John Aubrey investigated everything from the workings of the brain, the causation of winds and the origins of Stonehenge to how to cure the fungal infection thrush by jamming a live frog into a child’s mouth (you hold it there until it — the frog — suffocates, then replace it with a fresh frog).

He seemed half-cracked as often as not to less empirical 17th-century contemporaries, and for most of the next 200 years posterity forgot him. His astonishing renaissance in the last century owed much to two novelists: Anthony Powell, who published a biography, followed by a selection of Aubrey’s Brief Lives in 1949, and John Fowles, who brought out his Monumenta Britannica for the first time in 1980. By this time Aubrey had captivated the public on both sides of the Atlantic on stage and screen in a magical performance by Roy Dotrice, who played him as a quavery old codger, doddering about in an interior as chaotically crowded as his own mind.

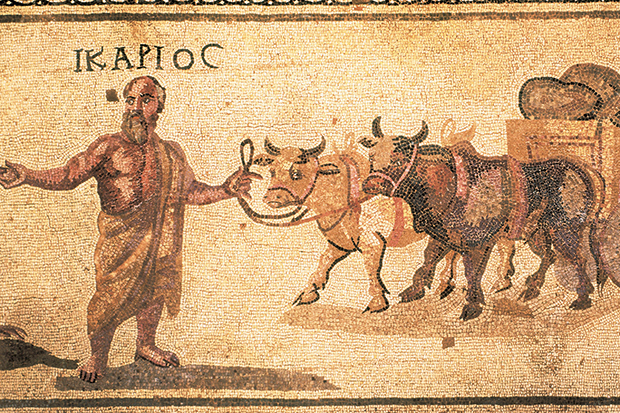

Aubrey exemplified an age of exuberant experiment and scientific expansion. The epitaph he would have liked carved on his gravestone if he’d had one (he was eventually buried in Oxford as a nameless stranger) was Fellow of the Royal Society. Fellows, who met every Wednesday, included John Evelyn, Samuel Pepys, Aubrey’s lifelong friend Thomas Hobbes, his drinking companion Robert Hooke (‘the greatest mechanic alive in the world today’), and a bright young astronomer called Edmund Halley. The aim was to swap ideas, showcase the latest discoveries and watch the modern world take shape.

Aubrey noted down everything. Spectacles were beginning to be common in England. The novel concept of gardening for pleasure rather than for strictly practical purposes caught on fast in his lifetime. Hooke was busy designing a pocket watch and a prototype flying machine. Their friend Francis Potter worked on new kinds of clock, compass and crossbow as well as blood transfusion and bee-keeping (‘He showed me bees’ thighs under a microscope’). Like others of his sort to this day, Aubrey sat up till all hours making merry at the World’s End pub ‘on my Knightsbridge rounds by moonlight’.

His thoughts and reactions are often so like ours that it comes as a shock to find that most people he knew could and did speak Latin, read by candlelight and had to dash outside to check the time on a sundial. He recognised the spread of London’s first coffee shops as a key democratic advance, an early equivalent of the internet, giving previously unimaginable access to everyone who wanted to make contact and keep in touch with a strange, fast-changing, often unsettling new era. ‘Before they opened, men only knew how to be acquainted with their own relations or societies. They were afraid, and stared at all who were not of their own communities.’

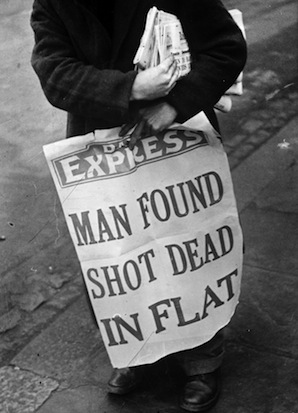

Aubrey was himself a pioneer archaeologist, ecologist, conservationist and above all biographer. Truth was the test he applied to all he did: ‘the plain and naked truth’, sometimes so raw in his writing that he needed an editor ‘to sew on some fig-leaves, to make a castration…’. No one knew better than Aubrey how little reality humankind can bear. But he also knew that his frankness, coupled with his equally obdurate insistence on recording ‘the tiny details that shape lives’, made his mini-biographies unique —and invaluable — even though they might not be fit to print in his lifetime, or indeed for long afterwards.

