One day Julia Margaret Cameron was showing John Ruskin a portfolio of her photographic portraits. The critic grew more and more impatient until he came to a study of the scientist Sir John Herschel in which the subject’s hair stood up ‘like a halo of fireworks’. At this point, Ruskin slammed the portfolio shut and Cameron thumped him violently on the back, exclaiming, ‘John Ruskin, you are not worthy of photographs!’ He was indeed smackingly wrong to dismiss her work, as visitors to an exhibition at the V&A celebrating the 200th anniversary of her birth will be able to see for themselves.

There are multiple ironies underlying this spat (they happily made up by lunchtime). Ruskin disapproved — officially speaking, at least — of photography. Discoursing on the popular belief that ‘the camera cannot lie’, he remarked that photographs were true in a sense. ‘But this truth of mere transcript has nothing to do with Art properly so called; and will never supersede it.’

A complication is that Ruskin himself had collected hundreds of daguerreotypes of landscape and architectural subjects, often collaborating closely with the photographers who had taken them. Some of these very closely resembled his own watercolour drawings. There was a further paradox. In a way his complaint about Julia Margaret Cameron’s pictures was that they had too much to do with art, but not the variety he favoured.

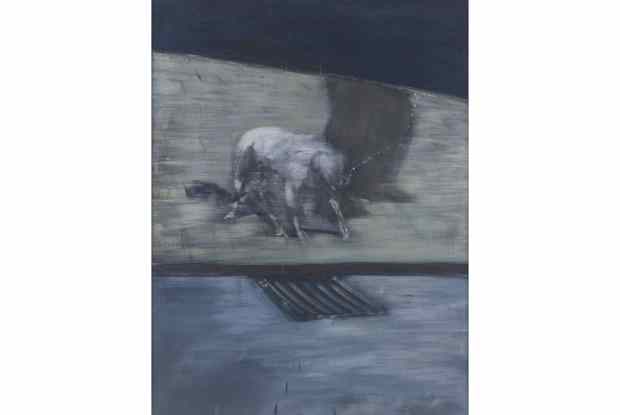

Ruskin admired the close-focus style of Pre-Raphaelites such as Millais — which was in turn heavily influenced by photography — and painted in that manner himself. Cameron, however, reflected an entirely different kind of painting. Dante Gabriel Rossetti — an astute observer if a bad speller — put his finger on just what that was when he thanked her for ‘the most beautiful photograph’ she had sent him, adding, ‘It is like a Lionardo.’

That was a bull’s eye. Cameron often consciously imitated High Renaissance painting, posing youthful friends and relations in the attitude of angels by Raphael or a Michelangelo sibyl. Years later, one of her models recalled, ‘No wonder those old photographs of us, leaning over the imaginary ramparts of heaven, look anxious and wistful; this was how we felt.’

The anxiety was created partly by Cameron’s commanding personality — ‘a terrifying elderly woman’, according to the same witness, ‘with plump eager face and piercing eyes’. It was also the product of the long exposures Cameron favoured (up to four minutes of motionlessness for the sitter). These, in turn, take us back to Leonardo because she — like the Italian master — understood the crucial importance of lighting.

All she required as a studio, Cameron wrote, was a room ‘capable of having all light excluded except one window’, and that she would drape with yellow calico. Exposure times were lengthy in the early days of photography, causing some practitioners to fix their sitters’ heads in clamps to prevent them moving. Restricting the illumination lengthened the duration even further. But in conjunction with Cameron’s tendency to take her pictures slightly out of focus this procedure created a wonderful softness. It was indeed the photographic equivalent to Leonardo’s sfumato, defined by the master himself as ‘without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke’.

Clearly, the works of Julia Margaret Cameron were not ‘true’ in the sense that Ruskin discussed. They were highly artificial and carefully constructed. That, however, is probably the case with any good picture, whether painted, drawn, photographed or filmed. There are deep interconnections between all those ways of making images of the world about us; this is the premise of a book on which I have been working with David Hockney, A History of Pictures, to be published next autumn.

We argue that there are continuities running from the images on the walls of prehistoric caves to the ones on your computer screen. In part, this is because all pictures share the same problems, arising from an attempt to represent a three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. It is also because images in different media have always influenced one another, and still do.

Photography was first revealed to the world in 1839 by a painter and impresario named Louis Daguerre. In fact, however, it had at least six progenitors: three French and three British. One of the British contingent was Julia Margaret Cameron’s model, Sir John Herschel, a brilliant chemist who came up with the ideal fixative. What all of them had in common was the ambition of capturing the images in a camera obscura in permanent form.

William Henry Fox Talbot recalled that he conceived that idea when thinking about ‘the inimitable beauty’ of the images he saw in a pre-photographic camera — ‘fairy pictures, creations of a moment and destined rapidly to fade away’. Thomas Wedgwood, son of the famous potter, had tried unsuccessfully to do the same thing in the 1790s.

This brings out a crucial point. Europeans were familiar with the images made by a camera for decades, indeed centuries, before 1839. In 1769 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, emphasising the candour of his Confessions, stressed that it was a ‘portrait, not a book’: ‘I shall be working, as it were, in a camera obscura,’ he added. ‘No art is needed beyond that of tracing exactly the features I see there.’ Clearly the notion that the camera could not lie predated photography by at least 70 years.

Even in the 18th century others disputed the idea that images revealed by a camera were inherently truthful — and, of course, they were right. Any good image is likely to have been staged, like Cameron’s portraits, more or less painstakingly. The way artists have done this will be the theme of an exhibition at Tate Modern next year, Performing for the Camera. Indeed, that phrase describes how many famous pictures have been taken.

Even among photographs purporting to be documentary snapshots of real life a surprising number turn out to have been prearranged. This is — very probably — true of Robert Capa’s ‘Falling Soldier’, which apparently captures the moment of death during the Spanish Civil War. Robert Doisneau’s romantic image of postwar Paris, ‘The Kiss’, was discovered — more than 40 years after it was taken — to have been posed by two young actors.

When such ‘faked’ photographs are unmasked, there is usually an outcry. Making them is considered an immoral act, even a sackable offence, in journalism. Perhaps we should relax; after all, no one makes a fuss about staging paintings. In this era of digital photography and Photoshop, most photographs have been more or less altered. As Hockney points out, there are numerous badly drawn photographs about. The border between the hand drawn and the photographic is utterly blurred; but then it always was.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Julia Margaret Cameron is at the V&A Museum until 21 February 2016.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in