Listen

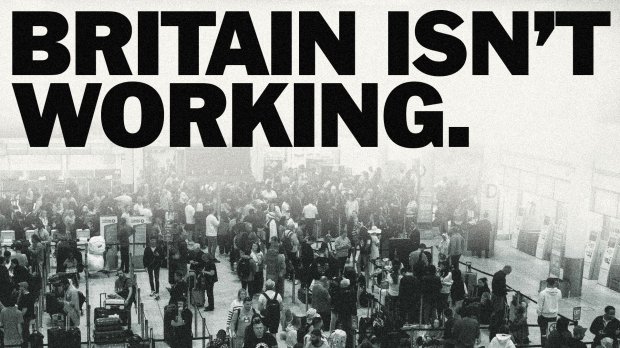

Next week, the most important vote in recent British history will be held. Indeed, it may well turn out to be one of the last ballots in British history. Seven months ago, this magazine devoted its front page to warning that the United Kingdom was at grave risk of dissolution. The unionist apparatus had decayed, argued Alex Massie, and Alex Salmond was the best late-stage campaigner in Europe. The SNP deployed the language of nationhood and destiny, while the ‘no’ campaign droned on about the Barnett Formula. The conditions for calamity were in place.

At last, the Prime Minister has realised the seriousness of the threat: a ‘yes’ vote would end his political career, but that would be the least of it. The United Kingdom, the greatest union of countries that the world has known, would be dissolved — and for the worst of reasons. There is a pitifully thin logical case for separation: devolution has so far done little for Scotland’s public services, so more powers are unlikely to bring more help. But this debate has come down to something else: the SNP has been able to articulate the emotional case for a separate country. Britain’s politicians don’t seem to be able to make the case for Britain.

The British public have no such inhibitions — if The Spectator’s postbag is anything to go by. Almost everyone who responded to our request for readers to write in with reasons for Scots to stay has made the argument that so many unionist politicians seem unable to comprehend: that the importance of Britain is about identity, belonging and nationhood. It’s about a shared history and shared prospects, of tolerance and being tolerated. When we talk about Britain, we talk about a set of values jointly created by the Scots, Welsh and Northern Irish.

One reader, the son of an immigrant, writes that his life in Britain in the 1970s was made better by knowing that Britain was a country of differences and compromise, rather than one which was seen as the homeland of a single tribe. Another, from west London, talks about how important it is to her that when she steps off the train at Aviemore she still feels at home. You can hear the Scottish nationalists scoffing: who would prevent her visiting a separate Scotland? No one, of course, but it would not feel like home. Something very precious will be lost — and that loss would diminish us all.

Politics is not only about narrow self-interest. There are a good number of Scots who would vote for independence (or the union) even if they were convinced they’d be worse off as a result. Such voters are insulted by attempted bribes. To George Osborne’s eternal shame, his Treasury officials even published a document telling Scots that voting ‘no’ would allow them to ‘share a meal of fish and chips with your family every day for around ten weeks, with a couple of portions of mushy peas thrown in.’ Is it any wonder that so many Scots think ‘to hell with the lot of you’?

This explains the upsurge for independence: we see exasperation with a political class that seems intent on demonstrating its incompetence. Scrambled offers of more devolution are being made so late as to be incredible. Making threats is not the same as changing minds. For years, Scottish Labour has been used to winning without really fighting, hoovering up ‘safe seats’ after telling scare stories about Tory government. This has led to a decay in the basic political apparatus which is (alas) on full display now. Most SNP activists, by contrast, have spent all their adult lives preparing for this one vote.

The Prime Minister should not need speech-writers to extol the merits of Britain. He can just consider our history: in 1707 England was a hive of religious intolerance while impoverished Scotland was beset with feudal warfare. Within decades Great Britain had become the first industrial nation and led the world in scientific discovery. You can’t read about Britain’s history without coming across those who, like Robert Owen, the Welsh mill owner and early socialist, achieved great things by going north of the border to Lanarkshire, as well as others who, like the engineer Thomas Telford of Dumfriesshire, came south to work.

None of our readers’ letters dispute that Scotland could be independent — indeed, one even posits that Kent could separate. But why engage in the politics of grudge, gripe and separation? Change the word ‘Scotland’ to ‘England’ in the SNP’s slogans and you have the unattractive creed of English nationalism. How people would wince at a movement which proclaimed ‘England’s Future in England’s hands’? It would be accused of xenophobia, and of wanting to retreat into a little world of its own.

There is still time to save the union, but it requires more passion than the ‘no’ camp has so far shown. Twice, David Cameron has saved his political career by making impressive speeches at crucial moments. He needs to do so again, and this time the stakes are far higher. If the Prime Minister and his allies are still trying to find the right words, they need look no further than these pages.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in