True Story is based on the book True Story, which is itself based on a true story, so there is a lot of truth knocking about, I guess you could say, but absolutely none of it is at all interesting. It sounds as if it will be fascinating, as it’s about the disgraced New York Times reporter Mike Finkel’s relationship with Christian Longo, a man accused of murdering his wife and three children, but it goes absolutely nowhere. At one stage someone says to Finkel about Longo, ‘He doesn’t deserve to have his story told,’ to which Finkel replies, ‘Everyone deserves to have their story told,’ to which I would have said, had I been asked, ‘None of you deserves to have your story told. Now, all of you, go away and behave.’

This is a first film directed by Rupert Goold, the highly acclaimed British theatre director, but it shows surprisingly scant visual flair, as it relies too heavily on redundant flashbacks that add nothing to the story, and redundant scenes — why, as one character was typing at his laptop, was another shown playing the piano? It kicks off with a teddy falling in slo-mo to signify children have been slain (if it’s not a teddy, it is usually a doll). But rather than capturing a falling teddy — or a doll, had it been a doll — someone on this film might have better asked, ‘What’s in this for the audience? Why are we making this? Why, why, why?’

It opens while Finkel (Jonah Hill) is still at the New York Times. He is one of their star magazine writers. ‘You’ve had nine covers in three years,’ says his girlfriend Jill (Felicity Jones) admiringly, although my first thought was, ‘They hardly overwork them there. I’m off!’ However, once his feature on the slave trade in Africa is discovered to be, at least in part, an Untrue Story, he’s sacked. ‘You have a great future ahead of you, Mike,’ says the editor, ‘but it isn’t here.’ The script is riddled with such clichés. I think someone even says, ‘But you can never escape who you are.’ (Aside from anything else, this is decidedly false. After two bottles of wine, for example, I find I can escape who I am quite nicely.)

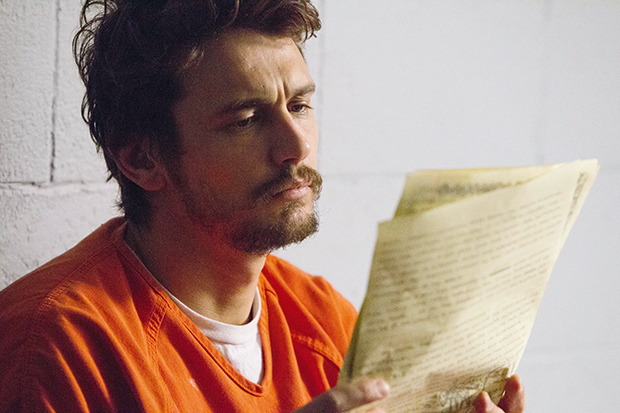

Finkel retreats to his home in Montana, which he shares with Jill, who is supportive and dull (a completely thankless role for Jones, who has to play the piano while he types), and where his magazine covers hang framed on the wall. Are we meant to like Finkel? Probably, but this offers no reason to do so. (Earlier, when asked why he thought he was being summoned to the editor’s office, he’d quipped, ‘I have a hunch it rhymes with schmulitzer’ at which point I had a hunch he was a schmickhead, and nothing would later contradict this.) He struggles for work, with even GQ turning him down, so it must be bad, but then he discovers that a man wanted for killing his family back in Oregon has been picked up in Mexico, and has been hiding out using Finkel’s name. Finkel is on it like a shot. Finkel, being a schmickhead, sees it as his In Cold Blood. (We’re not told this specifically, but I did get that impression.) He makes contact with Longo (James Franco) and visits him in prison, with the conversations becoming the book, and now this film.

I was, I confess, expecting one of those gripping pas-de-deux films, with the power going back and forth, but all this amounts to is two charmless, boring men sitting across the table from each other being charmless and boring (as played charmlessly and boringly by Hill and Franco, neither of whom brings any depth). There is no suspense — Longo’s guilt is never seriously in doubt — and no cat-and-mouse psychological games, as no one character reveals anything that forces the other to play catch-up. This is, in fact, steadfastly unrevealing all round. There isn’t any exploration of why Longo did what he did — even if he’s insane, he must have explained it to himself in some way — and no exploration of his background. We’re not even properly told what drew Longo to Finkel in the first instance. As to the film attempting to draw a moral equivalence between the two — ‘We’re not so different,’ Longo tells Finkel — I see quite a big difference between lying and the slaughtering of your entire family, but maybe that’s just me?

It all builds to a final court scene during which the children’s injuries are graphically detailed, which would have been OK had you felt that the film had earned it; had it expanded our understanding in some way, or said something of value about the importance of truth. But without that it felt exploitative — these are real children, remember? — and hateful. Everyone deserves to have their story told? No. Emphatically not.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in