With summer on its way, thoughts turn south to olive groves and manicured vineyards, to the warm water and hot beaches of the Mediterranean. But this sea that is a place of rest and beauty for some of us is the scene of drama and often despair for many others, among them people trying to cross from North Africa. So which is it, a place of calm and beauty, of refinement and culture, or one of drama and much tragedy, buffeted by the consequences of geo-political shifts?

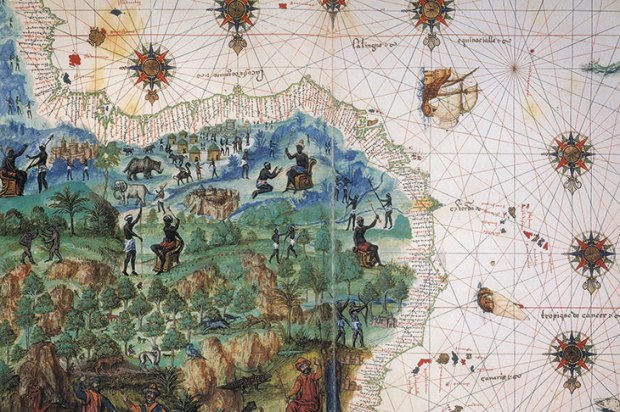

The Mediterranean has long been used to reconciling opposites, as two new books make abundantly clear. To ancient Greeks and Romans, the Mediterranean and its neighbouring seas was literally the ‘middle earth’, the centre from which everything radiated. Jump forward 1,000 years from the end of the Pax Romana to Habsburg-led Christendom and the sea was a barrier between the long-established, civilised lands of Europe and the newly emergent empire of the Ottoman Turks. Both sides had charismatic rulers — Charles V and Suleiman the Magnificent — and there was no shortage of flamboyant ‘players’, none more so than the Greek-born Hayreddin Pasha, known as Barbarossa, who was the scourge of Christian shipping while he and his Barbary corsairs were based in Algiers, but was eventually put in command of the imperial Ottoman fleet. This extended Ottoman and Habsburg confrontation across the Mediterranean has been well covered recently by Barnaby Rogerson and Roger Cowley. Noel Malcolm has not attempted another general history; instead he has found a way to approach this ongoing conflict between East and West, between Christian and Muslim, in an original and revealing way.

Forget the book’s sensational subtitle. Yes, there are knights and corsairs, Jesuits and plenty of spies, but this is micro-history and the focus of Malcolm’s story is two, related Venetian families — the Bruni and the Bruti — whose interests spread along the Adriatic and some of whose members settled south of Dubrovnic in Ulcinj, now in Montenegro.

Ulcinj was on the frontier of the Ottoman and Venetian empires and was a fluid, confusing town where one was as likely to be addressed in Albanian or Greek as Turkish or Italian. Such places are fascinating for historians because of what they can reveal about political trends, about the spread of religion and culture, the build-up of events. But they can also be frustrating: away from the centres of power, there is less chance of finding extensive or significant archives. Which explains Malcolm’s excitement when he came across a mention of a 16th-century treatise about Albania, ‘the first ever work of its kind to be named by an Albanian author’. But that was 20 years ago and it was only recently that he finally tracked down a copy of the treatise, in the Vatican library.

The story of the Brunis and Brutis has taken more than the discovery in a manuscript to unravel, because having identified that first Bruni — Antonio — Malcolm then realised that he also needed to trace the activities of Antonio’s relatives. Here the subtitle comes into play, for they were a diverse group. Through their stories, he has been able to shape a detailed set of personal narratives that span the middle sea and the second half of the 16th century. Some of these characters are more interesting and important than others; but overall they provide a fascinating focus and on both sides of the Ottoman-Habsburg divide, for the Brunis counted Sinan Pasha, a distant relative by marriage, as part of their family.

Of greatest interest are Antonio Bruni — the one whose manuscript initially inspired the writing of this book — a naval commander and spy, his cousin Giovanni, archbishop of Ulcinj, who had been a prominent participant at the Council of Trent but was captured and enslaved in an Ottoman raid, and Giovanni’s brother Gasparo, a Knight of Malta. Gasparo was commander of a papal galley in the climactic battle of Lepanto, when the Christian Holy League defeated the Ottoman fleet. (The novelist Miguel de Cervantes was also present, aboard a Genoese galley.) Malcolm, in an inspired piece of deduction, places Giovanni on an Ottoman galley, tied to an oar and within sight of his brother.

The Lepanto scene is one of many that makes Agents of Empire such an extraordinarily rich book. A significant work of scholarship, as one might expect from a former foreign editor of this publication and a fellow of All Souls, Oxford, it is dense and sometimes frustratingly both held back by detail and pushed on by supposition. But the author’s extensive digging has uncovered much new material, and his obsessive enthusiasm for the story of these families makes for a compelling and unexpectedly entertaining book.

Conflict did not end at Lepanto, as Malcolm makes abundantly clear. Jump forward to the early 17th century — and to the Mediterranean seen through the eyes of the antiquarian and lawyer Nicolas Fabri de Peiresc — and the sea is as divided as ever. And as united. Unlike the Bruni and Bruti, Peiresc did not spread himself or his family along the shores. He remained in Provence, where he was born and died and where his extensive archive, some 70,000 documents, remains. But he was a man of letters in the most literal sense and his pages of words criss-crossed the water. There is a wealth of fascinating material here, enough to justify Peter N. Miller producing another volume from the Peiresc archive to add to the ones on the Levant, Provence and Europe.

Peiresc was a polymath savant and his interests and activities extended from understanding antiquity to writing about Algerians in Marseille, to scraping coral off the seabed. He stirred his colleagues and correspondents around the Mediterranean to observe the lunar eclipse of 1635, and then to help create an accurate map of the sea on which they all depended, by testing scientific theory against the experiences of sea captains (who were agreed that the accepted distance from Marseille to Alexandretta was exaggerated by perhaps 500 miles). I was reminded of Joseph Banks, over a century later, who also used his energy, position and wealth to advance science and add to the sum of human knowledge.

All this is fascinating and, as with the Bruni, reveals much of interest about the Mediterranean. Miller, like Malcolm, has done exhaustive research, as more than 200 pages of references and other end-matter suggest. But although his book has a tighter focus, it lacks coherence. He talks of wanting ‘to reproduce the sense of gaps’ in a life and ‘the historian’s sense of disorientation’.

This, and other academic flourishes might work in the lecture hall, but they do not sit well alongside Miller’s claim that we know more about Peiresc than any other scholar of his age and they make for a frustrating book. Miller is correct in describing Peiresc as ‘the first person to see the Mediterranean as a world to be studied and reflected on, not merely lived in’. At a time when the Mediterranean is becoming increasingly important to us, whether because we care about the plight of people drowning in it, worry about possible threats from the opposite shores or where we are going to go this summer, the views of this central sea to be found in the work of Peiresc and the story of the Brunis are too interesting to ignore.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

'Agents of Empire: Knights, Corsairs, Jesuits and Spies in the Sixteenth-Century Mediterranean World', £24 and 'Peiresc’s Mediterranean World', £26.95 are available from the Spectator Bookshop, Tel: 08430 600033. Anthony Sattin is the author of The Young Lawrence, A Winter on the Nile, The Gates of Africa and Lifting the Veil.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in