The conventional history of modern art was written on the busy Paris-New York axis, as if nowhere else existed. For a while, nowhere else did. People wondered, for example, whyever the mercurial Whistler volunteered for the unventilated backwaters of Britain. But London was eventually allowed into the international conversation following successful pop eruptions that began in the Fifties. Germany followed.

Now, perhaps as a response to a wired and borderless planet, where images can be instantaneously transmitted and sacred cows may be frivolously slaughtered, there is a revisionist and more inclusive policy for entrance to art’s pantheon. The braided cord has been lifted. Everyone can join the club.

New York’s Museum of Modern Art is showing an exhibition called Transmissions, which illuminates neglected art from Eastern Europe and Latin America. And the event of the season at London’s Tate Modern is The World Goes Pop, an account of pop art beyond SoHo lofts and Chelsea studios. An account, indeed, that even takes in Cluj-Napoca, Bogota and Wroclaw. To the established names Paolozzi, Warhol, Hamilton and Lichtenstein we must now add Corneliu Brudascu, Joan Rabascall and Bernard Rancillac.

The authorised version is that pop art was, circa 1956, the simultaneous creation of austerity-blighted London artists yearning for the glamour of America and New York artists responding ironically to a domestic culture of obsessive consumerism, wonderful sign-writing, overbearing advertising and occult sexualisation of everything from tinned beans to vacuum cleaners.

