When is a rape not a rape? It’s an unsettling question — far more so than anything offered up by the current headline-grabbing William Tell at the Royal Opera House — and one that lies beneath the meticulous dramatic archaeology of Fiona Shaw’s The Rape of Lucretia. Unlike William Tell, however, there seems little chance of this attack starting riots. Where the director of Tell asserts, Shaw interrogates — a delicate, insistent questioning that probes further and more intrusively, a violation of ideological rather than physical absolutes.

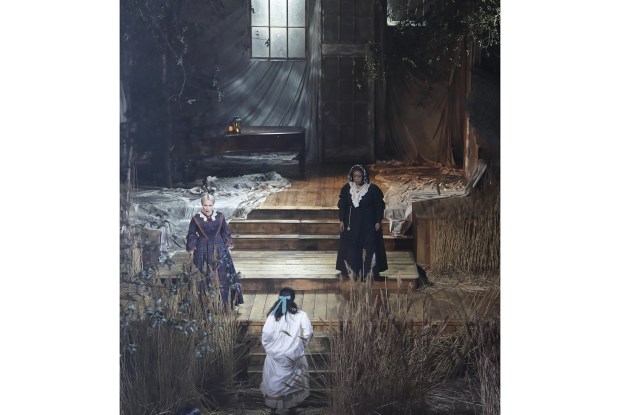

Debuted in 2013 as part of the company’s touring season, Shaw’s production now returns to the main festival, where the chamber opera had its première in 1946. Excavating the tale of Lucretia from under the black earth of Michael Levine’s austerely beautiful set, the Male and Female Chorus also look back to the circumstances of the opera’s own composition. Dressed in the drab clothes of recent wartime, they remind us that Rome’s abuse at the hands of the invader-Etruscans could so easily have been their — and our — own, that this rape is one of nation-state as much as of individual.

Ronald Duncan’s libretto frames its classical story with a post-Christian morality, fussily swathing it in a modesty-cloth of sanctimony that risks obscuring the fleshy interest beneath. It’s a problem for any director, and one Shaw tackles aggressively. Religion is the alpha and omega here, from the opening tableau of the male body entombed in earth to the closing image of the crucified Christ, but as to whether it can heal, solve, or merely console is left bleakly uncertain.

Britten’s instruction that his two Chorus figures ‘comment upon the action but do not take part in it’ is defied by the passionate interventions Shaw demands of them. In her hands, this man and woman (Allan Clayton and Kate Royal) struggle against their own impotence, desperate to pre-empt, to undo a tragedy already long-since sealed. It’s a decision that rewrites the emotional architecture of the piece, supplementing the humanity of Lucretia with echoes and responses that question the sufficiency of religion’s comfort. It’s a strategy that relies absolutely upon the skill of its cast.

Reprising his 2013 role, Clayton is still urgent, disquieting, miles from Pears’s or Bostridge’s otherworldly coolness. If Royal lacks the instinctual warmth of her predecessor Kate Valentine, it’s an awkwardness that plays tellingly against Christine Rice’s fervent Lucretia. Reduced from playful sensuality to a self-loathing that turns song into guttural moans, her Lucretia is as disturbing a creature as this singing-actress has ever created. An ecstatic Lucia from Louise Alder and a bluffly resonant Collatinus from Matthew Rose both catch the ear, but it’s the chamber group from the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Leo Hussain, who take an unspeakable act and give it most eloquent and allusive voice.

Shaw’s world of moral shadows couldn’t be further from the certainties of Robert Carsen’s Falstaff. Glossy with wit and high on its own charms at its first outing in 2012, the show’s first revival reveals that service at the Merrie England Country House Hotel is as slick as ever.

It’s hard to resist the giddy energy of Carsen’s 1950s staging. Paul Steinberg’s designs (long on hunting prints and panelled interiors) set the tone for Shakespeare sitcom-style, with a pastel-coloured cast romping their way through Verdi’s deft dramatic set pieces, and only a laughter track missing to complete the effect. Memorable stage pictures — room-service trolleys strewn corpse-like across the gastronomic battlefield of Sir John’s hotel room, Alice’s apricot and avocado fantasy of a kitchen — jostle for attention, but none can steal the spotlight from Ambrogio Maestri’s Falstaff: an all-you-can-eat-buffet of a figure, whose dramatic generosity constantly threatens to tip over into excess. Raw Italian power is spiced with twinkling mischief for an anti-hero who’s definitely more Signor than Sir John.

Anna Devin’s Nannetta — silvery-sweet and impeccably sung — is the stand-out in a strong revival cast that also features a glamorous Alice from Ainhoa Arteta and a superb Ford from Roland Wood, offering all the vocal beauty Maestri’s wide-load voice cannot. Ensembles court (but reliably avoid) danger thanks to thrilling pace and drive from Michael Schonwandt’s pit. Only Agnes Zwierko’s Mistress Quickly disappoints, dwarfed by memories of 2012’s larger-than-life Marie-Nicole Lemieux.

Yet, for all its slapstick and sunshine, Verdi’s Falstaff is no farce. The bluff retainer and loyal companion of Henry IV cannot be entirely lost behind the bloated, bibulous knight of The Merry Wives if the delicate tragedy that sits so close to the opera’s colourful surface is not to disappear. Carsen’s Falstaff is an opera buffa whose drama (if not its sophisticated score) could belong to any Donizetti or Rossini. Verdi’s Falstaff, by contrast, is something rather more complicated, a commedia lirica that needs the sting of pathos and the salt of tears to balance its sweetness.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in