Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita was a box-office triumph in Italy in 1960. It made $1.5 million at the box office in three months — more than Gone With the Wind had. ‘It was the making of me,’ said Fellini. It was also the making of Marcello Mastroianni as the screen idol with a curiously impotent sex appeal. No other film captured so memorably the flashbulb glitz of Italy’s postwar ‘economic miracle’ and its consumer boom of Fiat 500s and Gaggia espresso machines. Unsurprisingly, the Vatican objected to the scene where Mastroianni makes love to the Swedish diva Anita Ekberg (who died earlier this year at the age of 83) in the waters of the Trevi fountain. Sixties Rome became a fantasy of the erotic ‘sweet life’ thanks in part to that scene.

After La Dolce Vita, Fellini found himself at a creative loss and hung a sign above his desk: ‘NOW WHAT?’ Sophia Loren’s movie-mogul husband, Carlo Ponti, persuaded him to contribute to Boccaccio ’70, a collection of lewd short films inspired by the medieval Decameron, but it was a critical failure. At the end of 1961, still in ‘creative limbo’, Fellini began work on 8½, his eighth and a half film; it was to be a signpost in his development as a magician-director.

Again, Mastroianni was the lead actor, but 8½ is a very different film from La Dolce Vita. In gleeful narrative disarray, it returns to British cinemas this month in a version restored from the original negatives. Watching it the other day at the BFI, I felt I might levitate out of my seat as the movie scissors giddily backwards and forwards in time, with dreamlike sequences from Fellini’s Rimini childhood morphing into stylised fantasy sequences from 1940s Hollywood.

Daringly, Fellini disavowed the gritty actuality of Italian neorealism (Bicycle Thieves; Rome, Open City) to conjure what he called an ‘intoxicating, lucid dreaminess’. In the unforgettable opening sequence, Mastroianni floats up into the sky above an exhaust-filled traffic jam before he plummets Icarus-like down towards a beach. The implied sexual anxiety of the flying dream is a motif throughout the film.

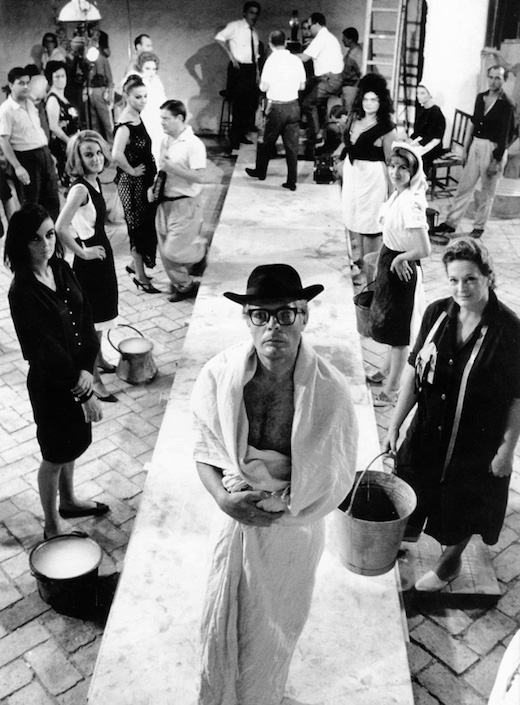

On one level, 8½ is a film about film-making. Mastroianni, in the role of the successful movie director Guido Anselmi, contemplates a costly science-fiction film about a rocket ship’s ascent from earth following a thermonuclear disaster. The project appears to be stymied, however, and now Anselmi has liver troubles. A casualty of the ‘sweet life’, he has retired to a fashionable spa town in Tuscany to take stock and reflect on his domestic and artistic difficulties. In his black suit and wide-brimmed black hat he is dressed very much as Fellini was in those years and is clearly intended to be the director’s cinematic alter ego.

While Anselmi struggles with his script, his mistress Carla arrives amid a swirl of film assistants, executive producers, costume designers and hangers-on. They importune Anselmi to push on with his film, but he wants only to sleep. Played by Sandra Milo (‘the Italian Judy Holliday’), his mistress Carla is a cheerfully vulgar and buxom woman; Fellini had ordered Milo to put on five kilos for the film. ‘I feel like a Strasbourg goose,’ she complained, but she got her revenge 20 years later when her autobiographical novel Caro Federico (1982) portrayed Fellini as a bed-hopping roué. (Fellini claimed he never read the book. ‘I don’t even want to smell it.’) Among the film’s bewildering array of other characters is the playboy producer Mario Mezzabotta and his alarmingly feral girlfriend Gloria Morin, stylised versions of Ponti and Loren.

