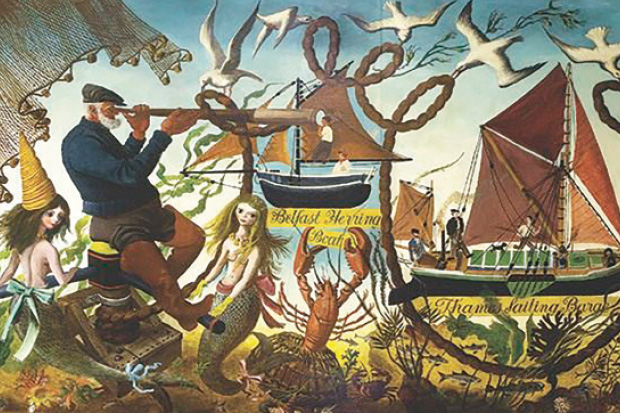

Most current writers on railways don’t want to appear at all romantic lest they be shunted into the ‘trainspotter’ siding. But Michael Williams is unafraid to state the obvious fact about Britain’s railways, which is that they were far more attractive in the past:

It is sometimes tempting to wonder if, deep in every railway operations HQ, there is a department whose sole job is to think up ways of corroding the experience of passengers. Here are seats that don’t line up with windows, garish plasticky train interiors, an incomprehensible fares system, a cacophony of endless announcements….

In The Trains Now Departed Williams celebrates ‘the best of what is gone from our railways’ in 16 vivid, highly readable chapters. One concerns Verney Junction, formerly the furthest outpost of the Metropolitan Railway. Nominally part of London Underground, Verney was located — as Williams puts it — ‘in a field’ in rural Bucks. In Edwardian days, the Met used to send luxury Pullman carriages with green silk blinds and ormolu baggage racks between Verney and the City, and Williams imagines himself leaving Farringdon after a day’s work, and being asked by a white-jacketed attendant, ‘Touch more angostura in your gin, sir?’

‘Maybe,’ he writes, ‘Verney was just a dream, like Alice’s train from Through the Looking-Glass. ‘Dreamlike’ is the word for many of Williams’s skilful evocations. Take the night ferry train that, from 1936 to 1980, ran from Victoria to what was then known as ‘the Continent’. It didn’t take a sudden leap into the air, like Alice’s train, but it was loaded onto a boat every night, and there were lifejackets in all compartments.

Williams conjures up the Somerset & Dorset Railway, whose engines were Prussian blue lined out in gold, with scarlet buffer blocks, and whose staff wore ‘snazzy green corduroy’. Its metals hosted the Pines Express, whose eccentric mission was to take Mancunians to Bournemouth. Williams also gives us Blackpool Central station where holidaymakers — half a million of them in August Bank Holiday week, 1935 — were disgorged directly onto the front. ‘You could party through the night in the Tower Ballroom and still get a train home. In 1952, the final departure was at 1.55 a.m.’ The conspirators against railway charm do their work thoroughly, and they have a sick sense of humour. Accordingly, the site of Blackpool Central is now ‘one of the biggest car parks in northern England’.

Three Men and a Bradshaw takes us back to the 1870s when the burgeoning railways were allowing the lower middle classes to engage in tourism, as opposed to ‘travelling’, which had been a upper-class affair. The book is a diary of holidays taken in Jersey, Devon, Wales and Scotland by John George Freeman, a cloth merchant from London, and his two brothers, both tailors. They were Baptists, like the great promoter of tourism, Thomas Cook. They carried with them one of Mr Bradshaw’s railway handbooks — like real-life Michael Portillos. Bradshaw himself was a Quaker, and early tourism was shot through with the desire for ethical self-improvement arising from nonconformity.

And so the brothers’ idea of fun while ‘doing’ North Wales was to have a hearty breakfast before ‘sallying forth’ to view some chapels, ideally joining in the singing. They were keen singers, who learnt music by the Tonic sol-fa method. The introduction commends Freeman as reminding one of Mr Pooter in TheDiary of a Nobody. I’m not sure it’s admirable to resemble a figure of comic grotesquery, but Freeman certainly has Mr Pooter’s dodgy sense of humour (‘though it was a “mail” train, ladies were allowed to travel therein’), and his pomposity (rainfall is always ‘Jupiter Pluvius’, as in ‘Jupiter Pluvius remained briskly engaged and was having a capital innings’). He also has Pooter’s priggishness: trains mainly feature in terms of the brothers’ desire to avoid sharing compartments with smokers.

Freeman is redeemed by moments of beautifully clear-eyed observation (at Glyn Neath station he watches a porter ‘lunching off a raw onion and a piece of bread’) and by his superb, darkly comic little drawings. Having learnt from the introduction that Freeman was fated to die at a young age, I began to find great poignancy in the innocence of his pursuits. Here he is after going to see some waterfalls at Llangollen: ‘The tea set before us was soon attacked with our usual vigour, the bread and butter being especially good.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

'The Trains Now Departed', £16 and 'Three Men and a Bradshaw', £13.99 are available from the Spectator Bookshop, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in