This dispatch comes to you from Venice — where I arrived at sunset on the Orient Express. More of that journey on another occasion, I hope. Suffice to say that if you happen to have been wrestling with the moral choice of bequeathing what’s left of your tax-bitten wealth to ungrateful offspring or spending it on yourself, don’t hesitate to invest in a last fling on this time capsule of elegant extravagance. Made up of rolling stock built in the late 1920s, the train itself symbolises everything that 20th-century Europe was good at — engineering, craftsmanship, style, cross-border connections — when not distracted by political folly and war. Views from the bar car of triple-dip-recession-hit industrial Milan and Bologna seem to symbolise much that Europe habitually gets wrong, starting and ending with economic management.

Or so I mused, with a negroni in my hand and the lounge pianist playing ‘As Time Goes By’ in my ear. And naturally I thought of my predecessor Christopher Fildes, who loves trains and negronis: older readers will recall with pleasure his ‘Negroni Index’, a measure of the true international value of the old Italian lira and the newly launched euro. The 3,000-lira negroni was his benchmark, and I see from our archives that he was still able, in 2001, to buy three of these excellent cocktails for the equivalent of less than £10. I have to report that this is one index which has soared inexorably through all the market turmoils of recent years: three today, on the train or in any Venetian hotel, will cost you £50 — or if you order them at the lovely Locanda Cipriani on the island of Torcello and travel there and back by fast water-taxi, more like £300.

That too may feel like money well spent before the taxman nabs it — but my real point is that Venice’s fantastic prices reflect its status as a honeypot mercantile city-state, whose ancient foundations are being eroded as much by the marching feet of mainland Chinese and fat American tourists as by the wash of giant cruise-ships. Outside my hotel is a fine equestrian statue of Victor Emmanuel II, first king of reunited 19th-century Italy, and I overhear a guide telling his puzzled Chinese flock, ‘Actually we don’t like him here because we’re Venetians, not Italians.’ It reminded me of another of Christopher’s wheezes: ‘Project Rubicon, my plan to bid for Italy and break it up, restoring such historic currencies as the Venetian ducat and the Papal scudo, is looking better by the moment,’ he wrote in his valedictory column in 2006. And better still today.

Boneheaded bonus cap

I’m as puritanical as anyone on the subject of bankers’ pay, but the EU bonus cap was a boneheaded idea in the first place and London’s wily financiers will go on finding ways to circumvent it, with the tacit support of the Bank of England, despite last week’s attempt by the European Banking Authority to get tough on the use of ‘role-based allowances’ to increase variable pay as a substitute for bigger bonuses.

The cap was promulgated by the European Parliament — British Lib Dem MEP Sharon Bowles to the fore — as an addendum to new rules on bank capital requirements. Its declared intention was to discourage a return to excessive risk-taking, but it was clearly also punishment for bankers’ collective lack of remorse after the financial crisis. A source in Brussels tells me the Commission there would like to have pushed the cap through itself, but thought it smarter to let MEPs be seen to be responsible for such a controversial measure.

Either way, the cap (limiting bonuses to 100 per cent of base salary unless shareholders approve up to 200 per cent) notionally came into effect in January but has been widely and gleefully abused by the use of ‘allowances’, often on top of higher base salaries. If there’s any real impact — bankers are keen we should know — it has been to increase risk rather than diminish it, by increasing fixed costs while accelerating hiring and firing, thus diminishing collective memory, reducing ability to respond to market shocks, and damaging morale. The only positive effect is that the cap may be pushing talented people out of the biggest (and often riskiest) investment banks towards smaller, partnership-based firms — which are actually a better business model for the City in all sorts of ways. But as so often in the financial world, that’s just another unintended consequence of bad regulation.

The Beeb’s disdain

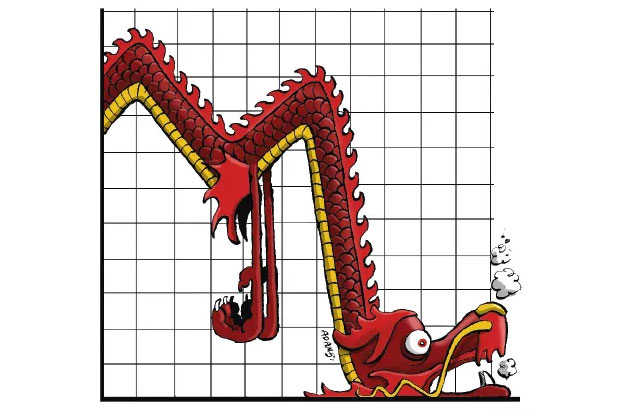

Last week’s market tremor, provoked by renewed fears of eurozone stagnation and a slowdown in global growth, was serious enough for IMF chief Christine Lagarde to feel the need to pronounce, in her most soothing tone, that it was ‘maybe at this stage an overreaction’. But if you were listening to the Today programme on Saturday morning, you might have thought it was all a bit of a joke — and one that served irresponsible investors right. In the absence of economics editor Robert Peston and his almost invisible successor as business editor, Kamal Ahmed, John Humphrys conducted a notably flippant interview with ‘one of the world’s most influential investors’, Jim Rogers — who in fact retired from Wall Street in 1980 to ride his motorbike, set up home in Singapore, punt his fortune in commodities and emerging Asia, and pour scorn on debt-addicted western governments and money-printing central banks. ‘A pox on all their houses,’ he once told The Spectator.

The amiable Rogers might admit he’s no expert on European economies and stock markets, since he doesn’t invest in them and is unlikely ever to do so. But for Today’s producers, one guru is as good as another in the great casino of greed. Humphrys didn’t seem to be listening to Rogers’s answers anyway, but was eager to ask whether everyone who has holdings ‘in the stock market or whatever’ should sell up and ‘stick the money under the bed or something?’ Mme Lagarde, if she was listening, must have been horrified. It was a classic example of BBC disdain for market capitalism.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in