In Marianne in Chains, his last book on Occupied France, Robert Gildea offered an original view of life in that country between 1940 and 1944, arguing that outside the cities it had not always been as bad, nor had the Vichy regime always been as reactionary, as was subsequently claimed. Confining his research to three departments in the Loire valley, Gildea also suggested that for most people most of the time the Resistance was a dangerous irrelevance, to be avoided wherever possible. These conclusions were presented at a conference in Tours where they caused a minor uproar among French specialists.

Gildea, professor of modern history at Oxford University, now turns to a much bigger subject. Fighters in the Shadows covers the whole of the wartime period and the whole of France and concludes with an analysis of the role that post-war myths have played in the history of the Occupation.

The history of the French Resistance is usually concerned with a movement inside France that was disorganised and isolated, composed of numerous mutually hostile groups struggling against the occupying forces. They were united in nothing except a determination to carry on the fight and defeat the German invaders. The main currents within this movement were the FTP — a communist network intent on starting a national insurrection — three centrist movements — Combat, the largest non-communist organisation; Libération; and Franc-Tireur — and on the right the ORA, formed by army officers who were sympathetic to Marshal Pétain, the Vichy head of state.

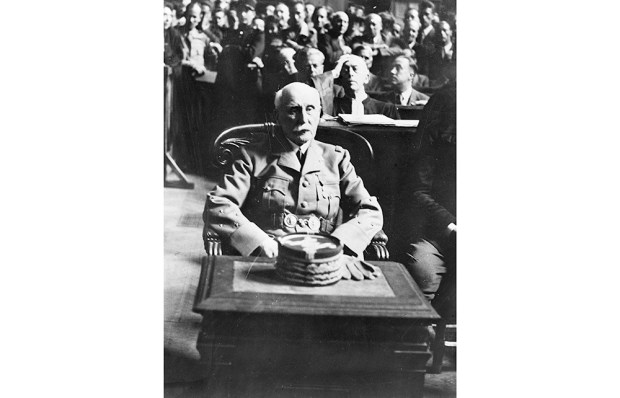

The ORA resisters accepted the armistice of 1940 but were reactivated by the German invasion of the unoccupied zone in November 1942. For the purposes of liberating France, all these groups eventually agreed to unite in support of the Allied landings. They accepted the leadership of General de Gaulle — who had succeeded in imposing a degree of authority on the ‘resistance of the interior’ through the action of his personal delegate, a retired departmental prefect called Jean Moulin.

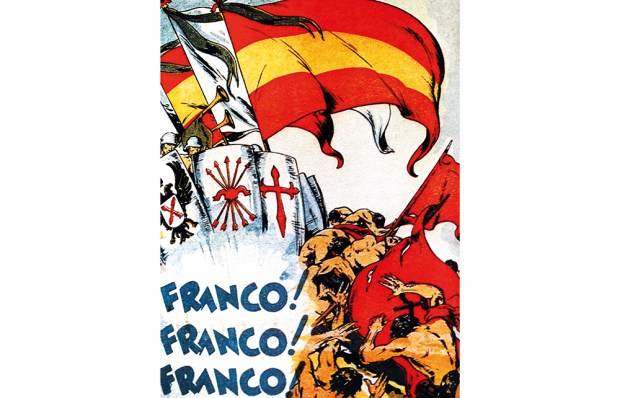

In place of this familiar picture Gildea proposes a different model. He defines Resistance as ‘refusing to accept the French bid for armistice and the German Occupation, and a willingness to do something about it that broke rules and courted risk’. This definition allows him to include in the ranks of the Resistance the ‘Free French’ in London, army officers in the French empire who rejected Vichy orders and signed up with the Allies and even the Pétainiste leaders of the ‘Army of Africa’ who changed sides in 1943 after the Allied landings on the north African coast. Among the many squabbling bands making up the ‘resisters of the interior’ — who regarded themselves as the only ‘real’ resisters — he identifies Catholic groups, German Communists, non-Communist Marxists, Spanish Republicans, other assorted foreign networks and, importantly, immigrant Jewish resistance fighters. The last were organised by the FTP into an affiliated network, the FTP-MOI, which —unlike most communist resistance organisations — took heavy casualties. In 1985 survivors of this force accused the wartime communist leadership of first allocating the most dangerous operations ‘such as attacks on German columns and German generals’ to the Jewish fighters of the FTP-MOI, and then betraying them.

Gildea rightly emphasises the importance of women in the Resistance and the way in which their role has frequently been overlooked or undervalued. Of the 1,038 holders of the Order of the Liberation, the highest Resistance honour, only six were women. Initially, women resisters were sometimes spared immediate punishment and were occasionally released or deported when they were caught, rather than being shot (though when one considers the slow death that frequently followed deportation into the Nazis’ ‘Night and Fog’, this was not much of an advantage). Women in France during the war had more immediate problems than blowing up the odd electricity pylon. In July 1940 over a million mothers became single parents overnight with 1.5 million French soldiers taken as prisoners of war. Children and elderly relations became their sole responsibility; they often faced shortages of food and fuel and none had any military training. They did not even have a vote. Nonetheless, they were frequently among the earliest volunteers.

