Nancy Mitford would not call them ‘toilet books’, that’s for certain. Loo books? Lavatory books? One or two people I know favour ‘bog books’. And having written one or two books myself that teeter on the edge of frivolity, I know that for your book to be kept in what Americans call the ‘bathroom’ is essentially a compliment. As long as it’s there to be read, of course.

Oddly enough, the two best loo books of the year I have already and separately reviewed in these pages. The Most of Nora Ephron (Doubleday, £20, Spectator Bookshop, £16.50) is an immaculately chosen compilation of the late American humorist’s journalism, blogs, meditations and random riffs, topped off with an extract from her best-known screenplay When Harry Met Sally. (If you have come to her through her two recent books of essays, it overlaps only a little with them and so is still worth acquiring.)

Michael Frayn’s Matchbox Theatre (Faber, £12.99, Spectator Bookshop, £10.99) is the most highbrow humorous book of this or any other year, a collection of 30 brief, abstract sketches, designed to be performed in the most intimate theatre space of them all, your own head. It’s also very funny, a rare and beautiful thing in itself.

Here, then, are the best of the rest. 1,411 QI Facts to Knock You Sideways (Faber, £10.99, Spectator Bookshop, £9.89) is the third of these silly fact compilations in as many years, but maintains the high standards of inconsequentiality attained by the first two. There are 60 people in Venezuela whose first name is Hitler. Eating 20 million bananas would give you a fatal dose of radioactivity. Queen Victoria had jewellery made out of her children’s milk teeth.

As a dedicated trivia-hound myself, I will admit to having heard one or two of these before, but there’s always something extraordinary awaiting you on the following page. From 1934 to 1948, the motto of the BBC was Quaecunque, the Latin for ‘whatever’. Martian sunsets are blue. The International Space Station travels at five miles per second.

Don’t pretend that these snippets of information do not enhance your existence in a small way, because I won’t believe you. In some ways these books are the best of QI: pure information, with all the smugness filtered out. Well, most of it, anyway — without the tiny filaments of smugness holding it together, the show would crumble into dust.

John D. Barrow’s 100 Essential Things You Didn’t Know You Didn’t Know About Maths & the Arts (Bodley Head, £10, Spectator Bookshop, £9.50) rides the wave of popular maths books, which I sometimes suspect are more frequently bought and given as presents than actually opened and read. People love the idea of maths, but the ideas within maths they can find rather forbidding. Barrow, professor of mathematical sciences at Cambridge, is a prolific populariser in the manner of Ian Stewart: he asks interesting questions and then answers them in a way that we can understand.

Why do we all sing so much better in the shower? (Because of the harmonics of the cubicle. We also sound good in the car, but only if all the windows are shut.) Why is the picture on our new wide-screen TV so much worse than it was on the old cathode-ray tube? (Because the same number of pixels are spread over a much larger area. High definition is therefore an answer to a problem that didn’t exist before, and a highly profitable one at that.) I particularly liked Barrow’s analysis of Jackson Pollock’s paintings, which have the highly unusual quality of looking very similar whether you’re 20 yards away, a few feet away or a couple of inches away. Pollock, he says, had an instinctive grasp of fractal geometry, before anyone knew there was such a thing. Computers can now produce images with this quality at the touch of a button; Pollock was decades ahead of them.

Our own Peter Jones, whose ‘Ancient and Modern’ column has adorned The Spectator since people were taught Latin in schools, has now produced Eureka! Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Ancient Greeks But Were Afraid to Ask (Atlantic, £19.99, Spectator Bookshop, £17.99). I love the fact that a book like this exists: populist and inclusive in intention, cultured in execution, and often cheerfully abstruse in content. In 500 BC the Greek city of Sybaris invented the patent, when a chef who had created a particularly delicious dish was granted the sole right to cook it for a year. We think in terms of the Olympic Games, plural, but when they started, in 776 BC, there was only one: the 200 metres. Jones is a storyteller at heart, unashamed to entertain while educating by stealth, as all the best teachers do.

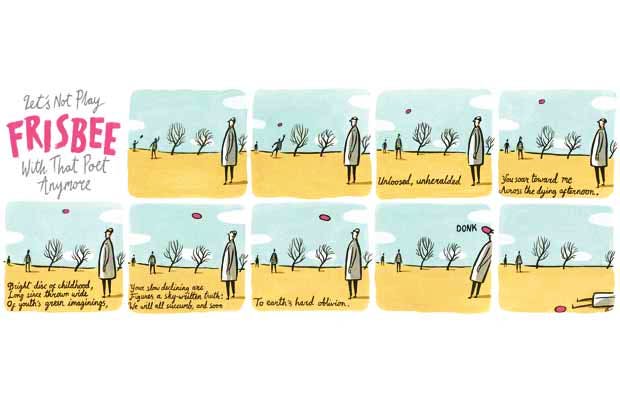

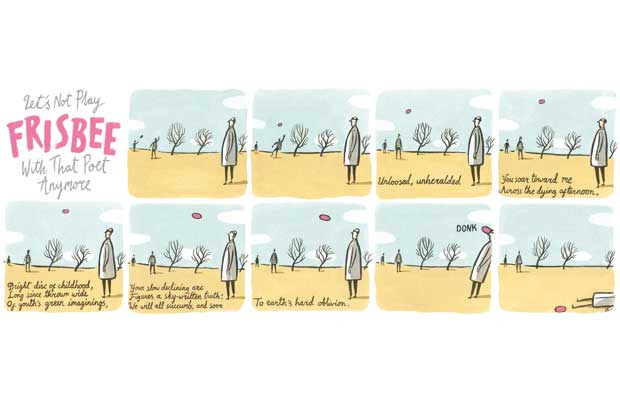

Of cartoon books there seem to be fewer this year, although I am relieved that Canongate’s publication of the Complete Peanuts continues, with Volumes 15, 16, 17 and 18 just out. Otherwise, the outstanding title this year is Stephen Collins’s Some Comics (Cape, £12.99, Spectator Bookshop, £10.99). This brings together his strips from the Guardian’s Weekend magazine, where they sat in the space under Lucy Mangan’s column, until that was removed, possibly for being too amusing and well-written.

Collins’s stick figures are ordinary people trying to deal with incomprehensible, often horrendous circumstances, often drawn from trashy old science-fiction films. But there’s also Buzzfeed Moses, wearing hipster glasses, sitting on Mount Ararat, and chipping onto a stone tablet the words ‘The 10 Things That It Would Literally Be the Worst Thing Ever To Do.’ Badgers plan to infiltrate parliament by hiding in Brian May’s hair. ‘I’m not sure I can go through with this,’ says Brian. ‘Can’t I just do the solo?’ ‘No,’ say the badgers. A woman goes to a rescue centre, sits behind a two-way mirror and chooses a rescue husband from those in the cage. She takes him home, they live together, bring up a family, they grow older, he dies. Then she goes back to the rescue centre and picks another one. Collins is a young man already equipped with the mordant gloom and brutal cynicism of the career cartoonist, and this is a fine first collection.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in