He started in 1680, the year after Hobbes died, by keeping a promise to his old friend to write his life. After that he couldn’t stop. By the end of March he had drawn up a list of 55 further subjects, and completed ten of them. Two months later he’d done 66. When he died in 1697 he left more than 500 of these miniatures, a gallery of his contemporaries without parallel or precedent in English. Their vitality, humanity and penetration laid down patterns British biographers have followed ever since.

Ruth Scurr by her own account aims to outdo standard biographical procedure by constructing her book directly from Aubrey’s published and unpublished texts, cobbled together (with copious additions ghosted by Scurr) in the form of a first-person diary. She does not attempt Aubrey’s concision (he could jot down the salient points of a life in half a page at a pinch: My Own Life comes in at 518 pages). For anyone already familiar with his writing, she eliminates much of his inimitable flavour by smoothing out irregularities, modernising spelling and usage, in general imposing a conformity intrinsically alien to Aubrey.

The result is blander than the original, and decidedly more prosaic, if easier to read. Aubrey used words with characteristic relish at a time when the English language was still being wrenched into something like its current shape. His work retains a faint residual resonance of an earlier age as in, for instance, the story of the apparition said to have been seen near Cirencester in 1670. Asked to explain itself, it ‘returned no answer but disappeared with a curious Perfume and most melodious Twang. Mr W. Lilly believes it was a Farie.’ This kind of jolt brings today’s reader slap up against a world that in Aubrey’s day still included phenomena as incontrovertible to the medieval mind as ghosts and fairies. The mysterious poetry of his punchline is toned down in Scurr’s relatively flat transcription —‘My friend Mr William Lilly believes it was a fairy’ — and constant slight adjustments like this one produce a cumulative blunting or blurring effect.

But even diehard Aubrey fans will find ample compensation in Scurr, especially in the richness and range of her sources. Passionately interested in everything and everyone but himself, Aubrey was incapable of self-analysis and allergic to self-advertisement. He loved clarity and order, but was quite unable to impose either on researches jotted down as he said ‘tumultuarily’, as if he were emptying out a great sack. Scurr’s scrupulous, systematic and chronological approach gives a continuity and coherence that always eluded the author.

It also yields insights not necessarily apparent from reading him piecemeal. Aubrey belonged to a 17th-century generation possessed by the rage to explore, examine and explain. Books were the only available means of recording and retaining the results, and the twin themes that emerge movingly from My Own Life both revolve around books. Aubrey had responded unreservedly to the intellectual world he first glimpsed as a 16-year-old at Oxford, a place that came to embody for him a largely unattainable dream of peace and security. Books remained ever after a prized possession to be acquired slowly and deliberately, perused with attention, preserved with care and passed on to a person, or preferably an institution, that could keep them safe.

This last was crucial because books were as precarious as they were precious. Aubrey’s passionate attachment was shadowed by an equally powerful dread implanted in him before he was ten by his grandfather’s account of the dissolution of the monasteries. The child’s imagination took hold — and never afterwards let go — of a nightmare vision of great libraries and centres of learning all over the country forcibly dismantled with their occupants turned out onto the roads, and their dismembered manuscripts flying through the air like butterflies.

The prospect of loss, destruction and dispersal, real enough in the civil war that repeatedly disrupted his Oxford education, was rarely absent for long as England’s hopes of stability advanced and receded in the ominous, often violent, always uncertain transitions that followed. Pursued on a personal level by debts, duns and lawsuits, Aubrey lost in rapid succession his family home, his income and his chances of marriage as well as his manservant and even his horse, ending up a penniless itinerant surviving in his fifties and sixties on other people’s charity.

Through it all books gave him deep and constant anxiety. Worse than deliberate banning and burning was their incidental destruction, often by rapacious cooks and barmen who commonly lined pie dishes and bunged up beer barrels with ancient manuscripts. The figure who emerges from this book is far from the nostalgic and bumbling but lovable eccentric of popular myth. Scurr’s Aubrey is formidably strong-willed, clear-sighted and firmly focused on the present and the future. Or, as he says himself on the last page, ‘I have rescued what I could of the past from the teeth of time.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in