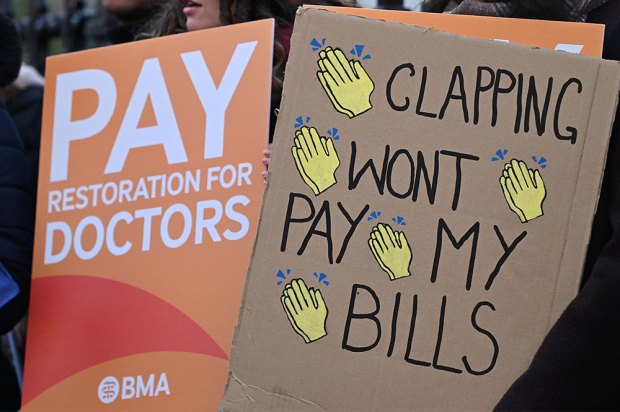

To adapt Aeschylus’s aphorism on war and truth, the first casualty in a general election campaign is objectivity. Over the next eight weeks NHS staff can expect nothing but saccharine praise from politicians who are falling over themselves to say how wonderful the health service is, how committed they are to it. The Conservatives may revive their ‘NH-yes’ slogan, promising to safeguard its budget. Labour proposes to protect it from what few reforms the Conservatives promise and even Ukip is posing as ‘the party of the NHS’.

A true friend of the NHS, however, would accept that all is not well, and that ‘protecting’ its current structure is an act of cruelty rather than kindness. We saw why this week in Bill Kirkup’s report into the scandal of the unnecessary deaths of 11 babies and one mother at the maternity unit of Furness General Hospital between 2004 and 2013. The unit, he concludes, was ‘dysfunctional’, with staff ‘deficient in skills and knowledge’. One baby, Joshua Titcombe, succumbed to an infection which staff had ample opportunity to diagnose but failed to do so.

Expectant mothers with dangerous conditions were sent home with inadequate treatment. On one occasion an epidural injection — supposed to be given into the spine — was administered intravenously. Bureaucratic edicts crushed the common sense of nurses: a policy of insisting on natural childbirth was pursued ‘at any cost’, even when circumstances ought to have demanded a caesarean.

But worse than any of these errors, in some respects, was the failure of the Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust, which runs Furness and two other general hospitals, to recognise that there was a problem. The author of an ‘independent’ report commissioned by the trust was instructed not to revisit the circumstances of serious incidents. Midwives rallied round and covered for each others’ failures, referring to themselves as the ‘musketeers’. The ‘maternity risk manager’, whose job should have been to eradicate bad practice, also acted as a representative for colleagues who had made errors.

Of course, the problems at Furness General, like those at Stafford Hospital, need to be put into perspective. Any large organisation, public and private, is going to have poorly performing elements — and the NHS is now the fifth-largest organisation on the planet.

The service cannot be defined by its mistakes. But what matters is how organisations respond when things go wrong. If Furness General were a privately run hospital, it would be unlikely to survive; just look what happened to Winterbourne View, the privately run home for special needs adults in Bristol, which closed after revelations of physical abuse. And rightly so: its closure sent a message to other organisations about the price exacted for failing those in their care. Yet when bad things happen in the public sector, aside from a resignation or two the institution carries on as before, just with ‘tightened procedures’. If Furness General was slated for closure, the local population would almost certainly rally to save it, as the people of Stafford did. As in Stafford, patients who had criticised care at the hospital might well find themselves ostracised. This is the brutal politics of healthcare: no one wants a local hospital unit to close, even if there is a clear case for driving patients further down the road to a better-resourced unit with higher success rates.

Nigel Lawson, a former editor of this magazine, declared that the NHS is the ‘closest thing the English have to a religion’. It isn’t just midwives and administrators who, to use Kirkup’s words, are in ‘denial’ about failures in the NHS. The politicians who oversee it are similarly disinclined to speak honestly. They find it extremely difficult to criticise doctors or nurses — though will have an occasional crack at bureaucrats. They try to pretend that the NHS can offer everyone everything, regardless of cost, when in reality rationing is taking place, always has done and always will do.

Even Conservatives who have backed the wholesale privatisation of other public services find it extremely difficult to speak up for a greater range of healthcare providers. David Cameron came into office promising no more ‘top-down reorganisation’ of the NHS, yet had not worked out that his Health Secretary proposed to do just that, spending £3 billion replacing primary care trusts with remarkably similar bodies called clinical commissioning groups. Yet the boundaries of the NHS have hardly shifted: since the election the proportion of NHS services provided by independent companies has risen from 5 per cent to 6 per cent.

That barely perceptible shift is what Labour’s health spokesman, Andy Burnham, laughably likes to call ‘privatisation’ of the NHS. Yet even this token amount of wider healthcare provision is under threat from Labour.

NHS reform ought to be a Conservative selling point. The party ought to be able to point at creaking hospitals and pledge, as they did with other public services, to remedy this by innovating. There is no need to compromise the principle of healthcare that is free at the point of delivery. Reform just means saying that healthcare does not need to be provided entirely through one monolithic state bureaucracy.

The debate over healthcare spins furiously but goes nowhere. On no other issue is so much political anger unleashed with so little desire to effect meaningful change. We are stuck for the foreseeable future with a fabled NHS where obvious failures like the one at Furness General occur again and again because no one is really brave enough to want to learn from them.

Join us on 17 March to discuss whether anyone can save the NHS. Speakers include Andy Burnham, shadow secretary of health. This event has been organised by The Spectator in collaboration with Pfizer. More information can be found here.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in