One of the novel aspects of Gildea’s account is his decision to accord equal legitimacy (or illegitimacy) to Gaullist patriots and Communist rank-and-file resisters, even though the latter were not fighting in defence of France but were intending to use insurrection as a means of establishing a revolutionary order under the direction of Moscow. He writes of the Gaullist ‘seizure of power’ — intended to re-establish the authority of the French state — and the opposed Communist desire for national insurrection, ‘to usher in popular government and far-reaching reform’.

In a life of Jean Moulin (published in 2000 and recently reissued as Army of the Night) I suggested that the ultimate aims of the Communist resistance were so different from those of the patriotic movements that the Communists should not be regarded as part of the Resistance at all. Gildea takes this argument further. He concludes that the disparity of the component parts of the ‘resistance of the interior’ suggests that ‘it may be more accurate to talk less about “the French Resistance” than about “resistance in France”.’

The second novelty in Gildea’s approach is his use of sources. He traces the methods employed over the years by French historians to establish an official history of the wartime period. Distinguishing those who relied on documentary sources from those who preferred written and oral testimony, he writes: ‘This study is squarely based on testimony.’ He adds: ‘Only first-person accounts can lay bare individual subjectivity, the experience of resistance activity and the meaning that resisters later gave to their actions.’

One of the disadvantages of this preference for testimony is that the ‘memoirs’ of a serial fantasist like the resister Lucie Aubrac, who was once implored by her husband Raymond to ‘stop telling lies’, is here taken at face value, side by side with the verified stories of women who were tortured and shot, such as the Jewish student Jeanine Sontag, or others who suffered atrociously and nearly died for their beliefs, such as Geneviève de Gaulle, the general’s niece.

Another example of the unreliability of testimony is Gildea’s account of the first shooting (called ‘the execution’) of an unarmed German serviceman. The killing was carried out as FTP policy in Paris in August 1941, following the ending of the Nazi-Soviet pact. Gildea reproduces the assassin’s report, obtained from the archives of the (pro-Communist) Musée Nationale de la Resistance at Champigny-sur-Marne, without comment. In this Gilbert Brustlein claims that on the platform of a Métro station he and his companions ‘spotted a magnificent naval commandant (i.e. naval captain) strutting on the platform’. They shot the German in the back as he boarded a train and then ran away. Gildea adds that the killing of this ‘naval warrant officer’ had a huge impact, which is true. But the victim, contrary to Brustlein’s report, was not a naval captain or a warrant officer; he was an aspirant — a young naval cadet working as a clerk, a fact that was widely publicised at the time.

‘The story of the French Resistance,’ Gildea writes, ‘is central to French identity.’ In a brilliant Conclusion he traces the way in which the narrative of Resistance has been disputed by rival interest groups throughout the post-war period. The original Gaullist myth of 1944, that the whole of France had resisted, was succeeded by the Communist one, that the Party had provided the unchallenged leadership of the armed struggle. The inaccuracies and exaggerations in the Communist account eventually gave way to a tendency to emphasise the ‘foreign’ contribution to the battle.

This provided the remarkable spectacle in 1982 of President François Mitterrand inaugurating a statue in honour of the Spanish Republicans who had died for France. Whether those brave men and women were ‘dying for France’ is a moot point. But had they been able to attend the ceremony they might have been surprised to see that they were being honoured by a man who had spent much of his time during the Occupation blacklisting Gaullists, Communists, freemasons and other opponents of the Vichy regime.

Following a series of trials in the 1980s of wartime collaborators, the dominant narrative became one of Jewish suffering and resistance, since when both Gaullist and Communist narratives have made a comeback.

Gildea’s decision to narrow the complex politics of French Resistance down to a struggle between Gaullists and Communists provides an interesting new perspective on the liberation period. But his consistent preference for the Communist narrative over the Gaullist version is the least convincing aspect of his ‘New History of the French Resistance’. The success of the Allied military chain of command in stifling the Communist-led insurrection in the late summer of 1944 robbed France of nothing, except the same glittering post-war future that awaited the people of the German Democratic Republic. This would probably have been preceded by a horrifying civil war, as happened in Greece. Anyone who doubts this need only consult the record of the five-month reign of terror that broke out in Marseilles in September 1944, presided over by the regional commissar and Communist Raymond Aubrac.

The real story of the French resistance is that of ‘the little soldiers’ who frequently had no idea which organisation they had signed up with, and who risked their lives out of courage and sense of common humanity. Gildea provides the example of Jeanine Sontag, among others. They could also be represented by the medieval historian Marc Bloch, a member of Combat, arrested by Vichy police and shot on the orders of the Gestapo on 16 June 1944. In his ‘Last Testament’ he wrote:

I was born Jewish… I have never been tempted to deny it…I have loved and served France with all my strength…and I die as I have lived en bon Français.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.50 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in