It’s always interesting when people succeed in two different arenas — like Mike Nesmith’s mum, who gave the world both a Monkee and Tippex, or Hedy Lamarr, the beautiful film star who also helped develop wireless communication, or Paul Winchell, the voice of Tigger who also invented the artificial heart. (If only he’d played the Tin Man in The Wizard Of Oz!) William Moulton Marston created both the cartoon heroine Wonder Woman and the lie detector machine, though by the time I had finished this book I was wondering how he found the time or the energy to do either.

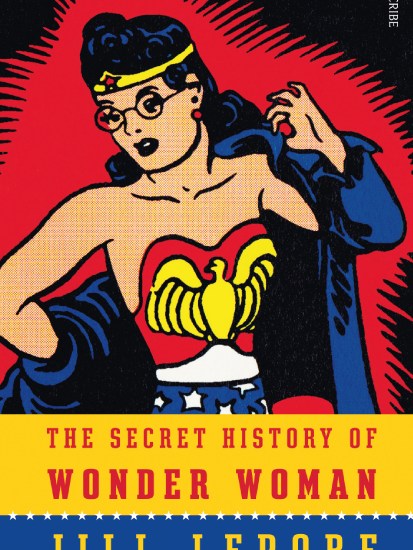

To my generation, Wonder Woman is most famous for being played by the former Miss World USA Lynda Carter in the 1970s television series, wearing the bare minimum of pre-watershed clothing; a patriotic pin-up girl, as the theme song explained; ‘In your satin tights, fighting for your rights — and the red, white and blue!’ But she was conceived by Marston as a feminist symbol, an Amazon from a man-free land who ‘came to the United States to fight for peace, justice and women’s rights’. It’s a bit like finding out that Barbie was a post-dated Pankhurst plant to get women into the workplace.

Coincidentally I was reading a book called Born Liars: Why We Can’t Live Without Deceit when this hefty tome rocked up, and was just embarking on the section about Marston himself. Describing him as ‘irrepressibly optimistic’, it goes on to claim that the lie detector, or ‘polygraph machine’ as it was more pompously known, was so useless that in 1986 when Aldrich Ames, a CIA operative spying for the USSR, informed his paymasters that the government intended to give him a routine polygraph test, they simply advised him to get a good night’s sleep and relax. He did so and passed — and passed again, in 1991, when the CIA were carrying out a search for an internal mole (i.e. Ames himself).

We generally think of snake-oil salesmen as coming from humble origins and turning into fantabulists through financial greed, but Marston’s was a full-on blue-blooded Bostonian background with the flashes of pure American gothic such a heritage often holds. His mother was one of five sisters whose father, after the only son of the family had died, built a whole turreted medieval-mode mansion and closeted himself in the tallest of its towers to write a treatise entitled The Moulton Annals, in which he traced his family back to the Battle of Hastings. His grandson would carry on these traditions of eccentricity and self-importance; the book starts weird and gets weirder.

For instance, WMM married his teenage sweetheart, bluestocking Sadie, who he puzzlingly calls ‘Betty’ — but then set up a ménage à trois with a young suffragette student of his, Olive Byrne, giving his allegedly feminist wife an ultimatum to join in or bail out. (There they are, in Olive’s graduation

photographs, looking creepily like her parents.)

Reading this, I was reminded of Russell Brand’s brand of revolutionary talk and old-school alpha-male sexism, and of smug men wearing ‘This is What a Feminist Looks Like’ T-shirts, and of The Handmaid’s Tale. Olive Byrne never finished her PhD because she was too busy bringing up the Marston baby.

Still, the trio must have had their fun along the way — they were right goers, and kinky as all get-out. An unusual amount of Marston’s research seemed to involve ‘restraining’ women and Wonder Woman ends up bound and/or caged more often than you might think credible even for your average superhero. Early in the book, Olive the student takes her professor Marston to a sorority initiation where inductees were required to dress up as babies, be blindfolded and beaten with long sticks. (And I thought my comp was rough!)

Lepore’s voice is fresh, clear and often cheeky despite its scholarliness; ‘It sounds a little filthy,’ she remarks of a poem the young Marston sent his wife. This is a truly gorgeous book — beautiful to have and to hold, with lovely little black-and-white photos on most pages — as well as a sumptuous colour cartoon section. It is brilliantly written and splendidly researched. As well as learning lots about Wonder Woman, I picked up many fascinating facts about 20th-century social history: for instance, that all feminists were suffragettes but not all suffragettes were feminists; psychology started as a branch of philosophy; the Age of Aquarius was invented in 1908, not by the Sixties musical Hair; most members of the orginal Birth Control League were Republicans and Rotarians; the word ‘gay’ to indicate a (female) homosexual orginated in the 1920s, not in modern times, despite the fuming of uptight busybodies in the 1970s about how the English language was being robbed of a fine, innocent word by a bunch of in-crowd inverts; Margaret Sanger, the pioneer birth-control fan, married a millionaire in order to finance her feminist crusading — talk about taking one for the team.

‘One tragedy of feminism in the 20th century was the way its history seemed to be disappearing,’ Lepore writes in the final chapter; as anyone with the slightly knowledge of feminism today knows, this is still true. She refers to ‘feminists trashing each other’ in the 1970s and 1980s; they still are. It could be seen as the world’s longest cat-fight — or simply as proof that women are as individual as men.

One of the modern battles is between anti-porn crusaders and pro-porn suck-ups; one wonders what side Marston would have been on. What a shame his harem didn’t try out his polygraph test on him. Because surely even such a gimcrack gimmick could have told them that Marston’s plans for women were far more to do with his getting his end away than their achieving equality. WMM hog-tied by his own creation’s Golden Lasso of Truth; that would have been a sight worth seeing.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in