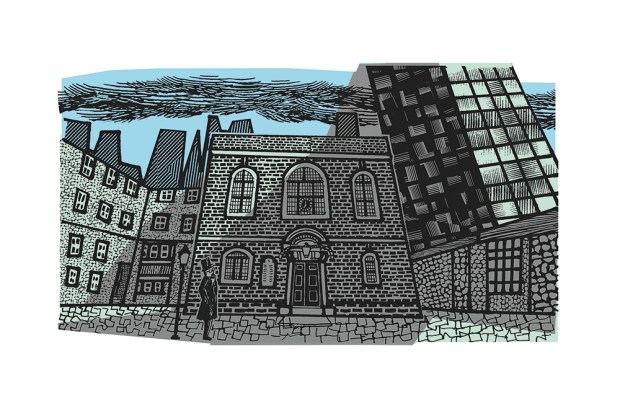

Lant Street would be easy to miss, if you weren’t looking for it. Charles Dickens lodged on Lant Street as a child, during his father’s stay in Marshalsea debtors’ prison nearby. The Gladstone Arms is about halfway down, doors open to the narrow street on a warm afternoon in August.

Inside, an old man nurses a pint in late summer light that falls through mullioned windows. The grain of the oak floors has a dark patina of London grime. There is nothing spiffed-up about the place. But it’s beautiful, and in decent nick. A black and white cat sits on the piano.

This tiny place is also a live music venue, and even has an in-house label for bands that play there regularly. CDs are for sale at the bar. The Gladstone also sells Pieminister pies, from a company based in Bristol. From about 7 p.m., even on a Monday in August, it starts filling with young ‘creatives’ and innovators: a demographic contemporary politicians wax lyrical about.

So the Gladstone Arms supports small businesses (‘the lifeblood of the economy’, according to those same politicians), employs local people, and serves the local community. And it’s thriving. Unfortunately, it now looks doomed.

Last year, the site and the pub that has stood there since the Victorian era were acquired by a holding company based in the Cayman Islands, called Sartoria. Another firm set up last year in the Isle of Man to specialise in the London residential market provides the bridging finance until a decision on the site is made. The parent company is based in Luxembourg.

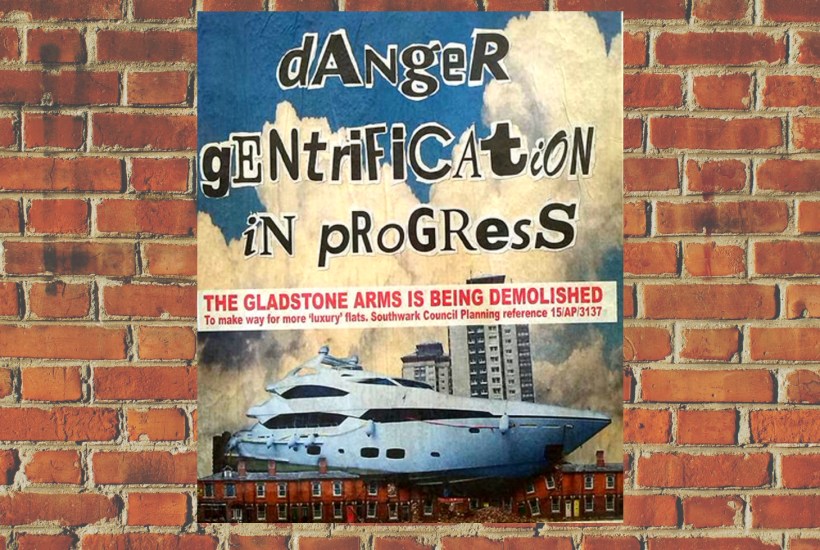

Sartoria has applied for planning permission to demolish the pub and erect a ten-storey building with nine storeys of luxury flats (‘with panoramic views’) above a brand-new pub on the ground floor. Around the corner on Marshalsea Road, where once the prison stood, a studio flat is on the market for £425,000. These new flats will sell for far more.

The economics are simple and if, as looks likely, Sartoria achieves planning permission, it will be all up with the Gladstone Arms. Of course the fate of one pub is immaterial. But 3,000 London pubs have closed in recent years. Just a stone’s throw from the Gladstone, the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, London’s most celebrated gay pub, is under threat. It has been acquired by a group of Austrian property developers, who have given no guarantees for its survival.

Some say this is a good thing, and the latest wave of foreign money is bringing prosperity, development and badly needed new flats and housing. This indeed has been the position of Boris Johnson as Mayor of London.

There is another point of view. London is now undergoing the same process of moral and physical destruction that many British cities underwent in the 1960s, when their centres were ripped out by property developers. Think of Birmingham.

The Gladstone thrives. It is at the heart of a community. Do we really want an anonymous property group, with links to the Cayman Islands, the Isle of Man and Luxembourg, to ruin it?

Chris Kendall is one of those who’s determined to save ‘the Glad’. His great-grandmother lived in Lant Street, and according to family tradition his great-grandfather worked in the brewery across the road from the pub. Chris recognises that of course things change, old gives way to new, and it is impossible to preserve everything. But he adds that London is being plundered and pillaged and ‘meanwhile, local communities are dying’.

Chris and his family are far-flung now: none of them lives in Southwark, but they still meet up at the Gladstone because of the stories that link them to it. The family anecdotes handed down to children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren become over time part of the fabric of our nation, the tiny details in a great tapestry.

On his recent trip to the Far East, the Prime Minister vowed to do something — though who knows what and it’s far too late, anyway — about the foreign companies buying up swaths of London and its history. If only he could, because it’s awfully hard for communities to fight them and their untold wealth. The fight to save the Gladstone Arms is a small part of a much bigger fight: to save the life and soul of London, and to uphold values greater and more enduring than money.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Peter Oborne is an associate editor of The Spectator.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in