It is a strange paradox of our egalitarian age that a progressive publisher like Penguin should commission — at considerable expense, since the series editor Simon Winder has netted some top academic authors — brief lives of all 44 English, and later British, monarchs, from Athelstan to his distant descendent, our own Queen Elizabeth. The 45th book in the series is devoted to our sole non-royal ruler, Oliver Cromwell.

The biographies — each costing £10.99 — though not exactly ‘potted’, are necessarily squeezed by space — none is longer than 150 pages — into extended essays that can be comfortably devoured in a couple of hours; ideal for a railway journey or a short-haul flight in our cash-rich, time-poor era. In the hands of the right practitioner, however, this brevity can be a blessing: witness the mastery of the form by John Aubrey or Lytton Strachey. And with less skilled writers, at least we know that the pain will not last long.

One problem with such a series, apart from Penguin’s surely reluctant royalism, is that as the power and prestige of the crown declined, the monarchs tended to become merely decorative objects. Worthy symbols rather than living, breathing people: the kings, as it were, morphed into cabbages.

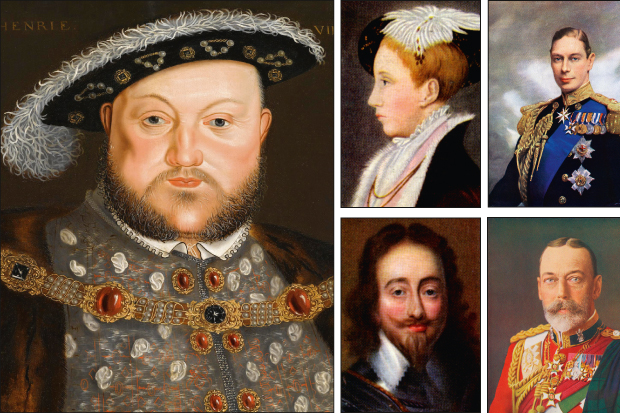

This does not matter too much in the case of arguably our most boring, but also our most popular, sovereign. George V by David Cannadine (121 pages) shines because Cannadine is such a sparkling writer that he makes even decent old George glitter with his biographer’s reflected glory. A dull dog George may have been, but with Sir David’s scattering of stardust, even the king’s most consuming interest, his stamp collection, commands our attention. Well, almost.

Like his second son and successor, George V was not born to be king. His elder brother, Prince Albert Victor, also known as Prince Eddy, was the heir, and as the spare George was little regarded until pneumonia carried off his brother in 1892. Since Eddy had been plausibly linked to a gay brothel in the Cleveland Street scandal, and was also suspected by conspiracy theorists of being Jack the Ripper, it is likely that had he lived his reign would have been less respectable than that of his brother, but probably more interesting.

It is doubtful, however, that an un-stable Eddy could have withstood the

world-shaking shocks that the stolidly unimaginative George did — the suffragettes; industrial unrest; civil war in Ireland; the first world war and the downfall of his cousins Tsar Nicky Romanov and Kaiser Willy Hohenzollern; the rise of fascism, Nazism, communism and the Great Depression. George not only ensured the survival of his German dynasty — reinvented as the House of Windsor — but its triumphant apotheosis when he celebrated his silver jubilee in 1935, just before his death. He was amazed by the affection shown by the celebrating crowds. ‘After all, I am a very ordinary fellow,’ he said. He was — and in the age of the common man that was all that was needed.

After the blip of the abdication it was the turn of our most reluctant monarch to mount the throne with faltering footsteps. George VI by Philip Ziegler (94 pages) shows George as a chip off the old block: the same naval background as his father; the same lack of training for his role; the same dogged devotion to duty (Ziegler dubs him ‘George the dutiful’); the same happy marriage; the same cautious conservatism; the same desire to ameliorate class conflict — and, it must be said, the same limited intellectual ability.

Apart from his famous stammer and his stubborn attachment to the men of Munich and appeasement, George was an ideal king for an era when the monarchy was becoming a puppet show: a powerless unifying figurehead to get the nation through another world war. In fact his agonising speech defect may actually have aided his popularity. As George’s daughter Elizabeth has so eloquently exemplified, but his grandson Charles may never learn, for a successful modern monarch, silence is golden. Ziegler’s simple verdict on his sovereign is a just one: ‘He was a good king. More important than that, he was a good man.’

One monarch from the days when kings mattered who was indisputably not a good man, though his biographer, John Guy, judges him (in 141 pages) to have been ‘the most remarkable ruler ever to have sat on an English throne’ was Henry VIII — he of the six wives, pustular thighs and piggy eyes. Considering the mayhem Henry unleashed when he founded the Church of England essentially to get his diseased leg over Anne Boleyn, Guy takes a tolerantly sanguine view of this bloated, 54-inch-waisted monster.

Guy divides the man and his reign. Early good Henry is the fabulous renaissance prince: learned, courtly, musical, sporty, the friend of More and Erasmus, and the pious upholder of Catholic tradition — the original ‘Defender of the Faith’. Late bad Henry is the obese, paranoid, stinking wreck, whose bulky, leaky hulk had to be hauled around on commodes by pulleys: an English Stalin who destroyed not only his church and his unfortunate queens, but also the statesmen — Wolsey, Cromwell and More — who had made his England one of Europe’s great powers.

Stephen Alford’s Edward VI (98 pages), is an oddly lopsided production on Henry’s longed-for legitimate son. Dazzled by the colourful pageantry of the boy king’s short reign, Professor Alford — curiously for such a distinguished Tudor scholar — gives us scant information about what was really significant in Edward’s life: his fanatically Protestant religious policy. We learn next to nothing of the radical Reformation that sparked two major rebellions and would have made England an austere Calvinist stronghold, Switzerland without the Alps, had not the lad died before it could be completed.

More curious still is Mark Kishlansky’s provocative and doomed attempt to positively ‘re-balance’ history’s negative assessment of Charles I (in 120 pages), even though he admits that his reign was the most disastrous in English history. His euphemistic description of a civil war caused by the ‘Man of Blood’ that killed more than 12 per cent of the population is ‘unprecedented political agitation’.

In his misplaced revision Kishlansky perpetrates blatant historical howlers, denying that his hero was ‘perfidious’. Charles lied to his friends and enemies alike, and assured the Earl of Strafford ‘upon the word of a king’ that he would ‘suffer neither in life, fortune or estate’ — shortly before signing his loyal servant’s death warrant. Claiming that the king was a model of marital fidelity, Kishlansky seems unaware of the discovery of letters in cipher from Charles while immured in Carisbrooke Castle, referring to his ‘swiving’ the aptly named Jane Whorwood.

Kishlansky’s statement that Charles’s final defeat at Naseby ‘could easily have turned in the king’s favour’ is nonsense. The ragtag royalists were outnumbered 2-1 by the professional New Model Army and even the fiery Prince Rupert counselled against giving battle. The truth about Charles was told by his close associate Archbishop Laud, who said of his master that he ‘neither knew how to be, nor how to be made, great’. To be blunt, King Charles was a cabbage.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Penguin’s series on our monarchs — from Athelstan to Elizabeth II — will be completed in 2017. These first titles are available from the Spectator Bookshop at £9.49 each or £45 for all five.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in