Could you ever torture someone? Could you, under different circumstances, in a different world (I hope) than the one which led you to this Spectator, be as brutal as the fighters of the Islamic State? Your answer, I reckon, is most likely to be no. Most people these days talk of IS jihadis as if they’re unnaturally evil, an aberration — and you can see why. If the IS are uniquely bad, it means we don’t have to re-evaluate the species, and to boot, it gives us licence to stamp them out.

It is tempting to think of them as an anomaly, but on this point I’m with Toby Young, who earlier this month wrote that the Catholic notion of original sin explains brutality best. The seeds of cruelty are in all of us — not just IS, or young men, but girls and grandparents too. We could all, if we chose, grow into terrible monsters. Nothing human is alien to me and all that, which is sometimes used as if it were an excuse these days, but is not.

What we forget about IS, I think, is that the boys who herd off to join the jihad in Iraq or Syria don’t usually start off as monsters — they are made into them along the way. There are techniques for making sadists out of young men that have been practised by militias worldwide and throughout history. In fact all that throat-cutting and torture, which seems so particularly diabolical for being unnecessary, is actually a crucial part of the monster-making process itself.

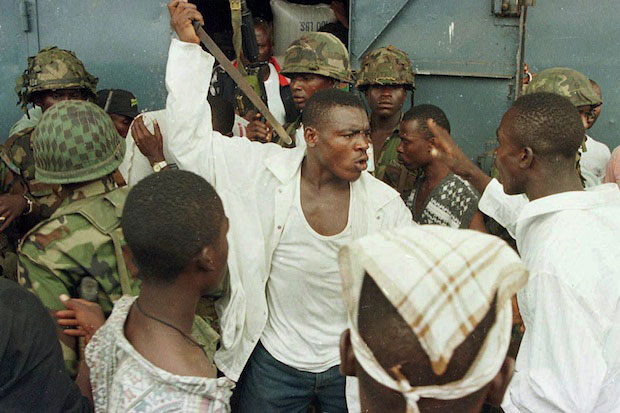

I heard all about it once from an expert, a man by the name of Joshua Milton Blahyi (General Butt-Naked to his foes), who was once a warlord in the Liberian civil war. Back in the bad old days, Joshua specialised in turning boys into psychopaths, and though his recruits were often younger than your average jihadi (12 to 18, say) there’s no hard line between boyhood and manhood, and the method was anyway much the same for twenty-somethings, he said.

I was introduced to Joshua in 2008 by a daredevil older cousin, and interviewed him on his breeze-block porch on a hill outside Liberia’s capital, Monrovia. It was the rainy season, and the monsoon tore down behind him. I remember Joshua’s huge head, beaded with sweat.

He began, he said, by promising boys status. ‘They followed me at first because I was powerful and strong, and they wanted to be important like me.’ It was crucial that this first step was freely taken; that it was their choice. After that, the monster-making began. They were shown violent movies. ‘So they can see,’ said Joshua, ‘that these people in the movies, they intentionally shoot people that die, that killing is just a Hollywood game.’ Hollywood movies, I asked, not African ones? ‘Yes, Hollywood films.’

The next step was to let them play with guns, shooting blanks, showing off, pretending to kill, and then: ‘We give them a knife to stab dead bodies,’ said Joshua. ‘At first it is hard for them, they feel fear. Later they are stabbing the bodies on and on… On and on and on.’

Of all weird and horrifying elements of our conversation, that’s the bit I liked least: ‘On and on and on.’ It’s as if, in the act of stabbing corpses, a switch flipped that suddenly undid the boys’ humanity. Joshua agreed: ‘After that they are wicked. They are happy to kill.’

For the purposes of understanding — not in any way excusing — the IS, it’s interesting that Joshua said that the leader of an army of man-made monsters can never rest. You must escalate the violence all the time, he said, so as to keep the boys in line. Once they’re happy killing, you make them rape, torture, behead. There are things Joshua made his young recruits do that are too horrible and too sad to repeat, but they served this triple purpose: to inure young men to compassion; to keep them frightened of and obedient to their commander and to scare the bejeezes out of the opposition. ‘If our enemies think we are crazy, so we win before we even fight.’

Does it help to understand that all this horror beamed back from the IS isn’t actually gratuitous; that if you’re out to win an asymmetric war it serves a purpose? I think it does. It should, if we’d any nous, help us understand how to combat the IS too. Islamist commanders dependent on diabolical reputations should be laughed at, not treated as bogeymen. One further useful point: in Joshua’s experience, man-made monsters can be re-humanised, though his method may be, for some, more distasteful even than the original brainwashing.

Joshua gave up his career as a psychopath warlord after a visit from a local Christian preacher. He had sacrificed a baby to the hungry tribal spirits who ensured his safety in battle, and was preparing for just another skirmish, when this preacher braved the rebels’ den to beg him to repent. Perhaps Joshua was already beginning to sicken of blood, because for some reason he didn’t kill the man, but listened. Then he disbanded his army and is today a preacher himself.

There are many who are cynical about Joshua’s conversion, and it’s true, epiphanies are all the rage among former warlords in Africa, especially those with an eye on politics. But I saw the shadows shift behind Joshua’s eyes; the uncalculating chaos in his mind. He’s a man driven almost mad by what he’s done, and I chose and choose to believe him.

There’s at least a partial proof in his new mission too. For the last few years Joshua’s been seeking out the boys he once turned into killers, converting and rehabilitating them. First he weans them from amphetamines, then he helps them confront that fateful choice they made. After that, if they are to remain in Joshua’s church, they must visit their families and ask for forgiveness. It’s interesting to me, a Catholic, that just as original sin best explains our propensity for cruelty, so the recovery from sin requires repentance, confession, mercy, absolution.

Some say that Christianity is just a useful crutch for recovering psychopaths in Liberia, because west Africans will always believe in spirits. Joshua and his boys will swap their murderous old demons for a benign Christian God, but never for the lonely void of atheism.

In which case, remember that the brutalised boys of the IS are inherently spiritual too. They have believed in and followed a god who demands murder and offers glory. If and when they ever come back, perhaps, like Joshua’s boys, they might be best served by one who offers forgiveness.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in