Sometimes a guy feels abstracted from the world. He visits Europe’s finest galleries, but the paintings seem to hang like corpses from the walls. The great symphonies fail to stir his interest, let alone his soul. So he goes home, pours a large whisky and does the only thing that’s left for him — he buys a PlayStation.

That’s what I did last year, and I’ve been wired to my screen ever since. Parachuting from skies to impale some oblivious mercenary. Driving off buildings to escape the cops. Shooting and shooting — and shooting. Why haven’t I done this all my life?

It was blockbuster games such as Grand Theft Auto that drew me in, but something else held my attention. There, in the PlayStation’s digital shop, are games that you won’t see advertised on the sides of buses. Each costs about five or ten pounds. And each is made by a handful of people, independently of the major gaming studios.

These indie games may be less expensive, but they offer more than just cheap thrills. One called Never Alone was made in conjunction with the Inupiat people of Alaska. It involves guiding a girl and her Arctic fox through the snow. The whites, greys and greens massage your retinas, while the soundtrack conjures aurorae in your mind. Jump, jump, weave and climb. You’ve probably never met an Inupiaq before, but here you are playing through their folklore.

But if that sounds too Greenpeace for your liking, there are plenty of other indie games to try. How about Resogun, a crazy Space Invaders for our crazy times? Or Fez, in which you bounce your character between two dimensions and three? There is even one that lets the player poke a scalpel around someone’s innards.

It must be what New York felt like for cinephiles in 1959. John Cassavetes’s Shadows had just been screened at Cinema 16, and suddenly every American knew that films could be made outside of Hollywood. A hundred thousand other independent movies followed. Some were great, others were as lousy as you’d expect from a bunch of amateurs with cheap handheld cameras. But — gosh! — just the very idea of it. People creating what they want to create.

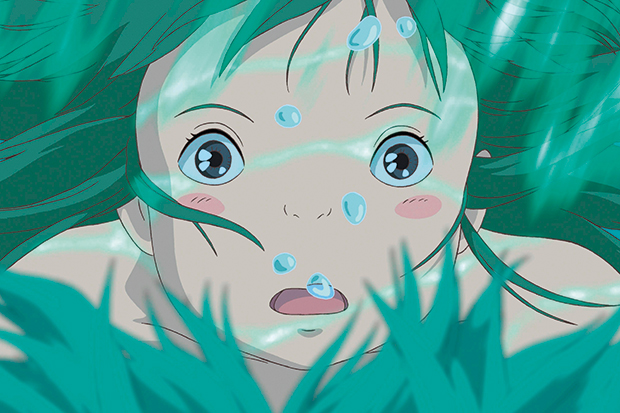

This is the joy of indie games. Some of them are as lousy as you’d expect from amateurs stringing together lines of code in their bedrooms, but the great ones are great because they are personal. Indie programmers don’t just have the freedom to invent; they have to if they want to stand out alongside Grand Theft Auto and its colossal marketing budget. And so we get Monument Valley, in which you swipe a faceless girl through a dreamscape that’s equal parts M.C. Escher and Arabian Nights. Extra care is taken with the story and gameplay precisely because these creators care.

Why this new direction? Although video games have been made by individuals since their prehistory, it’s now easier to do so. There exist simple programs by which almost anyone can create a game. And the internet offers limitless space in which to peddle the end results and then beam them into our homes.

The internet offers another opportunity for wannabe game designers: crowdfunding. So far, more than £300 million has been donated by fans online to fund video games. It’s the most popular category on Kickstarter by tens of millions of dollars.

But how much cash does it take for indies to stop being indies? Much as happened with independent movies, the lines are becoming blurred. Rovio Entertainment started off as three students from Helsinki. But after selling countless copies of Angry Birds it has expanded far beyond that. It is now a major studio in its own right.

This hasn’t gone unnoticed by the existing studios, who are beginning to grow their own indie-style cells. And why not? These games can achieve the perfect corporate mix of cheaper and better. Just look to Child of Light. This was developed by one of the big boys, but it shares qualities with the small upstarts. Like Never Alone, it has you directing a girl and her companion, a ball of light, through a fairy-tale landscape, and it is as beautiful as it is simple.

Or perhaps, rather than bothering to make these games, the old crowd will simply buy them out. Microsoft did exactly that, paying $2.5 billion to acquire Mojang, creators of Minecraft, in 2014. This Swedish company didn’t exist five years ago. Now its principal founder is kicking back in Beverly Hills’s most expensive home. This weird amalgamation of boardroom and bedroom may perturb those who want to keep the independent flame alight. But, with games as straight-up artistic as Monument Valley, there’s no cause for fear just yet. All you have to do is download them and marvel. This is where the culture’s at.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in