As I think I said in this column the other week, I used to sneak into English lectures at University College London, while officially studying at the School of Oriental and African Studies round the corner. I attended these lectures with such keenness and regularity that an English student called John Bradley, who now writes sometimes on Middle Eastern politics for this paper, one day asked me to contribute to the London Review — a UCL student literary magazine. I chose to review a handbook of ferret husbandry by the artisan hunter D. Brian Plummer, who was my favourite writer at the time. I’d never written anything other than school or college essays before, let alone had anything printed. A few weeks later, there was my ferret husbandry review between glossy covers among erudite and witty contributions about Henry James and Ronald Firbank. I was thrilled and embarrassed in equal measure.

A few days later, John Bradley said to me that one of the UCL professors had liked my contribution and wanted to meet me. It was a professor with an honorary chair — the Lord Northcliffe Chair of Modern English Literature — whom I had neither met nor heard lecture so far. ‘Don’t be intimidated by his dour Scot persona,’ he advised me. ‘He’s actually quite funny.’ So John Bradley arranged a time and together we went to see this professor of his. He was in his study, which was huge and bare and totally devoid of books, except one paperback novel that the professor was reading on his lap with great absorption. As we walked in, he held the book aloft triumphantly like a trophy of war. ‘Yes!’ he hissed, through defiant, gritted teeth.

I was introduced. The professor said he’d enjoyed my ferrets piece, the best thing he’d read for a long time, he said. Did I like football, he said? Who did I support? I told him, and we chatted about football. He was Spurs. Then he said I should write a book. He would put me in touch with his agent. All she needed from me was a chapter and a synopsis. Then we could tout it round the publishers and flog it. A book? What of, I said? Autobiography, he said. Then he wondered whether either of us had a second class stamp on us by any chance. It seemed to be a matter of urgency. As it happened, I had a book of them, which impressed and delighted him more than anything. This professor, whoever he was, struck me as humble yet defiant, deadpan yet alive, miserable yet humorous. A comedian. Above all, he seemed to repudiate utterly any deference owing to his position, whatever anyone might imagine that to be.

His agent was in touch promptly. Her name was Alexandra Pringle. Just a chapter and a synopsis, she said. That’s all. So I did that and sent it to her, and she sent it to some publishers, and then she took me around the same publishers so they could have a look at me. We went to Penguin, Granta, Fourth Estate and Hamish Hamilton. At the sight of Alexandra Pringle walking in, all the publishers and their minions would light up with pleasure, and they seemed very glad to see me too, and I had the impression that the professor had got me on the books of one of the top agents in London. Her office address was 9 Orme Court. Spike Milligan had rooms on the ground floor. As a child I addressed to there the only fan letter I ever wrote to Spike Milligan, and for years afterwards the address 9 Orme Court held a kind of magical significance for me. You could also smell Eric Sykes’s cigar smoke on the first-floor landing. Meanwhile I was still committing Swahili noun classes to memory and sneaking into English lectures at UCL.

Several publishers were interested in my book, so it was auctioned. Hamish Hamilton won it with a bid of £55,000. When I went to see the professor to tell him about my extraordinary bit of luck, he wasn’t at all surprised. Did I have another stamp on me, he said? I gave him a stamp. ‘James Boswell,’ he said. ‘Ever read Boswell?’ I admitted it: I hadn’t. ‘I love Boswell,’ he said. He said the word ‘love’ with such feeling I thought he was going to cry.

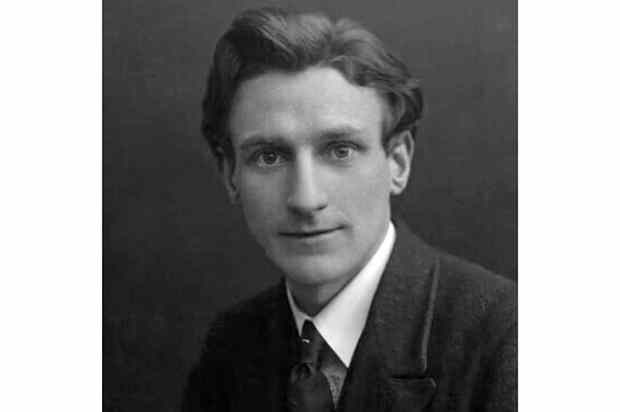

Karl Miller died last month aged 83. The obituaries said he was ‘the greatest literary editor’ of his time, and that he took on and championed many writers being published today. I’m so thick, I didn’t really know much about him until I read last week’s obituaries. He used to call me his ‘great white hope’. I failed him, of course. And I never kept in touch. But after reading those heartfelt and admiring obituaries last week, my pride at being one of Karl’s increased tenfold.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in