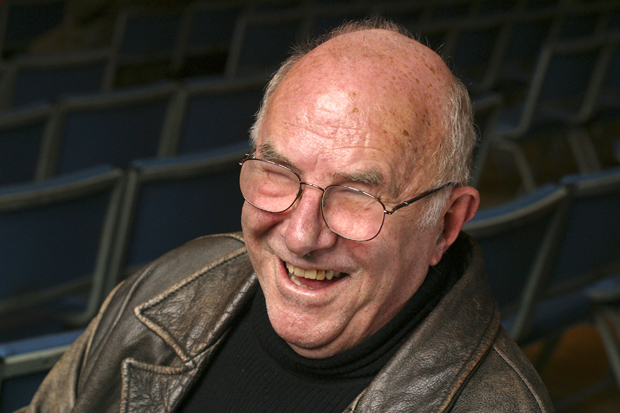

In the preface to his great collection of essays The Dyer’s Hand, W.H. Auden claimed: ‘I prefer a critic’s notebooks to his treatises.’ Auden’s criticism is like that: a passage of insights instead of a single sustained argument, and the same is true of Samuel Johnson, whose works are a pleasure to read for the feeling of the pressure of a great mind at play. Clive James belongs in this company.

His new book Latest Readings is a kind of reading diary: a collection of short essays, each prompted by one book or a handful he happens to be reading. They are not in any logical order or sequence, but are given unity by two things: one biographical, the other stylistic. James is — as has been widely publicised over the past two years — now dying, of leukaemia and emphysema, and while he only briefly mentions it here, this whole book is marked by a sense of medical struggle and imminent extinction. Olivia Manning’s cycle of novels, he writes, ‘makes now more bearable’. So the title contains a very Jamesian pun: it means both most recent and, implicitly, last. He will not be reading these books again.

He looks again at Hemingway, and Conrad, and writers he has clearly spent his lifetime with, and because this is mostly re-reading, the timeframe is a little blurred. He writes in a constant present tense (‘I have just started to read…’ and ‘I am currently under the spell of…’), and this is perhaps because of another buried pun: ‘I read’ is both the present and the past of the same verb, pronounced differently but spelled the same, as if the act had only its ever-present moment.

What kind of reader is he? A charming one: inquisitive, insightful, wry. He reads very personally (on Patrick O’Brian’s swashbuckling maritime adventures: ‘I started wondering whether I might have been a better man if I had gone to sea’). He likes books about wars and politicians, about movies and the sea; which is to say that he has masculine tastes. He is generous: both to the book in hand and also to his readers, and is polite enough to assume that we might have read almost as much as he has. As he is also Australian, a thread which connects many of his reading choices is the colonial experience, both as a subject and a master (Kipling, Naipaul; even the military volumes bear upon that particular history). He does not make this point explicitly, but he does not really need to.

Reading this collection it is hard to escape the impression that all criticism — and perhaps all reading — is an autobiographical exercise. Reading is for James a physical activity: both a pleasure (he compares reading Anthony Powell’s novels to eating ‘plates of sweets and grapes’ in the late summer sunshine) and a necessary therapy (he describes reading Kipling’s poetry while ‘ambulating’, or walking round and round his house to prevent thrombosis). Sometimes it is even treatment — he reads the Australian poet Stephen Edgar while hooked up to an IV drip — but most of all, it is simply life. On Hemingway, he writes: ‘For any writer who does not die instantly, the time of physical decline is a new subject.’ Close to the end he reveals that due to operations for cataracts, he reads with only one eye, which makes this book the record of truly noble determination.

All this might add up to a gloomy book; but it isn’t. Of one military history, he observes: ‘The text is full of observation, judgment and accurate detail, and those things are always new.’ The same might be said of this book. Or, better, in looking upon the volumes which surround him, which he has loved through his life and to which he keeps returning, he writes: ‘They are an arcadian pavilion with an infinite set of glittering, mirrored doorways to the unknown.’ Oh, and he also likes Game of Thrones.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £11.69 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in