One of the curiosities of western art is that, until the 20th century, few visual artists were of Jewish ancestry. With odd exceptions such as the Pissarros and Simeon Solomon, the culture tended to produce verbal rather than visual imaginations. With the 20th century that changed. The important group of abstract expressionists that came out of New York after the second world war centred on at least two Jewish artists — Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko.

Both possessed a specifically Jewish imagination, and both narrowed down their pictorial language to forms that expressed mystical aspects of their ancestral culture and faith. In Newman’s case it was the ‘zip’, a thin vertical stripe in a colour field connecting Earth and Heaven. In Rothko’s work, after a long period exploring figurative, surrealist and mythical imagery, it was made up of horizontal colour fields floating and dissolving, placed above each other in unpredictable and absorbing proportions.

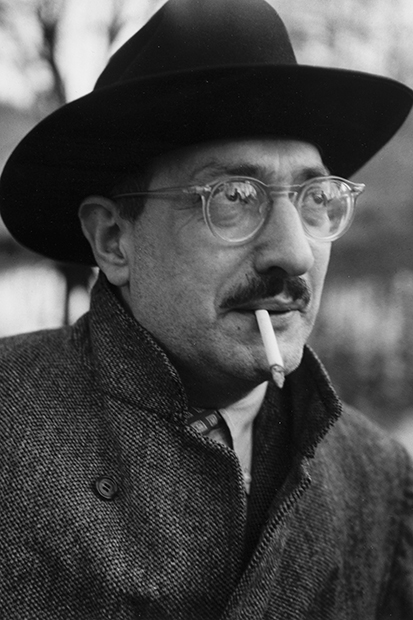

Quite why Jewish artists emerged at this point and not earlier is an interesting question, addressed to some extent in Annie Cohen-Solal’s new volume in Yale’s ‘Jewish Lives’ series. Many people have discerned a strain of mysticism in Rothko’s mature works — the American abstract expressionist Clyfford Still described him as ‘thoroughly immersed in Jewish culture’. Cohen-Solal is able to be quite specific about this, claiming that individual parts of Rothko’s Seagram murals ‘may recall letters of the Hebrew alphabet: gimel, samekh and mem sophit’. If that is the case, it would explain why a painter of this sort could most easily emerge from minimalist abstraction.

Another explanation might be that artists like Rothko and Newman, whose works seem to require some degree of explanation from a professional, would emerge most naturally from a culture at ease with the practice of exegesis and of exegetes working on commentaries and commenting on each other in turn. Talmudic scholars and critics of abstract art have a good deal in common, including the ability to write at length about what, to the casual observer, isn’t there at all.

Rothko was born Marcus Rotkovitch in Dvinsk (now Daugavpils), a town in Latvia where outbreaks of hideous violence against Jews were common. In 1913, his father Jacob, an educated pharmacist. succeeded in settling with his family in Portland, Oregon; Marcus arrived with a helpful placard hung round his neck reading, ‘I do not speak English.’ He grew up in a community that Cohen-Solal pleasingly evokes:

They bought their bread at Harry Mosler’s bakery on First Avenue at the corner of Caruthers; their cheeses at Calisto and Halperin…their meat from either Simon Director, Isaac Friedman or Joseph Nudelman, the three kosher butchers. Their hair was cut by Wolf the barber, their teeth were checked by Dr Labby the dentist, and they spent their Saturday evenings in the Gem Theatre on Sheridan or in the Berg Theatre on Grant,, both of which showed silent movies for five cents.

Marcus’s education was successful enough to get him into Yale, although his father, who ran an Old World Drug Store and Ice Creamery in ‘Little Odessa’, was far from rich. Yale was seeing plenty of able Jewish students at that time, and didn’t much like it: the dean wanted to ‘put a ban on the Jews’. Perhaps because of this, Rothkovitz (as he now was) dropped out after two years. It was only in 1923 that he first came across life-drawing, and embarked on lessons. By 1928, he was making money as an artist, was included in a group exhibition, and in 1929 was appointed drawing instructor at the Brooklyn Jewish Center’s art academy, a job he kept until 1952.

Modernism in the shape of the Manhattan Armory Show had reached America six months before Rothkovitz’s own arrival. Before making his unique contribution to art, Rothko (as he finally became in the 1930s) made his name by picking fights, arguing with institutions, forming impassioned alliances called things like ‘The Ten’ (there were nine in the group) and bewildering patrons by rudely refusing commissions — a practice he would maintain all his life.

Rothko’s canvases from this period were grandiose in concept, with titles such as ‘Antigone’ and ‘The Omen of the Eagles’. These paintings don’t really work, but they were starting to gain a lot of attention. Barnett Newman, who wrote in 1942 that America would soon ‘become the cultural centre of the world’, was also attracting interest, along with Jackson Pollock and Clyfford Still. The American critical establishment seemed ready for such artists, even before they had developed their distinctive style, and the four exhibited at Betty Parsons’s famously avant-garde gallery.

By 1949, Rothko had begun to paint the great floating abstracts of dissolving oblongs that would make his reputation for posterity. He was always secretive about the processes he used to create these remarkable, glowing, depth-filled canvases, and it is only quite recently that technical analysis has established that he was experimenting with egg tempera as well as oil and acrylic. He was as perverse and puzzling as ever in his engagements with the art world, insisting that he didn’t want to be shown in institutions — which he thought would make him look too decorative — but only in a private context. ‘I’ve come to believe that no painting should ever be displayed in a public place,’ he once pronounced.

Though in 1958 he did accept a major commission to paint murals for the Four Seasons restaurant in Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram building (saying he ‘hoped to paint something that will ruin the appetite for every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room’), he soon changed his mind and returned the huge advance, keeping the paintings. Nine now hang in Tate Modern. By 1957 his canvases were selling for $5,000 each, a figure which depressed him then and which has only risen steadily since his death.

They are marvellous paintings, for which no reproduction prepares you, and which are best seen in certain conditions, wonderfully described by Bryan Robertson, an early English supporter:

Rothko asked me to switch all the lights off, everywhere [in the Whitechapel Gallery]; and suddenly, Rothko’s colour made its own light: the effect, once the retina had adjusted itself, was unforgettable, smouldering and blazing and glowing softly from the walls — colour in darkness.

Failing that, the perfect subdued light in the Menil Chapel in Houston, a building constructed to hold Rothko’s last and most overwhelming series, gives some sense of these ideal circumstances.

His life ended in chaos and depression: abandoning his wife in 1969, he moved into his studio, where he was found dead the following year, having overdosed on anti-depressants. His teenage daughter was left to try to recoup the estate from the grip of his executor and some brutally ambitious gallerists — whose conduct was ultimately described in court as ‘manifestly wrong and indeed shocking’.

Rothko’s children recently funded the establishment in Daugavpils not only of a Rothko Centre but also of a synagogue — there wasn’t one. At the time of their father’s birth there had been 50.

Annie Cohen-Solal has written an interesting study of Rothko’s intellectual influences, which betrays her French origins only in her minor addiction to absurd rhetorical questions such as: ‘What if the virulence of the Ten had been triggered by decades of indifference and passivity toward art, in a country marked for too long by philistinism?’ Well, what if not? But it’s a good way into this cryptic and argumentative painter, whose moods are often painfully apparent in his art — a vivid orange on chocolate; a deep, glowing, angry purple on black.

His popularity is perhaps baffling, but irresistible — though it was much resisted by Rothko himself while he was able. His own attitude to the physical appearance of things might be more complicated than anyone can now explain. John Hoyland observed, tantalisingly, that ‘I doubt if he even liked his own appearance very much.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in