians. It might therefore seem sensible to scrap our concepts and retain our weapons systems. A succession of western statesmen should have gone to Moscow to praise holy Russia, eternal Russia, heroic Russia: to give thanks for the cultural and spiritual reunion of Europe. The vast moral and artistic resources of the Russian people were once again part of the common heritage of mankind. Let the glory of renewed Russia shine forth as a light unto the nations.

The next day, when everyone was sober, there should have been an entirely different tone of discussion, owing much more to arm-wrestling than to apotheosis. The Westerners should have made it clear that although Nato would continue to exist, we were in the market for a new treaty that offered collective security to western Europe and to the former Soviet Union. This military entente could be reinforced by trade arrangements offering evolving co-operation with the EU.

All that might have worked under early Putin. We could have done business with him. His supposed greatest liability, the KGB past, should have been an asset. KGB officers had one advantage denied to ordinary Russians: information. A KGB operative in the West, tasked with extolling the Soviet system, must have felt like a member of the flat-earth society who had booked a round-the-world cruise.

From the outset, Mr Putin was never an attractive human being. But he was a Russian patriot — nothing wrong with that — who wanted things to work: better than the alternative. He knew that the old Soviet system had not worked and had heard talk of free markets and democracy, which gave better results. That is when we ought to have been encouraging him.

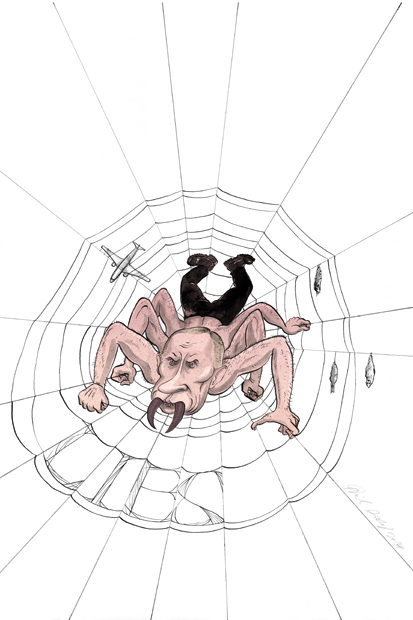

We were too slow, and he was always a ditherer, easily alarmed by the threat of chaos. He was also seduced, by power, populism and plunder. The worst aspects of his character have now taken command.

So how should we respond? Cautiously. When the plane was shot down, there was a certain amount of anxious chatter about an Archduke moment. But we are not going to start the third world war in eastern Ukraine. There is a lot of talk about sanctions. There is even the fantasy that if the oligarchs were hit, so that their wives could no longer shop in Harrods, they would turn on Putin, in the way that the German generals might have turned on Hitler. Forget it; this is no longer the Rhineland. This is more like the Anschluss. Putin is impregnably popular.

That has one positive point. As he has nothing to fear from democracy, he has no reason to suppress it. Russia’s crablike moves towards modernisation and progress could survive Putin. As for sanctions, they have a long history of futility. In Russia, they might succeed in degrading the economy, so that it remained wholly dependent on natural resources. That is in no one’s interests. Russia has enough natural resources to pay a lot of bills and wages while deteriorating into truculence. The alternative is an increasingly sophisticated Russia, which could enhance both domestic stability and world GDP. Sanctions encourage backwardness. Russia is already backward enough.

Can we do anything at all? Yes. Consider Bismarck, the greatest of foreign ministers. What would he have done? Called a congress. Let us say the Congress of Prague, to convene in the early new year. That would give everyone the excuse to calm down and give their rhetoric a cold shower. It might also free attention to the real threat facing the world. The Ukraine is a sideshow. Gaza is worrying.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in