Trouble brews for Anselmi when his long-suffering wife Luisa (played by the gamine Anouk Aimée) turns up for the day to pour scorn on his marital infidelities. (‘No affairs since you left? Poor Guido,’ she taunts.) To top it all, an annoying French intellectual berates Anselmi for his ‘squalid catalogue of mistakes’ as a director. Only in the dream world is there a reprieve from the carping. In the film’s most intoxicating flashback, the boy Guido is bathed by his grandmother in a huge wine vat and then carried to bed in soft warm blankets. Fellini’s camerawork is endlessly beguiling and fluid here. Elsewhere, a voluptuous vixen dances a carnal rhumba on a seashore in front of a group of excited schoolboys, until priests arrive to break up the impropriety. Critics speculated that Fellini himself was eight and a half — otto e mezzo — at the time of his first sexual experience.

At the time, the film’s modernist self-reflexivity was compared to Luigi Pirandello’s ground-breaking 1921 play Six Characters in Search of an Author. Pirandellian reflections on the role of art and illusion in life certainly intrigued Fellini. In the year of the film’s release, 1963, a group of avant-garde Italian writers and critics (among them a young Umberto Eco) founded the Gruppo 63 movement, which aimed to reject ‘conservatism’ in the arts and champion the subversive theatricalities of Pirandello, Proust, James Joyce and others. Yet Fellini was conspicuous among modernists for his refusal to be glum (still less prolix, pedantic or patronising). As well as being funny, 8½ is an affecting meditation on marital relations and love.

In the justly famous finale, Mastroianni calls up everyone who has appeared earlier in 8½ and, like a circus ringmaster, directs them through a loudhailer. Eighty smiling and contentedly chatting characters pour down the staircase of the spaceship’s giant launch pad towards him. (The science-fiction set was said to have been inspired by Bruegel’s The Tower of Babel.) Nino Rota’s swirling big-top score affirms the sense of a closing circus procession and reconciliation. At last, Anselmi has found the strength to undertake his film project. For all its surface frivolity, 8½ is one of the great cinematic expressions of artistic achievement in the face of feared impotence, and it remains a favourite with directors such as Wes Anderson and Jonathan Glazer.

Not everyone in Italy liked 8½ on its release. The novelist Dino Buzzati (‘the Italian Kafka’) spoke of the self-indulgent ‘masturbation of a genius’. Meanwhile Fellini, a master yarn-spinner, did his best to obscure the circumstances of the film’s birth. When journalists complained that he gave wildly different versions of its inception, he protested, ‘What’s wrong with that? All of you got an exclusive story.’

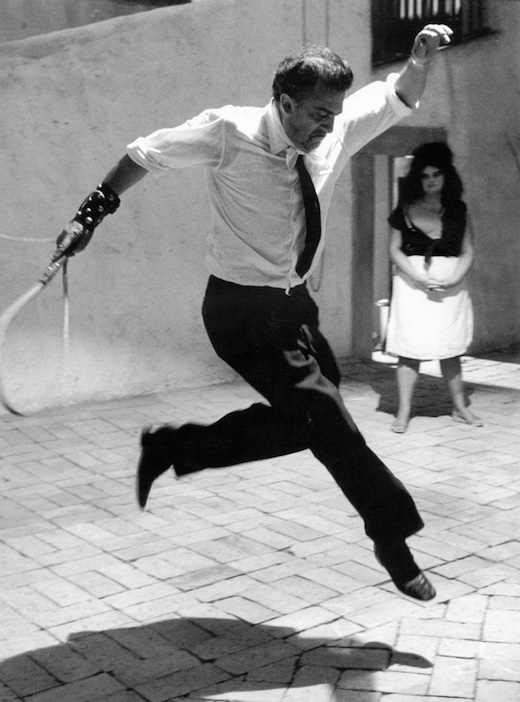

Laurence Olivier was considered for the part of Guido Anselmi, but Fellini feared that the English actor would make a hash of the gloriously comic harem scene, where the director brings all the women in his life to heel with the aid of a whip. (Among the women is a sexily deep-voiced Danish air hostess.) Mastroianni, Italy’s highest-paid heart-throb, acts the harem boss with his accustomed humour and amused self-deprecation. Of course the women pander to his every childish desire. Nothing was ever done in half measures in Fellini’s Italy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

8½ opens in selected cinemas UK-wide on 1 May.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in