Great works of art may have a strange afterlife. Deracinated from the world that created them they are at the mercy of what people think is important centuries later. Nothing shows this more clearly than the contribution that Tallis’s ‘Spem in alium’ has made to Fifty Shades of Grey.

In case you are none the wiser, ‘Spem in alium’ is probably the most complex piece of music to come from the 16th century, and just possibly from any century. Written for 40 independent voices, it is unlikely to be sung with every note in place, though any sort of approximation shows just how majestic it is. Whether this was in the mind of E.L. James when she had her lovers do what they liked to do while listening to it, I cannot say; but its title is mentioned in the book, and the Tallis Scholars’ recording did very nicely on the back of it. I have been asked repeatedly in interviews what I thought of coupling a work of high art with S&M, to which I replied that it doesn’t matter to me how people encounter Tallis, as long as they do. My favourite interview on this topic was in Rome, in Italian, from which I learnt some vocabulary I didn’t know before.

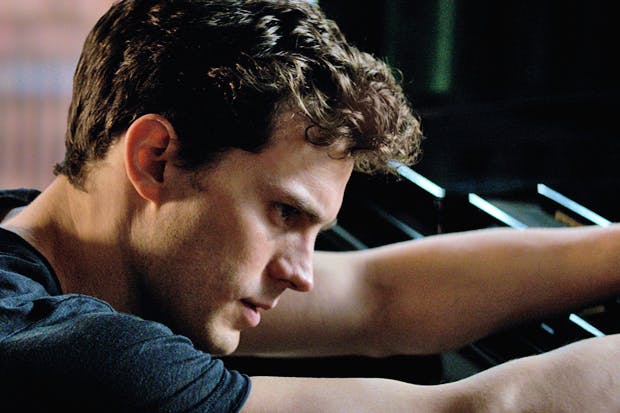

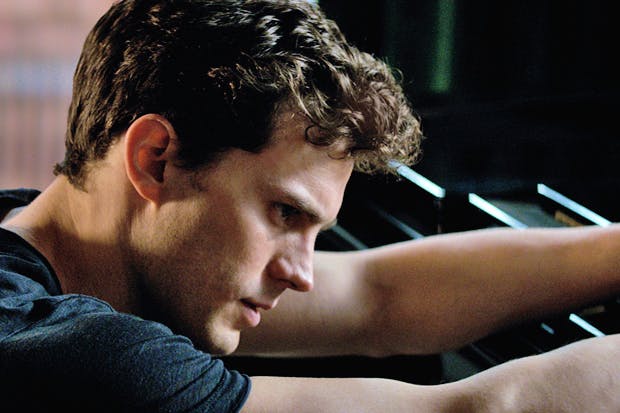

Rather than pay for a proper recording of the Tallis, the directors of the new film commissioned a spoof version of it, which involves some token voice-leading over a backing track, before it is interrupted by a cello. The only piece of classical music referred to in the book that properly survives into the film is a snippet of Chopin, which Grey himself is pretending to play on the piano. Otherwise it is a question of dumbing down the references to an easy-listening sequence of low-brow mediocrity, which does nothing to raise the achievement of a film already stripped bare of vibrancy. Why do this? James did well with her music — Bach, Fauré, Verdi, Rachmaninov, Vaughan Williams as well as Tallis were all mentioned. There was a hint of class, now lost.

At the other end of the spectrum was the performance of ‘Spem in alium’ I conducted at Ted Hughes’s memorial service in Westminster Abbey in May 1999. What to say about a piece of music written 450 years ago which, without the services of a hip publicist, can both qualify for embellishing a sex scene and for performance at the memorial of the poet laureate, where it fell to us to sing Tallis’s colossus.

Hughes’s memorial stone has only been in place in Poets’ Corner since late 2011; but standing by it recently, and reading the inscription — ‘So we found the end of our journey/ So we stood alive in the river of light/ Among the creatures of light, creatures of light’ — I was instantly taken back to the final 20 bars of that ‘Spem’, written for 40 voices uninterruptedly. It ends in a blaze of light, though the words do not suggest this. My main concern at the time was that the Queen Mother, aged 98 and sitting perilously close to the front line of singers, would not be blown back down the nave she had so steadfastly walked up a few moments earlier. Of course, the Abbey is as good a place as any for such a massive affirmation of the human spirit, though I couldn’t help noticing, as we stood there arrayed on the altar steps and projecting our sound down the length of the building, that the acoustics are in fact quite dry. It may go against the grain to say so, but ideally I would choose to perform such resonant pieces in a modern building with a controlled sound, like the Birmingham Symphony Hall. Anyway it wouldn’t surprise me if Christian Grey had had the volume on low. There is no cooing after those last 20 bars at full throttle.

‘Spem’ was preceded at the memorial service by a recording of Ted reading the ‘Song from Cymbeline’ — ‘Fear no more the heat o’ th’ sun’. This was introduced by Seamus Heaney, who previously had read Hughes’s ‘Anniversary’. Alfred Brendel played the Adagio from Beethoven’s Op.31 no. 2. There were further tributes and readings from Ted’s work: ‘Fern’, ‘That Morning’, ‘Pibroch’, ‘February’. Bach’s G major Prelude and Fugue rounded off the service.

So there you have it. A work of unparalleled mathematical complexity, of occluded emotional charge, which appeals to intellects of very different kinds. How is it possible for mathematical constructs to have such appeal? How did Bach do it, or Josquin, or Richard Strauss? I don’t know; but I find something heartening in the story I have just told, S&M or no.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in