Giovanni Battista Moroni, wrote Bernard Berenson, was ‘the only mere portrait painter that Italy has ever produced’. Indeed, Berenson continued, warming to his theme, ‘even in later times, and in periods of miserable decline, that country, Mother of the arts, never had a son so uninventive, nay, so palsied, directly the model failed him’. It was a harsh judgment, but the great connoisseur inadvertently managed to put his finger on exactly what was so marvellous about his victim.

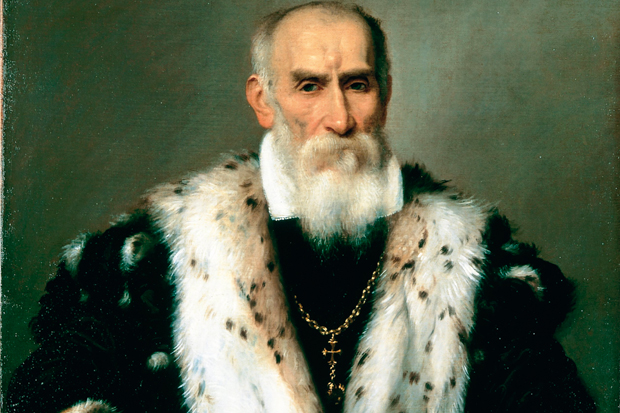

A splendid exhibition at the Royal Academy triumphantly demonstrates that when Moroni actually did have a model in front of him, he was one of the most remarkable painters of later 16th-century Europe. He was, however, one who does not seem to fit easily into his time and place.

A fellow visitor turned to me while I was gazing at the wonderful ‘Portrait of an Elderly Man Seated with a Book’ (c. 1575–9) and remarked, ‘It’s hard not to think one is looking at a 19th-century picture.’ He was dead right (which in turn helps to explain why Moroni appealed so much to the Victorians, and consequently why the National Gallery has such a magnificent array of his work). The sobriety, the warts-and-all candour, the carefully depicted detail — all of these give a powerful impression of absolute realism.

Moroni (c.1520/4–1579) actually included, if not the warts, certainly bulbous facial protrusions such as the bump in the centre of the august forehead of Gian Girolamo Albani, an aristocratic sitter. This refusal to flatter, however, is just an aspect of the truthfulness that makes one feel, in front of any of the portraits, that this is exactly what a particular person, who lived four and a half centuries ago, really looked like. Such accuracy, of course, was a 19th-century virtue.

The ‘Portrait of an Elderly Man’ (c.1575), dressed in black and seated in a chair against a neutral grey background, is reminiscent of Whistler’s Carlyle — except that the Moroni projects a much more powerful sense of personality. In different ways many of the superb array of portraits in the exhibition do the same. The ‘Elderly Man’ fixes you with a look of disconcerting intensity. The Spanish ‘Don Gabriel de la Cueva’ (1560), with sword prominently on display and motto announcing his fearlessness, could be a feuding hothead from Romeo and Juliet (the nobles of Bergamo were as prone to murderous vendetta as those of nearby Verona).

In contrast, ‘Giovanni Gerolamo Grumelli’ (1560) seems diffidently awkward in his splendid but faintly absurd pink outfit. The latter is, as always with Moroni, wonderfully painted, with painstaking attention to cut and texture of cloth; it was not an accident that one of his most memorable pictures was of a tailor — perhaps a friend. Moroni was plainly fascinated by clothes.

Among Moroni’s contemporaries even Titian, great portrait painter though he was, does not quite convince in this way. But part of Titian’s professional skill was introducing subtle improvement into his sitter’s appearance (for example, brilliantly transforming the Emperor Charles V’s grotesquely projecting jaw into an emblem of nobility). There Titian was in the mainstream of Renaissance art, which depended on a deft blend of naturalism and idealisation.

Moroni was out of that mainstream. He came from the Northern Alpine border of the Italian world. Born in the town of Albino, he worked there and in nearby Bergamo, Brescia and Trento. The catalogue points out that Vasari, author of the most influential of all books on Renaissance art, did not bother to visit Bergamo, which might be why he failed to mention Moroni.

The sharply focused precision of his work puts one in mind of a northern European painter such as Holbein, but Moroni’s paint is more beautifully thick and creamy in the Venetian manner. On the other hand, he did not have Titian’s or Veronese’s ability to create imaginatively convincing religious art. Berenson was right about that: without a model he was lost.

The discrepancy is almost comic in pictures such as ‘Gentleman in Contemplation of the Baptism of Christ’ (c. 1555). It shows a man in prayer, wonderfully portrayed if more bored than pious in demeanour. He is praying to a vision of Christ and St John that could hardly be more vapid.

True, Moroni was operating in a difficult environment for a Catholic artist. The Council of Trent was on a mission to clamp down on flourishes of fanciful imagination in pious images. This was the era in which the nudes in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement had their private parts censored with wisps of cloth and furry jockstraps. But even so, without a model Moroni was stunningly dull.

Berenson was right about that but he did not understand that a mere portrait painter can also be a great artist, as this exhibition makes so enjoyably clear.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in