This is a documentary in which three men travel across Europe together, but they’re not pleasurably interrailing, even though there are often times they probably wished they were. For two of them, Niklas and Horst, the journey is about confronting their fathers, who were high-ranking Nazi officials responsible for the deaths of millions of Jews, while for the third, the eminent British human-rights lawyer Philippe Sands, it means visiting the place where his grandfather’s family was exterminated. This place, Galicia, which straddles the modern-day border between Poland and Ukraine, is the exact place my own grandmother’s family were murdered. Her father lost every one of his seven siblings. She lost every aunt, uncle and cousin. And so I would wish to ask Niklas and Horst what Sands does ask Niklas and Horst: how do you feel about your father being this sort of man? It is a horribly gripping question, just as this is a horribly gripping film.

Sands was writing a book about international law, and its origins in the Nuremberg trials, when he first came across Niklas and Horst, who are now in their seventies. Niklas is the son of Hans Frank, who was governor-general of Nazi-occupied Poland, which came to include Galicia. He was known as ‘the butcher of Poland’. Horst is the son of Otto von Wächter, one of Hans’s deputies and governor of Krakow and then Galicia. Between 1939 (when both Niklas and Horst were born) and 1945, they were basically mass murdering by day and returning to their families in the evening. But while one son accepts what his father was, the other will not, and therein lies the riveting tension.

In a way, Niklas has it the most easy, as hating his father was never much of an effort. You suspect he’d have hated his father even if his father had only ever been a fishmonger. Hans was cold and cruel. Hans, for some years, even denied Niklas was his. Niklas has no problem condemning his father absolutely. ‘I despise him,’ he says. ‘He was a coward,’ he says. His father disgusts him so totally that, at all times, he carries a photograph of his dead body, taken moments after he was hanged at Nuremberg, ‘so I can see justice was done’.

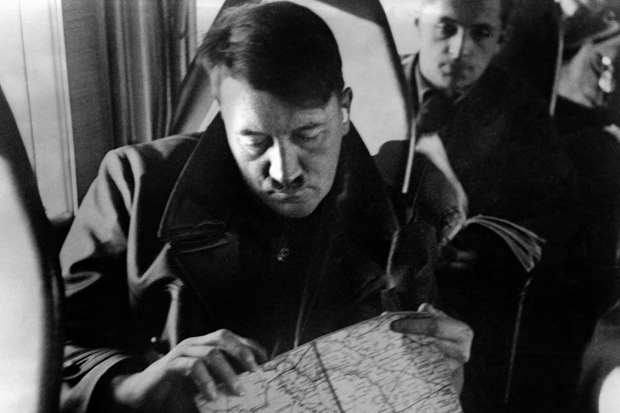

Horst? Horst is Austrian rather than German, which speaks volumes, as Austria has never faced up to the role it played. (Once went to Austria; it is quite creepy.) Horst had a good childhood. Horst shows Sands a photograph album and although Sands sees monsters on every page, including Hitler and Himmler, Horst sees only happy times. Horst does not deny the Holocaust, but refuses to believe that his father was directly involved. It was ‘the system’, he keeps saying, and ‘the system is something we today cannot imagine’.

They travel to childhood homes, to burned-out synagogues, and finally to Lviv, formerly in Galicia, now in Ukraine. This is where, on 25 March 1943, under the instruction of Frank and von Wächter, 4,000 Jews were rounded up from the ghetto, marched into the woods, and shot by the Gestapo. Their bodies are still in the ground. This is where the family of Sands’s grandfather lies, and the family of my grandmother too. ‘You’re not responsible,’ says Sands, ‘but your father signed off on this.’ ‘My father wouldn’t have,’ says Horst. Niklas says, angrily, ‘Your father was involved in this terrible crime in this terrible place. Accept it.’ Horst just stands there, tearing at a flower in his hand.

There are no Act of Killing-style breakdowns, despite Sands’s best efforts. He brandishes paperwork. He loses his temper. He challenges Horst, who is otherwise genial (irritatingly), to the point where it feels like bullying. As Horst was too young ever to be complicit, why is it important that he owns up to his father’s criminality? There is one scene that answers that. The Nazis are still revered in the Galician part of Ukraine, because they took up arms against Russia. There is even an annual celebration of the Waffen-SS Galizien Division, where attendees dress up in SS uniforms, complete with swastikas. The three are filmed at this event, where Horst, once his identity is disclosed, is treated as a hero. ‘Your father,’ he is even told, by someone with his arm round him, ‘was a decent man.’ Horst beams. Horst, for the first time, looks so proud. And that’s why it matters, I suppose.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in