One morning in March 1921 a large man in an overcoat left his house in Charlottenburg, Berlin, to take a walk in the Tiergarten. A young man crossed his path, drew a pistol and shot him in the neck. Emitting a groan ‘like a branch falling off a tree’, he fell dead. The assassin ran, but was arrested by the crowd. ‘What do you want?’ he asked. ‘I am Armenian, he is Turkish. What is it to you?’

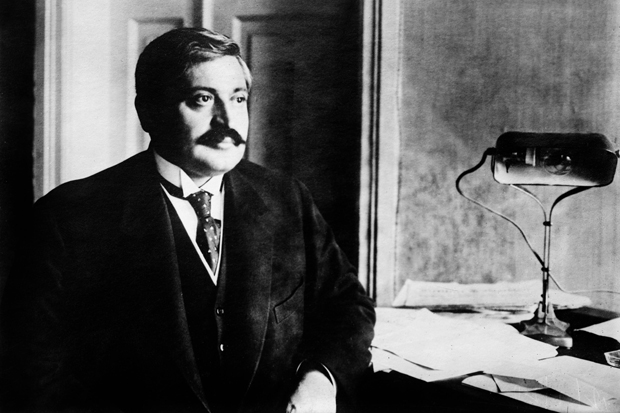

The victim was Talat Pasha, erstwhile interior minister of the Ottoman empire and convicted war criminal. His nemesis was Soghoman Tehlirian, engineering student and agent of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. Talat topped the ARF’s list of targets: revenge for the genocide of some 1.5 million Armenians between 1915 and 1917. Like Israel’s abduction and trial of Adolf Eichmann, the ARF mixed vengeance with the ‘propaganda of the deed’. To serve justice, the victims broke the law. The ensuing trial would enter the historical record; the sentence would be the world’s memory.

Tehlirian was a Dostoevskian martyr: epileptic, chastely passionate about his girlfriend, the beautiful Anahid, haunted by nightmares of his decapitated mother, and devoted to killing. Serving in a Russian-trained Armenian unit, he had witnessed the aftermath of the genocide and learnt that his mother and brothers had been murdered, his sisters raped. After the war, he assassinated an Armenian traitor in Constantinople on his own initiative. In early 1919, the ARF recruited him, and sent him to Watertown, Massachusetts, where Armenian Americans were funding and planning their revenge. They told him not to flee after shooting Talat, and primed him for his trial.

In court, Tehlirian perjured himself, to save his life, protect the conspiracy and publicise the genocide. He testified that he had witnessed his family’s murders, and had escaped from a pile of corpses. Although he had worked with a team, he claimed to have acted alone, after encountering Talat by chance. The judge did not ask how Tehlirian had entered Germany on a Persian passport, bearing a Swiss student visa and a large amount of money; perhaps, Eric Bogosian suggests, because Germany, as Turkey’s ally, had been complicit in the genocide. Bogosian also posits that Aubrey Herbert, Evelyn Waugh’s father-in-law, and the inspiration for Sandy Arbuthnot in John Buchan’s Greenmantle, may have informed the ARF where Talat was hiding.

Testimonies from Armenian survivors convinced the jury that Tehlirian had served justice upon Talat; and a doctor confirmed that Tehlirian was not responsible for his behaviour. In June 1921 he was acquitted. Meanwhile, ARF agents hunted down their enemies in various scenic locations. In occupied Constantinople, the Azerbaijani minister Khan Javanshir was shot on the steps of the Pera Palace hotel. His assassin used Tehlirian’s defence before a British tribunal, and was acquitted.

In Rome, the former prime minister Said Halim Pasha was shot between the eyes as he climbed down from his carriage. His assassin escaped, as did the accomplice who collected his coat and hat. In Berlin, Bahaeddin Shakir, the leader of the brutal Special Organisation, and Cemal Azmi, the ‘Butcher of Trabzon’, were shot as they took an after-dinner stroll.The killers vanished into the crowd. Cemal Pasha, supervisor of the ‘relocation’ of Armenians into the Syrian desert, died outside the Cheka headquarters in Tbilisi. His killer was caught, and died in the gulag. Armenians working for the Soviet Cheka killed the ex-war minister Enver Pasha before the ARF could get to him.

In late 1922, the ARF suspended Operation Nemesis. The western powers were warming to Ataturk’s republic. Sooner or later, the plot would come to light and the new Armenian republic, under Soviet control and flooded with refugees, had enough problems. The world’s amnesia about the ‘great catastrophe’ was beginning. Tehlirian changed his name and married his Anahid. They settled in Valjevo, Serbia, where Tehlirian practised his marksmanship at the town’s gun club. He had found, Bogosian writes, ‘a kind of resolution’ — but not peace. After 1945, Turkish agents tracked him down. He moved to Morocco, and then San Francisco.

Eric Bogosian is an Armenian American playwright and actor. His telling is dramatic and candidly partial, and the skullduggery of his stake-outs, courtroom scenes and shootings is vivid and tense. He compares his story to a film script — and Operation Nemesis reads like a pitch. It should be filmed: as Steven Spielberg showed in Munich, dramatisation brings out the ambiguities of revenge.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.50 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in