No sooner had I stepped into the private view of Frank Auerbach’s exhibition at Tate Britain than I bumped into the painter himself. Auerbach was standing, surrounded by his pictures of 60 years ago, but he immediately started talking instead about Michelangelo. Of course, it is generally safe to assume that when artists talk about other artists they are also reflecting, at second hand, on their own work. And so it was in this case.

Michelangelo, Auerbach pointed out, had stingingly described someone else’s architectural design as looking like ‘a cage for crickets’. So, he argued, Michelangelo was clearly striving to make his own work the opposite of that: to give it grandeur.

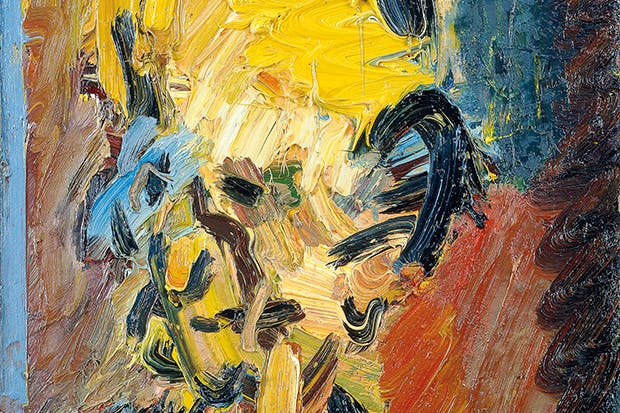

Now, in writing about Auerbach’s art, it is the intense laboriousness of his methods that are usually stressed: the way in which he has worked daily in his studio since the early 1950s, how for a long time he took just one day’s holiday per annum, spent on Brighton Pier, but eventually gave up that frivolity. Another frequent theme is the startling quantity of pigment he used in his early years — and understandably so, pictures such as ‘Head of E.O.W.’ (1961) have a greater thickness of impasto than almost any in art.

You have only to glance around the galleries at the Tate, however, to find majesty there too. ‘E.O.W., S.A.W. and J.J.W. in the Garden’ (1963), for example, has the presence and dignity of an ancient Egyptian sculpture. Except, of course, that it’s obviously a picture of a modern woman and a couple of children in a suburban backyard.

Auerbach’s work often combines those two qualities. On the one hand, there’s a geometric power that reduces a north London street scene such as ‘Looking Towards Mornington Crescent Station’ (1972–4) to a series of bold slashing and intersecting brush strokes. ‘Flag-like’ is a term he’s used to describe the result he tries to achieve.

On the other hand, this is palpably an everyday corner of Camden — a few streets of which have provided Auerbach with subject matter for half a century rather in the way that John Constable got one marvellous painting after another from a few hundred yards of the River Stour. As it happens, Constable is another predecessor about whom Auerbach has mused. He has described the way that, by depicting such things as rotten planks and slimy posts, Constable was ‘blatantly shoving rubbish into our faces’ but at the same time making ‘grand, Michelangelo-esque compositions’ from this riverbank detritus.

With an Auerbach painting, it’s not so much that rubbish is being shoved in your face, more that you are made hyper-aware of the texture and weight of what you are looking at. This is the task the paint performs, and it’s a sensation that is not transmitted well in photographs. Of course, it’s always true with good paintings that you can only judge them properly when you are standing in front of the original. But it’s doubly true with an Auerbach, because the surface and substance of the paint counts for so much.

Over decades, that astonishing early impasto slowly thinned; some recent pictures such ‘Hampstead Road, Summer Haze’ (2010) have a positively light, airy quality. All the way through, though, the paint does the same job, which is to make you sense the weight and presence of what you are looking at.

At first glance, or even second and third, an Auerbach can be hard to ‘read’. That is, it is difficult to decode what you are actually looking at. This difficulty comes from Auerbach’s effort to hit different targets simultaneously: intense realism and almost abstract grandeur, while conveying a sense of novelty as of something seen for the first time.

If you persist, though, the flurry of brush strokes and even — in the case of a ‘Studio with Figure on a Bed II’ (1966) — worms of pigment squeezed straight out of the tube usually begin to give a sense of real solid objects, ‘recalcitrant things’, as he once put it, that you might ‘bump into in the dark’.

This is an occasion for counting the years, 64 of them now, amounting to one of the great marathons in the history of art. The curator, Catherine Lampert, has been posing for the artist once a week since 1978, a remarkable record of fidelity in itself; she has done a beautiful job on this retrospective. Everything — the mid-grey wall colour, the sparse hang — feels just right.

Auerbach’s old friend Lucian Freud once remarked that ‘when one’s doing something concerned with quality, a whole lifetime doesn’t seem enough’. But, in this case, it has been sufficient. Auerbach has won his long tussle with paint and reality, again and again. With this exhibition, he joins the masters.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in