The moment Waterloo Bridge was planned across the Thames, a new theatre to serve the transpontine coach trade was inevitable. The Old Vic opened in 1818. Originally called the Royal Coburg, it could seat a whopping 3,800. Kean was the first great actor to perform there. In 1831 he played Richard III, King Lear and Othello in one week. After giving his Moor, he came on, still blacked up and doubtless drunk, and let the heckling swine have it: ‘I have never acted to such a set of ignorant, unmitigated brutes as I see before me.’ Theatre back then sounds such fun.

The amazing thing about the Old Vic is that it never burned down like all other theatres of its vintage; instead, its story is one of constant financial disaster. Its history features two penny-pinching, remarkable women, neither of whom liked theatre very much. Emma Cons was a well-connected do-gooder but she was passionate about temperance, not theatre. Not once in her 32-year reign did she put on a play.

Her niece, Lilian Baylis, took over in 1912. It was the eccentric, pious Miss Baylis, frying sausages in the wings and using one of the curtained-off boxes as her office, who made the place famous. Her first love was always the opera. Under her regime, however, the Old Vic acquired Shakespeare as its house dramatist. All the plays of the First Folio were staged, and John Gielgud gave his mellifluous Hamlet. ‘Sorry, dear, God says no’ was Baylis’s response to any actor’s request for a pay rise. A populist visionary, she must have seemed to many a stingy old rat-bag.

When Olivier arrived from Hollywood it was a major coup for the Vic. ‘The smell of a leading man to Lilian was like oats to a racehorse’, Larry said. He saw it as his life’s duty to make the National Theatre happen, which eventually he did. This part of Terry Coleman’s book — the theatre’s golden age from 1912 up to 1976 when the National quit the Old Vic — is excellent.

But he is oddly selective with the anecdotes. Why write about Peter Brook’s Oedipus and not include the Coral Browne story? The actress was in the audience. At the end of the show, when a colossal golden phallus was wheeled on, she audibly whispered to her partner, ‘It’s not anyone we know.’

In 1982 ‘Honest’ Ed Mirvish, a Canadian businessman, bought the theatre without ever having seen it, outbidding Andrew Lloyd Webber. Mirvish heroically chucked millions at the Vic, losing most of it. ‘If you ever have the urge to make money, don’t fight it,’ he told his uncommercial artistic director Jonathan Miller.

The American film star Kevin Spacey took over in 2004. A lot of the shows Spacey chose to stage were disappointing and I felt this needed saying. Also, I’d have liked a bit more about why the Old Vic has languished while 100 yards down the road the Young Vic — not even mentioned — has become one of the most exciting theatres in town.

Matthew Warchus is a good choice as Spacey’s successor — he’s a world-class director and no theatre snob. Coleman covers a lot of ground in this canter of a survey, and has a sharp journalistic eye for detail. But it feels thin and lacking in judgment once you pass the Olivier years.

The biographer and theatre journalist Jonathan Croall — he was journo-in-

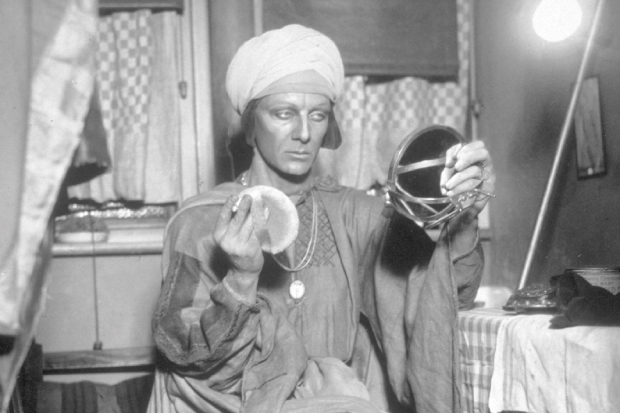

residence at the National and the Old Vic — has collected over 50 pieces in Closely Observed Theatre, specialising in the eavesdrop. He sits in on rehearsals and talks to actors, writers and directors. His observations of the working processes of Howard Davies and Robert Altman are intriguing. But I grew a little tired of his enthralment to the artistes he interviews. In 2004 some serious thesps thought they’d do Aladdin at the Old Vic with Ian McKellen playing Widow

Twankey. The show is gone into in considerable detail, but Croall misses the key point — the panto was a dud and the actors embarrassing when they tried to slum it in false tits. The book left me craving the red meat of some critically negative opinion.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

'The Old Vic', £20 and 'Closely Observed Theatre', £9.99 are available from the Spectator Bookshop, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in