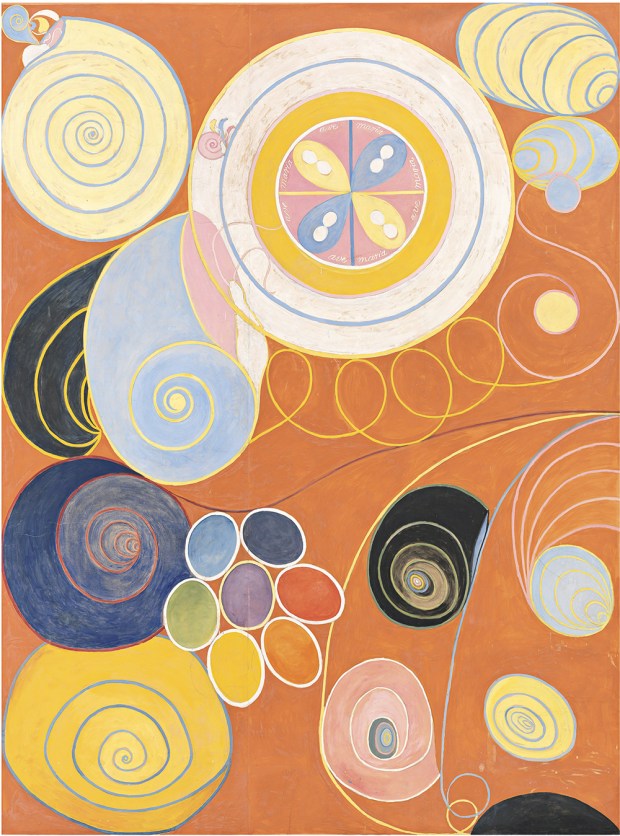

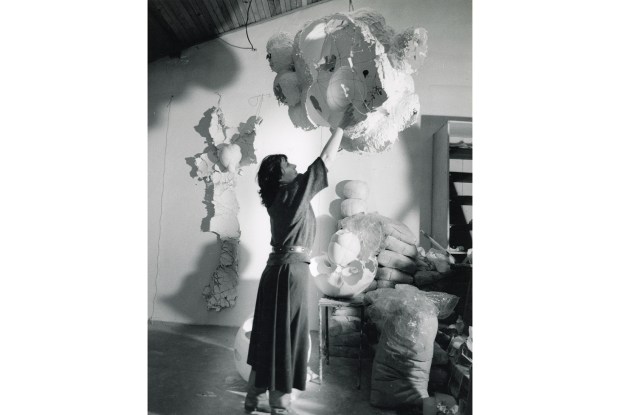

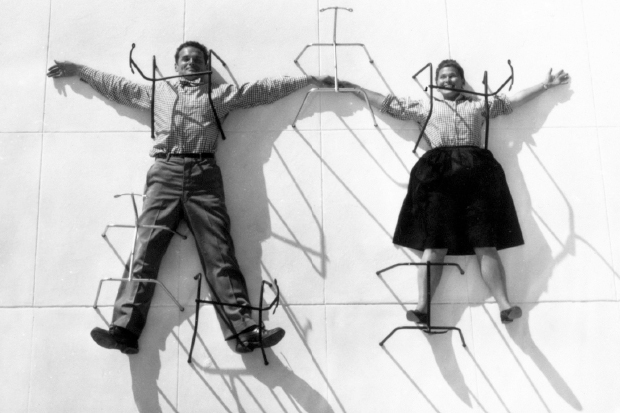

With visual puns very much intended, they used media techniques — screen printing, lithography, photomontage, irreverent sampling, flat colours, strident messages — to satirise and lionise the American Dream in their mass-produced art. What we can now see at Tate Modern is that these very same techniques and a similar interest in synoptic images were also at work for revolutionary movements in Colombia and anti-nuclear protestors in street-fighting Paris

There was, necessarily, a popular appeal in pop art and the new Tate show will replicate that, replication being the very essence of pop. It’s an exciting restatement of history, but there are big questions. Pop art’s infatuation with the media led to absurdities: weren’t the mass media actually more interesting than the art that exploited their techniques? Tom Wolfe asked this question in his brilliant essay ‘Chester Gould versus Roy Lichtenstein’, Gould being the original newspaper cartoonist who inspired the popster.

Wolfe, going to the source, preferred Gould. And if we look coldly at world pop, it is all second-rate. It would be absurd to criticise the Romanians and Colombians as derivative, since that’s the nature of the subject, but there’s not much true vitality here. This is emphasised by the drab installation in Tate Modern’s lifeless rooms. Never has a show needed or deserved more noise and light.

And there are two more points to make. One: expanding the definition of pop expands the market for it. Warhol and co. are now beyond the reach of even the very rich, so markets can be made in the newly validated Brudascu, Rabascall and Rancillac. Indeed, The World Goes Pop is sponsored by EY, a global financial-services group. Two: what we find in the show is not so much undiscovered genius as, wonderfully, the last moment when everyone agreed that art should be gloriously visual before tedious conceptualism became the inflexible convention that Paris-New York had once been.

During one of the recent well-publicised disappearances of the sometime conceptualist, people wore T-shirts asking ‘Where is Ai Weiwei?’ We now know the answer. A little less dissident than heretofore, Ai has been released into the global art community and can be found, sanctified, at the Royal Academy.

Ai has something of Jackson Pollock and Damien Hirst about him. Like Pollock, he is a curated phenomenon. Like Hirst, he has a genius for antics: handcrafting his own reputation is his favoured medium. Thus, Ai arrives at the RA fully accessorised with multimedia guides, DVDs, branded merchandise, books of quotes, drool by Obrist and other devotional texts. Thus we know much more about Ai than his art.

The Royal Academy is showing work completed since Ai’s return from New York to China in 1993. Some of it does not rise much above the level of a prank, or pseudo-event. Being photographed dropping a Han Dynasty vase, for example. And if a student showed me a CCTV camera carved in marble, I’d smile indulgently and think, ‘Try again, dear.’

But more substantial pieces have real poignancy and even beauty. The monumental ‘Trees’ in the courtyard are strikingly delightful and in ‘Souvenir from Shanghai’ (his old studio reassembled into a lump) or ‘Straight’ (an enormous arrangement of rods once used to reinforce concrete to memorialise the Sichuan earthquake) there is a sinister presence, dark wit and aesthetic sense going way beyond the sum of the rust and rubble of the parts.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in