Listen

There should, by rights, have been a stampede of candidates to replace Johann Lamont as the leader of the Scottish Labour party. With the new powers promised to Holyrood, the Scottish First Minister promises to be a more powerful figure than most of the Cabinet. Only the holders of the great offices of state will be more influential than the occupant of Bute House. Labour might well trail the SNP by a large margin in the Holyrood polls, but their position is by no means hopeless.

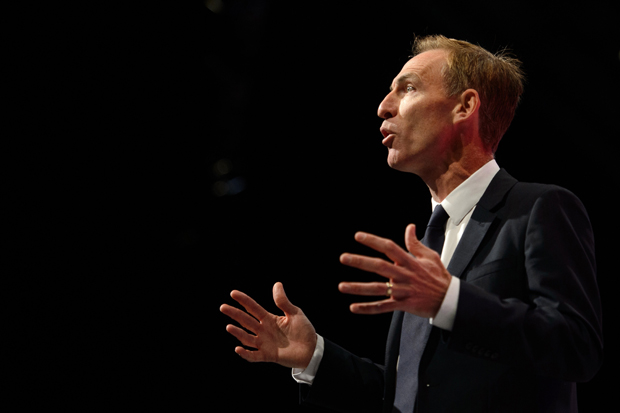

But since she decided to step down, there was silence. After days of deliberation Jim Murphy, the shadow international development secretary, has now thrown his Tam o’Shanter into the ring along with two MSPs: Neil Findlay and Sarah Boyack. Murphy is the frontrunner but he took his time to decide – which is odd when one considers the weakness of his position in Westminster.

Murphy was one of the managers of David Miliband’s leadership campaign, and has never been quite forgiven by Team Ed. He’s been demoted from shadow defence secretary to shadow international development, where it is almost impossible to score any runs because of the level of agreement between Labour and the coalition. The high road back to Scotland should be the noblest prospect that he has ever seen.

It is depressing that devolved office should be seen as a resting place for those who fall down Westminster’s greasy pole. When the Tory leadership was trying to push Boris Johnson into going for the London mayoralty it had to use a reshuffle to make it clear he wouldn’t obtain great office under David Cameron.

It is not as if quitting Westminster need be the end of your national ambitions. Boris Johnson will return to the Commons at the next election and in a far stronger position than if he had never left. It is hard to believe that this magazine’s former editor would be the bookies’ favourite to be the next Tory leader if he had stayed in parliament. He also would not have had the chance to demonstrate that he can run things. Indeed, if Murphy wants to be the leader of the UK Labour party, as some of his admirers and detractors suggest, his best route runs through Holyrood.

But the state of Scottish Labour would give anyone pause about taking on the job. It is reaping what it sowed in the 1980s and 1990s, when it denounced the Tories as fundamentally un-Scottish and as tools of London’s cruel economic agenda. Labour now finds the same rhetoric thrown back at it by the Nationalists. Unsurprisingly, these attacks have had the most success in the Labour heartlands, where this narrative took hold most strongly under Thatcher.

Every parliamentary constituency in Glasgow voted ‘yes’ to independence in the referendum. Now the SNP is determined to redouble its effort in west central Scotland. Its new leader, Nicola Sturgeon, is a Glasgow MSP and a far more conventionally left-wing politician than Alex Salmond. She might not be his match in some areas but she is far better suited to prosecuting this charge into the Labour heartlands.

Many in Scottish Labour, and particularly in the union movement, want the party to move left to counter this threat. Unite and Unison even decided to stay neutral in the referendum as a warning to Labour that it could not take their support for granted.

If Labour did this it would endanger its seats in middle-class Scotland. Its great achievement in 1997 was to add constituencies such as Edinburgh Pentlands, East Renfrewshire and Stirling to its traditional strongholds, leaving the Tories without anywhere to hang their hat. If Labour dashes left in pursuit of Sturgeon, they will create an opportunity for the Tories. Murphy, who won East Renfrewshire — once Scotland’s safest Tory seat — in 1997 will understand the risks of such a strategy. By temperament, instinct and ideology, he is a realist. He is on Labour’s reformist right and it is impossible to imagine him trying to fight on any other ground than the centre. This is why Unite and the Labour left will oppose his candidacy vigorously. Last year, Len McCluskey, secretary-general of Unite, warned that if Miliband was ‘seduced by the Jim Murphys’ of this world he would be ‘defeated and he’ll be cast into the dustbin of history’.

Murphy has what Scottish Labour needs so badly: energy, no fear of the SNP and the ability to win elections. The pro-union campaign often seemed devoid of passion and willing to cede the street theatre of the campaign to the Nationalists. But no one could find Murphy guilty on these counts. His tour of Scotland on Irn-Bru crates was a bravura performance that showed a determination not to be intimidated. It succeeded in exposing the Nationalists’ ugly underbelly; the sight of him being met by mobs determined to shout him down provided a chilling preview of how dissent would be treated in a Nationalist-run Scotland.

Almost as impressive was how Murphy succeeded in winning East Renfrewshire in 1997 on a 14 per cent swing and then turning it into a safe seat; at the last election, he secured 51 per cent of the votes cast. Senior Scottish Tories admit that Murphy will be the MP for East Renfrewshire for as long as he wants. But, they are surprisingly optimistic about their chances if he stepped down.

As a Blairite and a hawk on the Middle East, Murphy will face industrial quantities of abuse. The Nationalists will try to portray him as the ultimate bogeyman.

But if he had not run, he’d have been leaving the fight to lesser politicians – and risked ceding Scottish politics to the Nationalist left and their agenda. This is a risk that Labour cannot afford to take. The party has never gained power at Westminster without winning in Scotland. And with Murphy at the helm, it is far more likely to start winning again.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in